05/01/1995

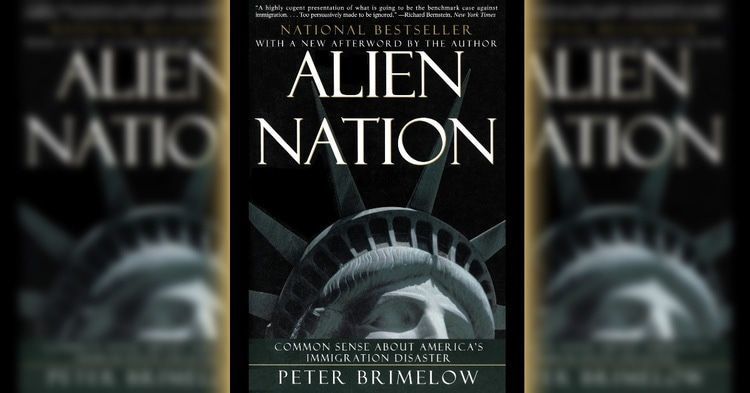

Alien Nation: Common Sense About America’s Immigration Disaster. (book reviews)

Nathan Glazer

National Review, May 1, 1995 v47 n8 p78(3)

© National Review Inc. 1995

THE ENGLISH, it is well known, are often direct and even rude in their disagreements, where Americans are circumlocuitous and fearful of giving offense. I hope that the English national characteristic will be ignored in discussions of Peter Brimelow’s important book, without any confidence that it will be. I will put style and manner aside and go directly to the argument.

Mr.Brimelow argues that our immigration policy is a disaster. He believes that there are far too many immigrants being admitted when considered from the point of view of national interest, however defined, and that their costs to public budgets exceed their contribution in taxes. Culturally, they are leading to the dissolution of a distinctive and European-based nation. Politically, he asserts, the number and the ethnic and racial character of the new immigration do not reflect the preferences of the American people. Had the people been asked, and had the implications of the 1965 immigration reform been set before them, they would never have approved. Further, our current wave of immigration, coming into the country at a time when any strong measure toward ''Americanizing'' immigrants is undermined by prevalent attitudes among American educators and opinion-forming groups, may lead to a terrible divisiveness.

Many of the facts about current immigration given in this book will be surprising even to well-informed readers. Some may not be facts at all. (Is it really the case that many of those being admitted under the act permitting Amerasian children from Vietnam to immigrate with their families were born more than nine months after the last American soldiers left Vietnam?) On the whole, though, I think they will stand up.

I have no basic argument with Brimelow’s analysis of the economic consequences of current immigration. He believes they are minor, neither negative enough to require action to reduce immigration for economic reasons alone, nor positive enough to indicate that the present level of immigration should be maintained. He believes the value of immigrants to the American economy, whatever it may have been, is declining, as the average level of education and work skills of immigrants falls over time.

There is one aspect of the economic argument to which he gives very little attention, though he does refer to it: What is the effect of immigration on American blacks, the worst off of Americans (except perhaps for Puerto Ricans)? In a book-length analysis, this should have received more attention. I think one reason he spends so little time on this issue is that he makes so much of the white and European ethnic and racial character of the American nation. He is therefore at a loss as to how to make his argument if he gives full weight to the fact that at its Founding the nation was 20 per cent black, and it is now 12 per cent and modestly rising. Even if we were not multicultural in outlook at our birth, we were already multiracial. If indeed we are at risk of losing our unifying European racial and cultural character because of the non-European character of current immigration, what does one make of this inconvenient reality? If the issue is race, the game was lost at the beginning. If the issue is culture, matters are somewhat different, but Brimelow, to the credit of his English directness, does not want to give up race as an aspect of national culture. If the racial character changes, he believes, the culture changes. I disagree. I do not see how the fact that 20 per cent or more of the students at our elite colleges and universities are now Asian will change our national culture. How much did it change when the number of Jews entering such institutions rose to 20 per cent or more?

Confusing his argument is the amalgam "non-European,'' as well as the amalgam "immigrants.'' Brimelow is well aware that immigration is polarized between those newcomers, mostly from Latin America and the Caribbean, with less education and work skills than the American ''average,'' and those, mostly from Asia, with more education than the American average. All these groups are non-European, except that Latin Americans are closer to being European and white than are Asians. If the issue is capacity to add to the American economy, why does Brimelow’s discussion concentrate on immigrants in general, and harp on their overall non-Europeanness? If the issue is the political assimilation of immigrants, one should hear more of the fact that the Asians naturalize much faster than the Latin Americans. (Brimelow charmingly points out — he does often poke fun at himself — that the English are least likely to naturalize.) If the issue is assimilation to American culture, we should hear more about differences in the knowledge of English and the speed with which English is taken up.

Brimelow insists on bringing together race and culture, but the linkage makes problems for his thesis. He should be insisting not that America’s immigration policy in general is a disaster, but rather that we should favor the better-educated and English- speaking immigrants, as Canada does, and if this means many more Asian immigrants, and fewer Latin American and Caribbean ones, so be it. That is where the logic of his argument points. But that is not the way the argument reads: Brimelow will be read as saying, and indeed he does say, that there are just too many immigrants because of their race and capacities, period. That is not what the finer print of his case adds up to, however. If we take that fine print seriously, we might guess he would be content simply to halve immigration, cutting off the lower half as measured by education and work skills, which would mean many fewer Latin Americans.

When he comes to his specific recommendations, there is a lot of good sense: Knowing English should be considered a plus in terms of eligibility for immigration. We should eliminate automatic citizenship for the children of illegal immigrants. (Peter Schuck proposed this years ago.) The Hispanic category in the census and in public policy should be eliminated. (It encourages a false amalgam. There are Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, Cubans, Dominicans, Nicaraguans, Salvadorans; but to create a category ready-made to exaggerate distinctive grievances, as we have done, is idiotic.) Of course immigrants should be excluded from affirmative action. (It was intended for native minorities, not those who have come willingly because they hoped life here would be better than life where they came from.) Brimelow also believes the borders can be properly policed. I am not sure he is right, but we should try harder.

Yet it is too late for this country to consist of a single race bound to a common culture. I think the new immigrants in the end will be as American as the Indians and West Indians of England will be English, as the Algerians of France will be French, as the Turks of Germany will be German. There will be problems, of course. I doubt, though, that they will match in seriousness a problem that has nothing to do with current immigration: the state and status of black Americans.