By Steve Sailer

01/31/2011

January 2011, has been a month of great divisiveness. Yet one individual has unified America: Amy Chua.

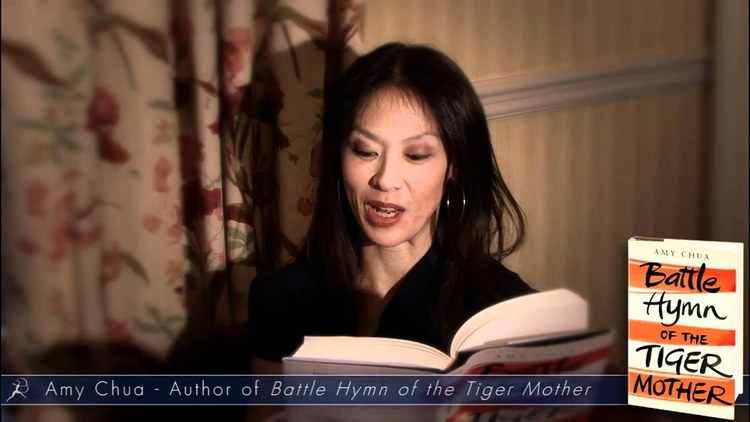

For the last few weeks, it has sometimes seemed as if everybody hated (and/or envied) the Yale Law School professor whose third book, Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother, recounts the hyperambitious "Chinese mothering" she used to nag her two daughters into being straight A students and classical music prodigies.

For example, Chua writes that her daughter can remember:

"… three things I actually said to her at the piano as I supervised her practicing:

1. "Oh my God, you're just getting worse and worse."

2. "I’m going to count to three, then I want musicality."

3. "If the next time’s not PERFECT, I’m going to TAKE ALL YOUR STUFFED ANIMALS AND BURN THEM!"

Ever since an excerpt was published in the Wall Street Journal under the title Why Chinese Mothers Are Superior January 8, 2011, the public can’t get enough of the mom they love to hate. She’s even been a superstar at Davos last week, among the global uberclass.

Indeed, President Obama’s State of the Union address, with its obsessing over Chinese competition, had the subtext that Americans must finally come together and unite against the Amy Chua Menace.

Yet, remarkably little attention has been devoted to the big picture: how Chua’s new memoir relates to her first book, World on Fire: How Exporting Free Market Democracy Breeds Ethnic Hatred and Global Instability, which I reviewed here in VDARE.com exactly eight years ago.

Before I get to the deepthink part of my review of Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother, let me cover a couple of issues.

As Charles Murray was the first to point out (and most people still haven’t noticed), Chua can be an (intentionally) hilarious writer. I read Tiger Mother in about four hours and laughed out loud for maybe half of the time.

Chua isn’t just telling you exactly how she feels: she’s also playing a character who is funny because you know she’s going to tell you exactly how she feels. When satirist Evelyn Waugh tottered around mid-century London with a giant Victorian ear trumpet clamped to his head (which, when a postprandial oration began to bore him, he would ostentatiously unstrap and set on the table), he wasn’t just expressing his reactionary curmudgeonlyness. He was also gleefully playing his chosen role as England’s leading curmudgeonly reactionary.

Similarly, Chua works hard in her writing to make herself the face of an increasingly important type: the flamboyantly Asian mother who forces her children to practice piano or violin endlessly to look good a decade from now on their Ivy League applications.

For instance, she commiserates with her prize-winning pianist daughter about how American pop culture doesn’t validate her child’s Oriental docility:

"In Disney movies, the 'good daughter' always has to have a breakdown and realize that life is not all about following rules and winning prizes, and then takes off her clothes and runs into the ocean … But that’s just Disney’s way of appealing to all the people who never win any prizes. …

Chua, who is her own best audience, observes:

"I was deeply moved by my oration."

When her higher-testosterone younger daughter wants to drop violin for tennis, Chua recounts:

"I compared her to Amy Jiang, Amy Wang, Amy Liu, and Harvard Wong — all first-generation Asian kids — none of whom ever talked back to their parents. … I told her I was thinking of adopting a third child from China, one who would practice when I told her to, and maybe even play the cello in addition to the violin and piano."

This looks artless, but notice how amusing the Sino-American names sound when read out loud in that precise order in a tone of mounting hysteria: Amy Jiang, Amy Wang, Amy Liu, and Harvard Wong. Or consider how much the author gets our hopes up momentarily that she might just be crazy enough to carry out her threatened adoption experiment. Wouldn’t you like to know how that would turn out?

Granted, Chua’s character in Tiger Mom isn’t original. Many East Asian women feel as Chua does about all the politically correct rationalizations that whites tell each other to make America’s status climbing / mating market games seem less Darwinian. To Chua, happy talk is for losers. If you tell too many genteel lies, your children might start believing them. And then your descendants will be weak.

And you know what happens to the weak …

Chua’s semi-self-parody is an up-market version of the brilliant British comedienne Tracey Ullman's character Mrs. Noh Nang Ning, the brutally frank donut shop owner. Here’s a video from HBO’s 1990s sketch comedy show Tracey Takes On of Mrs. N coaching her nine-year-old niece at the figure skating rink:

Nice white mom [sententiously]: "Well, we don’t care about Henie winning … The important thing is that my daughter go out there and have a good time."

Mrs. Noh Nang Ning [fiercely]: "Me, too. I want niece to have good time. You know what good time is? Winning! …"

Mrs. Noh Nang Ning [encouraging her niece]: "You lose, you no come home!"

Nice white mom [aghast]: "How can you SAY that to a child?"

Mrs. Noh Nang Ning [dismissively]: "Good motivation. Kid no want to sleep in box on street. … You don’t win, you nothing!"

Chua frets:

"The next generation [i.e., her daughters' children] is the one I spend nights lying awake worrying about. … Finally and most problematically, they will feel that they have individual rights guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution and therefore be much more likely to disobey their parents and ignore career advice. In short, all factors point to this generation being headed straight for decline.

"Well, not on my watch."

Chua shares happy family memories:

"One jarring thing that many Chinese people do is openly compare their children. I never thought this was so bad when I was growing up because … my Dragon Lady grandmother … egregiously favored me over all my sisters. 'Look how flat that one’s nose is,' she would cackle at family gatherings, pointing at one of my siblings. 'Not like Amy, who has a fine, high-bridged nose. … That one takes after her mother’s side of the family and looks like a monkey.'"

By the way, her hugely creative father is only a minor, dissonant character in her book. She mentions toward the end that he wound up loathing his Dragon Lady mother for her Chinese mothering.

So much for Chua’s humor. Secondly, what I’m sure you are all dying to know: What’s my opinion of Chua’s childrearing techniques?

Like both Prof. Chua and many of her detractors, I myself don’t have a large enough sample size of children reared to generalize wildly from my own personal experiences. Unlike both, however, I’m rather humbled by my ignorance. So, I’m going to skip the advice-giving (other than to say that you should never write a memoir featuring your children as major characters, especially if you have more than one.)

Malcolm Gladwell, David Brooks, and a host of other sages have explained that differences in natural ability are largely irrelevant to success. The only thing that really matters is having your child put in 10,000 hours of focused practice.

Well, Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother shows you what The 10,000 Hour Rule looks like in the real world. It’s not a pretty sight.

As an obvious aside, let me point out that Chua’s two high-achieving daughters chose their ancestors wisely. Amy Chua’s paternal grandmother got rich opening factories in the Philippines. Her father, Leon Chua, Professor of Electrical Engineering at UC Berkeley, inventor of Chua’s Circuit and the concept of the memristor (Hewlett-Packard is currently gearing up for mass production of them, four decades after he dreamed them up) has received nine honorary doctorates. Her mother, a chemical engineering major, was valedictorian of her college class in Manila. The author herself holds an endowed chair at the nation’s most intellectually elite law school, Yale.

So does her husband, Jed Rubenfeld. (They met when they were on the Harvard Law Review.) In his spare time, Jed wrote a 2006 murder mystery novel, The Interpretation of Murder (in which

Sigmund Freud plays detective

You would expect less regression toward the mean in the offspring of family trees with these levels of IQ, energy, and Attention Surplus Disorder. (As Ms. Chua notes, "As a purely mathematical fact, people who sleep less, live more.")

Chua notes that her Chinese-Jewish-American children represent "an ethnic group that may sound exotic but actually forms a majority in certain circles, especially in university towns." It would be interesting to try to quantify how much of the rage against Chua in the women’s' press is motivated by inchoate feelings that Chinese women, with their naturally straight hair, are Stealing Our Men. (Before going to Harvard Law School, Chua’s handsome husband studied drama at Julliard alongside Val Kilmer.)

Chua likes to portray herself as the stereotypical Chinese, diligent, conventional, and uncreative:

"As the eldest daughter of Chinese immigrants, I don’t have time to improvise or make up my own rules. I have a family name to uphold, aging parents to make proud. I like clear goals, and clear ways of measuring success."

Chua sounds like the last person to become controversial:

"I did well at [Harvard] law school, by working psychotically hard. … But I always worried that law really wasn’t my calling. I didn’t care about the rights of criminals … I also wasn’t naturally skeptical and questioning; I just wanted to write down everything the professor said and memorize it."

Yet you don’t have to be extremely creative to make important contributions to public understanding — as long as you have the courage to tell truths that other people won’t. At the end, Chua rants to her daughters:

"All these Western parents with the same party line about what’s good for children and what’s notI’m not sure they are making choices at all. They just do what everyone else does. They're not questioning anything, either, which is what Westerners are supposed to be so good at doing. They just keep repeating things like 'You have to give your children the freedom to pursue their passion,' when it’s obvious that the 'passion' is just going to turn out to be Facebook for ten hours …"

Chua deals with the kind of subjects that everybody thinks about, but we're not supposed to talk about. For example, Chua’s 2003 book World on Fire was the first to acquaint me with one of the key facts of the history of the 1990s. Chua wrote:

"IN THE spring of 2000, a professor whom I'll call Jerry White was furiously trying to finish an article on the debacle of Russian privatization. … It seemed to me that most of the key players in the privatization of Russia were Jewish.

"'Oh, no,' Jerry replied instantly. 'I don’t think so.'

"'Are you sure?' I pressed him. 'If you look at their names … '

"'You can’t tell anything from names,' Jerry snapped, clearly not wanting to discuss the topic any further.

"As it turns out, six out of seven of Russia’s wealthiest and, at least until recently, most powerful oligarchs are Jewish."

Google News finds 1,570 recent news articles about "Amy Chua". Yet only two of those go on to mention the crucial term she coined in World on Fire — "market-dominant minorities" — to describe groups like her own Overseas Chinese and Ashkenazis in Yeltsin’s Russia.

You may think I’m just dragging the topic of the day around to my own area of interest, but Chua explains in her new memoir the origin of her first book:

"Combining my law degree with my own family’s background, I would write about law and ethnicity in the developing world. Ethnicity was my favorite thing to talk about anyway".

Chua’s ancestors were from southeastern China’s Fujian province "which is famous for producing scholars and scientists". Traditionally, Fujianese led in the mandarin civil service exams and today in China’s college admission test.

Chua’s parents grew up in the Philippines, where a small number of Chinese own most of that country’s business assets. The population of the Philippines has grown from 28 million a half century ago to 92 million in 2009, so there’s not all that much to go around.

In Southeast Asia, the Chinese have most of the money, but the natives have most of the guns. So, when Chua’s aunt in Manila was murdered by her Filipino chauffeur who then fled, the Filipino policemen made only derisory efforts to find and arrest their co-ethnic. Sure, he’s a murderer, the Filipino cops seem to have reasoned, but he’s our murderer. And that rich Chinese woman probably had it coming.

Nice place …

Chua’s rich family comes from a poor world where there’s room for only a few at the top to live well. They do what it takes to stay on top. She has inherited these worries:

"One of my greatest fears is family decline. There’s an old Chinese saying that 'prosperity can never last for three generations.'"

Of course, 19th Century Americans had a similar saying a century ago: From shirtsleeves to shirtsleeves in three generations.

Yet this American version never had quite such a Malthusian ring to it. If a 19th Century American family fell out of riches, they weren’t in danger of Oriental poverty. They were still a 19th Century American family — with a giant new country to try their luck in.

Why has life in America generally been less stressed-out than in other parts of the world?

America has traditionally been a lot nicer place than China or the Philippines. We Americans like to dream up self-congratulatory reasons for this. Some of them might even be true. But a big reason is simply that America is less crowded — and thus less competitive.

Back in 1751, the highest achiever of all Americans, Benjamin Franklin, explained the greater happiness of life in America: because a middle-class life is more affordable for the average person in empty America than elsewhere.

Unfortunately, our elites have been working to erase that distinction.

This is a content archive of VDARE.com, which Letitia James forced off of the Internet using lawfare.