09/19/2019

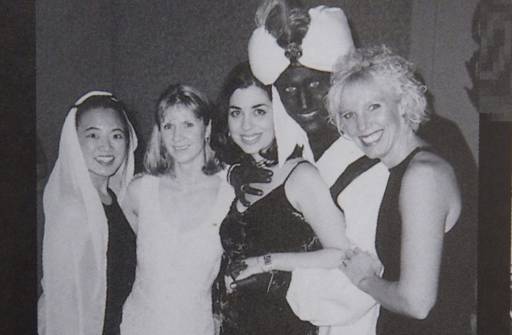

Maxime Bernier, leader of Canada’s insurgent immigration patriot People’s Party, summarized Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s clown-world blackface scandal [Justin Trudeau speaks after racist photo, by Veronica Rocha and Meg Wagner, CNN, September 19, 2019] with notable fairness:

I’m not going to accuse @JustinTrudeau of being a racist.

But he’s the master of identity politics and the Libs just spent months accusing everyone of being white supremacists.

He definitely is the biggest hypocrite in the country.

— Maxime Bernier (@MaximeBernier) September 19, 2019

Polls as of September 19 suggest Trudeau’s Liberal Party may not now win a majority in the October 21 federal election. Whatever happens, it’s a useful reminder that Canadian politics are not as stable as may appear. Immigration may be the next shoe to drop.

The conventional wisdom has been that Canada will avoid the populist disruptions that have arisen in other Western democracies. [Andrew Coyne: Why you shouldn’t expect to see populism take root in Canada, National Post, July 24, 2019] I can’t say I agree. Populism has always been a pillar of Canadian politics, especially in Western Canada, and even our socialist New Democratic Party began as a populist movement in the Prairies.

But something has changed. The electorate has been polarized before on such matters as patriating the constitution, North American free trade, the independence of Quebec, and (more historically) conscription during the two World Wars. It could be argued that these problems were overcome because the Canadian public was largely in agreement on social and cultural questions. This isn’t true any longer. The Canadian electorate is more polarized on cultural issues than ever before.

Canadian-born political scientist Eric Kaufmann, author of Whiteshift: Populism, Immigration, and the Future of White Majorities, has analyzed the change, drawing attention to the recent election of anti-elitist, populist parties in Canada’s two largest provinces (= U.S. states). In Ontario, the government of Progressive Conservative Doug Ford is more anti-elitist than properly populist. The government of Quebec led by the Coalition pour l’avenir du Québec (CAQ) is far more openly aggressive on the question of French-Canadian identity. The CAQ recently forbade all civil servants from wearing religious clothing, such as the burqa and niqab. [Quebec bans religious symbols for state workers in new law, Global News, June 16, 2019] A similar ban in English-speaking Canada would probably also be popular, but it’s unlikely than any provincial government would dare enact one currently.

And these small stirrings of revolt may be mild in comparison with a real populist movement at the national, federal level: Maxime Bernier’s People’s Party.

Maxime Bernier is a bilingual Francophone (Canspeak for French mother-tongue) politician from the majority-French province of Quebec. He held several Cabinet posts in the Conservative government of Prime Minister Stephen Harper, but was done in by a scandal involving secret NATO documents that he left at the house of his girlfriend, Julie Couillard, whose ties to mobsters and the Quebec branch of the Hell’s Angels had been a source of constant embarrassment. Prime Minister Harper gave up and sacked Bernier when Couillard gave a salacious tell-all interview about her nefarious ex-lovers, one of whom had been

murdered by gangsters. It was as good as a Canadian sex scandal can get. [Two boobs and a scandal, by Margaret Wente, Toronto Globe and Mail, May 29, 2008]

But Bernier resurfaced as a serious contender for the leadership of the Conservative Party after Stephen Harper’s 2015 election loss to Justin Trudeau. Bernier ran on a libertarian platform. He promised to end corporate welfare, abolish capital gains taxes, safeguard freedom of speech, and so forth. Despite his strange career and his heavily accented English, he had a certain charisma. In an appeal to a more right-wing and populist constituency in western Canada, Bernier asked his fellow Tories to think of him “as an Albertan from Quebec.” He touted an almost Reaganite economic vision of lower taxes, entrepreneurism, and social libertarianism — heresy to Canada’s social democrat Ruling Class.

Things seemed to go well at first. Bernier defeated nearly all other candidates and even received the eventual endorsement of reality TV-star and entrepreneur Kevin O'Leary. O'Leary, who himself was a candidate, is a sort of Canadian answer to Donald Trump, with a similar flair for the headline and the soundbite.

But Bernier’s bid for the leadership of the Tory Party was ruined by his refusal to endorse Supply Management — a peculiarly Canadian policy, effectively a government-sanctioned cartel protected by high tariffs, that permits dairy, poultry, and egg farmers to limit the supply of their products in order to ensure stable, but artificially high, prices. [How Canada’s supply management system works, CBC, June 16, 2018] His rival leadership candidate Andrew Scheer took the opposite position, endorsing Supply Management. Some claim that the intervention of the powerful but mysterious Dairy Lobby assured Scheer’s narrow victory. Bernier left the Conservatives and founded the People’s Party.

The People’s Party platform is supposed to be similar in principle to that of Bernier’s earlier leadership campaign, but the name suggests a populist twist on radical free-market principles which many voters may find incoherent. I for one cannot reconcile deference to big business, and its insatiable demand for more immigration, with Bernier’s newly emergent desire to lower immigration levels.

Bernier would like to think of his ideas on immigration as a radical departure from Canadian norms. [Maxime Bernier taps into immigration controversy as he launches People’s Party of Canada, by Daniel Leblanc and Laura Stone, Toronto Globe And Mail, September 14, 2018] But this is not really true. The Trudeau Liberals’ bizarre goal of increasing immigration levels to nearly half a million a year — equivalent to 4.4 million a year in U.S. terms — is very remote from popular opinion and common sense. But Bernier began by proposing only a very modest cap at 250,000. That number is not only exactly as it was under the Harper government, but also where it has been for the past thirty years or so. The Trudeau regime had increased the number to about 300,000, so Bernier’s original proposal would not make a significant difference. He has since announced a lower cap at 150,000. [Maxime Bernier says his party would cap immigration levels at 150K, by Salimah Shivji, CBC News, July 24, 2019] But even this annual number is larger than most Canadian cities outside the big metropolitan areas.

Bernier’s criticism of official “multiculturalism” is perhaps even more important. The People’s Party platform asserts that "immigration must not be used as a tool to forcibly change the cultural character and social fabric of Canada." This is a direct, and long-overdue, attack on the Liberal theory of the post-national Canadian state without a “core identity.” [Trudeau says Canada has no ‘core identity’, by Candice Malcolm, Toronto Sun, September 14, 2016]

Predictably, Bernier’s mild deviationism has elicited paroxysms of outrage from the cabal of journalists, civil servants, and politicians who form Canada’s governing elite. Left-leaning publications such as the Toronto Star, have decided that criticism of multiculturalism has attracted the Alt-Right bogeyman and that swarms of nationalists have finally found their moment to emerge from hiding. [Maxime Bernier’s alt-right problem, . by Zachary Kamel, Martin Patriquin, and Alheli Picazo, February 8, 2019] As usual, some Conservatives echo this hysteria for fear of being on the wrong side of an elite consensus.

But this isn’t to say that Canadians aren’t ready for Bernier’s more skeptical message on immigration. A 2018 study by the Angus Reid Institute showed that the slow and steady rise in immigration levels over the past few decades is correlated with rising criticism of immigration. [Immigration in Canada: Does recent change in forty year opinion trend signal a blip or a breaking point?, August 21, 2018] Half of all Canadians want levels to go down, and only about 6% want an increase.

It can’t be much longer until a political party campaigns, and wins, on a promise of significantly lowering immigration levels.

Support for Justin Trudeau’s Liberals was already weakening amidst an ethics scandal, superficiality, diplomatic failure, and allegations of undermining the independence of the judiciary and obstruction of justice. And Canada’s Leftist vote is fragmented amongst the Green Party, the socialist New Democrats, and the Liberals.

But I’m afraid Bernier won’t be the man to capitalize on this. His new party has been polling between 1-4%. This is not as bad as it appears — Canada’s two major parties both poll only in the mid-30s, and the Leftist Francophone nationalist Bloc Québécois is polling only at 4.5% yet currently has 10 seats in the 338-member House of Commons. But the BQ’s support is concentrated in Quebec. The People’s Party support is dissipated across all of Canada. Still, Bernier may hold his own riding (=district) of Beauce (which happens to be the whitest in Canada, at 99.3%).

Bernier may yet turn out to be Canada’s Nigel Farage — the populist, Euroskeptic firebrand who broke away from Prime Minister John Major’s Conservatives after the signing of the Maastricht Treaty in 1992. Farage founded the UK Independence Party in 1993. It took him 23 years to win the Brexit referendum in 2016. But he got his way in the end, and Farage-style Euroskepticism is now the dominant force in British Conservatism.

Anti-elitist populism and skepticism about immigration are already more advanced in Canada than Brexit was in the 1990s. It’s only a matter of time before either the People’s Party wins — or Canada’s entire right-of-center movement adopts Bernier’s ideas.

Aurelius Victor is one of 36.72 million Canadians … as of today.