09/01/2016

The Alt-Right breakout. Back in the States, the big news in August was the Alt-Right breakout. A picture tells a thousand words: blogger Audacious Epigone has the picture.

This is nothing but good news. Establishment strategy for years has been to silence the Alt-Right, to seal off any outlets through which our ideas might leak out into the public square.

For example: once upon a time Jared Taylor used to appear on radio and TV, and give talks at colleges. His American Renaissance conferences were broadcast on C-SPAN!

The guardians of our state ideology weren’t going to put up with that. They methodically sealed off all those outlets. (While at the same time striving to destroy Jared’s private career, which has nothing to do with American Renaissance or the Alt-Right.)

Yet now suddenly Jared’s being interviewed (albeit briefly and incompetently) by ABC News, and even showing up in a TV campaign ad for Mrs Clinton.

This must be wormwood and gall to Mark Potok and Heidi Beirich, chief ideological enforcers over at the Southern Poverty Law Center [ker-ching!] All those years of labor sealing off every tiny crack and fissure, and suddenly the dam has sprung a leak!

I can hear their teeth grinding — a sweet, sweet sound.

The godless Alt-Right. An interesting not-much-remarked feature of the Alt-Right, distinguishing it from the traditional American Right, is its godlessness. The Nine Theses of Alt-Right heresy posted at imgur.com (hat tip there to the Chateau) don’t even mention religion, except obliquely, in reference to "Cultural Diversity" (Thesis 6).

Most of the big Alt-Right names have dined chez Derb at one time or other. They all showed the same amused surprise at the fact that we say grace before meals. (I have to explain that it’s just a family custom we started when the kids were little, and we never felt like dropping it.)

Some of this irreligious tendency is just the slow slide away from organized Christianity among all sections of society, described with astounding prescience in the religion chapter of We Are Doomed (Chapter 8), and the frequent subject of news reports about the spiritual life of Americans.

There is a selection factor at work, too, though. Any individual human being is more or less inclined to religious styles of thought and behavior. In the Western world today, those more inclined might of course attach themselves to traditional Christianity; or they might turn to ideology.

As has often been noted, state ideologies, like the Cultural Marxism that currently holds sway in the West, key to the same social and psychological receptors as religions. Recall the late Larry Auster’s observation that blacks are sacred objects, criticism of which is received just as blasphemy used to be in the Age of Faith, and still is in places like Pakistan.

Alt-Right types — all of them, though in many different ways — are reacting against this state ideology.

What characterizes the Alt-Right is the rejection of Cultural Marxism; but while it characterizes us, it doesn’t unify us. That’s because we haven’t fled from the CultMarx pseudo-religion to some other, unifying faith. We don’t do faith.

Some people of course have done that, but they're not Alt-Rightists. They are the dwindling rump of the old Religious Right, holding prayer vigils outside abortion clinics and such.

Alt-Rightists can’t swallow the CultMarx ideology, and we can’t swallow traditional religion, either. So an invisible sky spirit came down to Earth and impregnated a human female? This happened at some actual moment in time, at some actual place, you say? Sorry, no offense, but no sale.

The Alt-Right is populated by people whose religious impulses are feeble or nonexistent. That’s exactly why we can’t swallow CultMarx!

It’s also why there is a strong mood of empiricism, of openness to science, among the Alt-Right. We are strongly disposed to believe our own lying eyes, and the properly replicated, reviewed work of careful scientists, over the ukases of some authority figure or the social consensus. That’s why we're race realists. The little lad in Hans Christian Andersen’s story "The Emperor’s New Clothes" grew up to be an Alt-Rightist.

I’m pretty sure about all that, but it leaves a question hanging in the air: Why aren’t there more Alt-Right scientists?

My best guess is that most working scientists are dependent to some degree on the Academy, where CultMarx is ferociously enforced. I’m open to other explanations, though, or to arguments that my entire thesis here is wrong.

What happened to Intelligent Design? Speaking of science and religion, as I just did in considering the Alt Righters, whatever happened to Intelligent Design? A dozen or so years ago we were all talking about it, and my mailbox was full with readers urging me to reconsider my attitude to Irreducible Complexity or the Cambrian explosion.

Now, nothing. The Discovery Institute is still in business, I see; and to judge by their website, they are quite active. Is anyone much listening, though? Fifteen years ago a lot of people were, and DI personnel were getting air time on cable TV. Now, to judge from the website, they are just talking to themselves.

On the other side of what was once a lively public debate, the TalkOrigins website, set up in 1996 to counter Creationist and Intelligent Design arguments, is still online with all its archived material, but looks not to have been maintained for a while. Clicking on the "What’s New" link gets you a 404. The latest entry under the "Post of the Month" link is for November 2014 (just a few months after my last column on ID). The site has, as the techies say, quiesced.

It looks to me as though the Kitzmiller decision of December 2005 killed off public interest. Or perhaps, since nobody’s mind was being changed, we just got bored with the issue.

Whatever, it’s a shame. As I said in that 2014 piece: "There are important gaps in our understanding of the world that ID, if it didn’t waste its time on far-fetched critiques of well-settled scientific topics, might have something to say about."

These thoughts followed my Great Courses lectures for the month of August: Prof. Gregory’s Darwinian Revolution.

I was a bit wary about buying the course, having noted that as well as postgraduate degrees in History of Science, Prof. Gregory is also a Bachelor of Divinity. In the event, I enjoyed it, and learned a lot about 18th- and 19th-century views on the origin of species. Prof. Gregory does, though, cut ID a bit too much slack for my taste. If you buy the course, buy it for the history, not the metaphysics.

Academic timidity. One depressing thing about the college campus idiocies that have been so much in the news this past couple of years, and that are being logged by websites like Campus Reform and Heterodox Academy, is the failure of academics to offer much resistance.

When students clamor to have separate bathrooms for black lesbian Muslims, or whatever the cause du jour is, why don’t their professors show up in force and tell them to get the hell back to their classrooms, or leave the campus? The reason is I suppose ultimately financial, but it speaks poorly of the courage of the average academic.

I suppose one shouldn’t be too surprised. Academics are quiet, bookish types, mostly middle-aged or older, while a lot of their students are aggressive young thugs recruited for some athletic skill.

Prof. Gregory — although, again, I quite liked his course — is a typically timid academic. You get an illustration of this in Lecture Six.

The prof. is talking about arguments over evolution in the early 19th century, long before Darwin’s On the Origin of Species came out in 1859. (If you thought that it was Darwin who first came up with the idea of evolution, go to the back of the class. Evolution was being hotly debated before Darwin was born.)

He discusses the conflicts in France between anti-evolutionist Georges Cuvier and various French proponents of the theory. Then:

The British scene reveals another reason why evolution could not gain wide support in pre-Origin years. Its supporters were often seen as radicals: not just because they embraced evolution, they frequently supported other radical causes, too — radical social causes, radical political causes, radical religious positions. Most people in polite society didn’t want to be associated with such individuals.

That went for Charles Darwin himself, as we'll see. If you were young, it could harm your career prospects to be known as one of those "transmutationists," as the English called evolutionists.

Science is more professionalized now than it was in the 1830s and 1840s, when the process was really just beginning; but still today, a budding young scientist would be prudent not to publicly endorse, say …

Yes? Prof., yes? — to publicly endorse … what?

… communism …

Huh?

… or atheism …

Seriously?

… or belief in alien abduction.

For Heaven’s sake!

If they [sic] became convinced of something like this, best keep it to yourself. Yes, I know, these things aren’t supposed to matter, just an individual’s scientific abilities and productivity as measured by commonly-accepted standards; but unfortunately these other things too often do matter. [Darwinian Revolution, Lecture Six: "Why Evolution Was Rejected Before Darwin," 23m42s et seq.]

An endorsement of communism will get you shut out of a position in scientific academia? From what I read about the Academy, it would be a positive advantage. Stephen Jay Gould’s book The Mismeasure of Man is required reading for many college courses, including some science courses; yet Gould was as near to being a communist as makes no difference.

Does Prof. Gregory not know the kind of endorsements that would get a young researcher (or even a very old one) shut out of the Academy nowadays? Or does he know, but is too timid to mention such things out loud? Or does he know, and is willing to mention, but was warned off doing so by the managers at the Great Courses company, which is after all a commercial venture operating in the sphere of what is socially acceptable?

Your guess is as good as mine.

Gemütlichkeit in Hong Kong. August started in Hong Kong, at the tail end of the Derbs' Far East vacation.

I expressed some personal feelings about Hong Kong in the very first of these diaries. Now, fifteen years later, that sentimental nostalgia has been much diluted by time and circumstance. I wouldn’t go so far as to say that Hong Kong is now, in my mental atlas, just a place; but the electric shimmer of fond remembrance and bitter regret has faded to a mere background tint. A Hong Kong friend we were visiting with told me that Chungking Mansions is still in business. Did I want to take a look? No, I didn’t.

Visiting with friends was in fact most of what we did in Hong Kong. I have acquaintances there going back to the early 1970s, and a surprising number of Mrs Derbyshire’s college classmates from northeast China now live in nearby mainland cities: Shenzhen, Zhuhai, Guangzhou.

These bonds among Chinese college classmates who all graduated thirty-odd years ago are very strong. I don’t know whether this is a generally Chinese thing, or a thing just of their time. When they started college in the late 1970s, higher education was just getting re-started after the Cultural Revolution (1966-76). Perhaps that made for an exceptionally strong sense of camaraderie.

Whether it did or not, there was a major upside to being among those first post-Cultural-Revolution graduating classes. China in 1983 had a dire shortage of college-educated young people. Businesses, universities, state bureaucracies, the professions, all sucked them in gratefully. Now, thirty years on, a high proportion of these classmates from a small provincial college are seriously wealthy.

They are all in touch through WeChat, China’s main social-messaging app. Hearing that we'd be in Hong Kong, several came over to meet us at, of course, a restaurant banquet. It was all very gemütlich.

The localist phenomenon. Grumbling about mainland Chinese incomers has been a popular Hong Kong pastime for decades.

In the early 1960s, refugees from the Mao famine came flooding over the border into what was then the British colony, depressing wages and stressing the very rudimentary social services of the place.

The border was more strictly controlled during the Cultural Revolution, but mainlanders got in anyway. Thousands of young mainlanders, disillusioned with all the chaos, or banished to poverty-stricken country areas in "rectification" campaigns against the Red Guards, came in by swimming the few miles of water between the two jurisdictions. In my sojourn there, 1971-73, Hong Kongers complained endlessly about how these daai-luk-jai (mainland kids) were useless for any kind of work. "All they know to do is just sit around arguing politics …"

I'd supposed that the grumbling might have faded with the rise of the New China. Not at all: if anything, it’s worse than ever. Mainlanders, people tell you, are arrogant and uncouth. The ones with money throw it around tastelessly, for show; the ones without bicker over the price of everything and leave (the taxi, the restaurant, the bar) without paying. They smoke too much; they spit; they let their toddlers crap on the sidewalk; etc., etc.

(In regard to spitting, Hong Kongers seem to have been totally cured of the habit. Forty-five years ago, when I was busily memorizing all the Chinese characters my eye fell upon, the signs on the Star Ferry from Kowloon to Hong Kong island begged 請勿吐痰 — "Please don’t spit" — to not much effect that I could see. The Star Ferry is still sailing — with some of the same boats, to judge by their physical condition — but the signs are long gone.)

The current political expression of this attitude is localism, a desire among many young Hong Kongers for Singapore-style independence. One Hong Kong friend, who lives in the precincts of the Chinese University, gave me the following striking illustration of localist sentiment.

Remember how there used to be candlelight vigils and so on every year in commemoration of Six-Four [i.e. the massacre of protestors in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square on June 4th, 1989]? Students now have stopped participating in that. "Nothing to do with us," they say. "That was a mainland affair. We're Hong Kongers."

The localist phenomenon is now prominent enough that The Economist ran a full-page article about it in the August 27th issue.

Localism is a no-hoper, of course. The control freaks in Beijing — especially the current Control Freak-in-Chief — will no way allow Hong Kong any more autonomy than the place currently has. The ChiComs in fact think it has too much and needs to be brought to heel, as you can see from the snarling of their paid trolls in the comment thread to that Economist article online.

The malling of Hong Kong. The main thing I noticed about Hong Kong this visit is how over-malled it is.

Elizabeth the First’s England was so well-forested, it was said that a squirrel could go from coast to coast without ever touching the ground. I swear you could go from one side of Hong Kong to the other — well, of the built-up area — without ever leaving a mall.

Every subway station, for example, comes with a mall attached. You get off your train, come out through the turnstile, and find yourself in a mall crammed with designer outlets.

Where do they get all their business? Who buys all that designer junk? I asked a couple of Hong Kong friends, and got the same response from both: a snort, a roll of the eyes, and then: "Mainlanders, of course!"

The art of the sub. Sub-editors, known around the office as "subs," are the folk who write headlines and picture captions for newspapers and magazines. It’s work that offers much scope for creativity and wit. (Including wit of the lower sort, as witness the New York Post’s headlines on ex-Congressman Anthony Weiner and his sexting adventures: "Weiner’s Rise and Fall," "Obama Beats Weiner," "Weiner: I'll Stick It Out," "Huma Cuts Off Weiner," etc., etc.)

So I wrote up my review of The Transylvanian Trilogy, as advertised in my May Diary, and shipped it off to The New Criterion for their September issue. Recall that this is a big social-historical-political novel in the nineteenth-century style, about the pre-WW1 Hungarian aristocracy of Transylvania.

Concerning whom, I say in my review that:

Like the Anglo-Irish Ascendancy, Hungarian aristocrats in Transylvania held their estates in a backward, agricultural land whose people were mostly of different religion and ethnicity.

Sending in the review, I didn’t put a title on it. For one thing, I’m not much good at titles. For another, editors generally prefer to make up their own anyway.

Okay, now see if you can guess the title some ingenious sub put on my review.

Give up? Here it is. I’m still chuckling.

The New Criterion — a tribute. And by the way, Congratulations! to The New Criterion as they embark on their thirty-fifth year of continuous publication. As the editors note in the preface to this September issue:

Serious cultural periodicals tend not to be long-lived … T.S. Eliot’s Criterion, from which we take our name and whose critical ambitions we seek to emulate, had a run of seventeen years, from 1922 to 1939.

I've been contributing to TNC for exactly half of its thirty-four years. A couple of years into that acquaintance I wrote an appreciation of the magazine. That was in the somewhat fevered days soon after 9/11; but reading it now, fifteen years later, I must say, if I were commissioned to write it today, it would come out much the same.

Congratulations! again, TNC, and here’s to the thirty-fifth year, and the next thirty-five to follow.

And whichever sub thought up that title for my Transylvania piece, give him/her/xe a raise!

Comrade Baron. In the annoying way these things happen, I did not know about Jaap Scholten’s recent book Comrade Baron until I read a review of it in the August issue of Literary Review.

Subtitled "A Journey through the Vanishing World of the Transylvanian Aristocracy," Comrade Baron is directly relevant to The Transylvanian Trilogy. From the blurb at Amazon.com:

In the darkness of the early morning of 3 March 1949, practically all of the Transylvanian aristocracy were arrested in their beds and loaded into lorries. Under the terror of Gheorghiu-Dej and later Ceausescu the aristocracy led a double life: during the day they worked in quarries, steelworks and carpenters yards; in the evening they secretly gathered and maintained the rituals of an older world. To record this episode of recent history, Jaap Scholten travelled extensively in Romania and Hungary and sought out the few remaining aristocrats who survived communism and met the youngest generation of the once distinguished aristocracy to talk about the restitution of assets and about the future.

However, by the time I spotted Scholten’s book in Literary Review, the September issue of The New Criterion was already in the hands of the printers, being pressed into cuneiform blocks and sent to the ovens for baking — too late for me even to add a footnote. Grrr.

Of course, if some kind editor would like to have a copy of Comrade Baron shipped to me in care of VDARE.com. I'll be glad to do a review to any required length at the usual word rates …

Math Corner. The summer Olympics came and went. I can’t claim any enthusiasm for the games as such, but I do smile quietly to myself thinking of all the Human Bio-Diversity (HBD) on flagrant display there. I also wonder, also quietly, what HBD-denialists — dogmatic nurturists — are thinking when they see, for example, an all-black set of finalists in the 100m sprint for the umpety-umpth Olympics in a row.

For an almost equally flagrant display of HBD, here are a couple of different olympiads from recent months.

First, the U.S.A. Math Olympiad for high-schoolers, this year held April 19th and 20th nationwide. Here’s a picture of the 12 top scorers. Here are their names (not necessarily in the order pictured): Ankan Bhattacharya, Ruidi Cao, Hongyi Chen, Jacob Klegar, James Lin, Allen Liu, Junyao Peng, Kevin Ren, Mihir Singhal, Alec Sun, Kevin Sun, Yuan Yao.

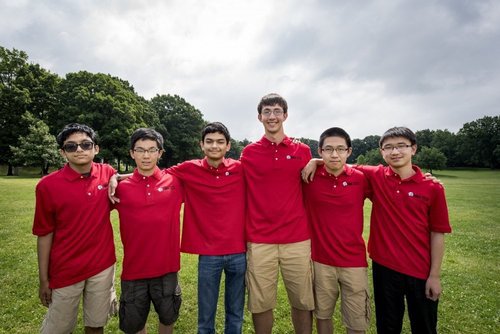

And then the international equivalent, which took place this year in Hong Kong, July 6th-16th. The six-member U.S. team took first place in the IMO for the second year running. Here they are: Ankan Bhattacharya, Michael Kural, Allen Liu, Junyao Peng, Ashwin Sah, and Yuan Yao.

*

Finally, a brainteaser.

Roll three normal dice. What is the probability of "getting a three"? That is, what’s the chance that the numbers that came up made a three in some combination: (1, 1, 1), say, or (1, 2, 4), or (1, 3, 2), or (5, 3, 1)? As opposed to numbers that don’t, like (1, 4, 1), (2, 2, 2), or (6, 5, 2)?

This should be straightforward. There are 216 equal-probability results of the throw. So you just have to count how many of those possibilities will "get" you a three, then divide that number by 216.

Yet for some reason it’s hard to get the answer right. The 16th-century genius and gambler Girolamo Cardano, who wrote the first book-length study of probability theory (and who I covered in Chapter 4 of Unknown Quantity), got it wrong. He also got the wrong answers for getting a four, a five, and a six on a roll of three dice.

Stephen Stigler, Professor of Statistics at the University of Chicago, gave this problem to his students two years running. He reports that only a third of them found the correct answer for "getting a three"; for "getting a four," less than a quarter of students got the right answer.

I myself had a go at the probabilities for getting a one, a two, a three, a four, a five, or a six. I set up a spreadsheet with 216 lines, one for each equal-probability outcome of the throw. Then I eyeballed through, marking up each outcome that made the number I sought.

I got the right answers for ones, threes, and fours, but not for twos, fives, or sixes (though I did better than Cardano).

What’s up with this?

John Derbyshire writes an incredible amount on all sorts of subjects for all kinds of outlets. (This no longer includes National Review, whose editors had some kind of tantrum and fired him. ) He is the author of We Are Doomed: Reclaiming Conservative Pessimism and several other books. He’s had two books published by VDARE.com: FROM THE DISSIDENT RIGHT (also available in Kindle) and From the Dissident Right II: Essays 2013. His writings are archived at JohnDerbyshire.com.

Readers who wish to donate (tax deductible) funds specifically earmarked for John Derbyshire’s writings at VDARE.com can do so here.