01/02/2018

New Year blues. I've reached the point in life when lamenting the end of another year comes more naturally than celebrating the beginning of a new one.How time flies! Another year gone already? After age seventy the passing scene more and more resembles the image one of Noël Coward’s characters supplied: it’s

like one of those montages you see in films where people jump from place to place very quickly and there are shots of pages flying off a calendar.

For example: The last time movie actress Diana Rigg impinged on my consciousness, she was young and beautiful. Heck, I can recall having erotic fantasies about her.

Now, it’s true that I pay very little attention to show business. It was mildly shocking none the less to see Ms Rigg’s picture at MailOnline Christmas Day, a wrinkled old lady. Damn this demon Time!

Reflections of this kind are so commonplace, it’s impossible to say anything original about them. Poets have been lamenting the aerodynamics of time for two thousand years at least.

I can’t compete with all that talent, so I'll leave this here as merely the registration of a New Year’s mood.

Lightless in the quarry. Continuing in the same gloomy key: For an overview of the whole show I have always thought King Vlad, in Speak, Memory, summed it up as well as it can be summed up:

The cradle rocks above an abyss, and common sense tells us that our existence is but a brief crack of light between two eternities of darkness. Although the two are identical twins, man, as a rule, views the prenatal abyss with more calm than the one he is heading for (at some forty-five hundred heartbeats an hour).In Eastern traditions, where reincarnation is taken for granted, that "prenatal abyss" is populated with earlier lives, human or otherwise according to regional taste. Which I guess means it’s not an abyss at all in those traditions.

We in the West have mostly let our imaginations loose on that second eternity, ignoring the first. The only reference to "the prenatal abyss" that I know of in English poetry is this one by A.E. Housman.

Be still, my soul, be still; the arms you bear are brittle,Earth and high heaven are fixt of old and founded strong.

Think rather, — call to thought, if now you grieve a little,

The days when we had rest, O soul, for they were long.

Men loved unkindness then, but lightless in the quarryI slept and saw not; tears fell down, I did not mourn;

Sweat ran and blood sprang out and I was never sorry:

Then it was well with me, in days ere I was born.

Now, and I muse for why and never find the reason,I pace the earth, and drink the air, and feel the sun.

Be still, be still, my soul; it is but for a season:

Let us endure an hour and see injustice done.

Ay, look: high heaven and earth ail from the prime foundation;For my favorite Housman story, see an earlier diary.All thoughts to rive the heart are here, and all are vain:

Horror and scorn and hate and fear and indignation —

Oh why did I awake? when shall I sleep again?

Gentlemen, the Queen! Some of this regrettable mood is a secondary consequence — induced nostalgia — of having watched the first few episodes of The Crown, Netflix’s biopic of England’s current Queen.

The show is very fascinating to me because the years covered so far, 1947-55, were those of my own childhood (ages 2-10). For a child, public events are distant and disconnected, the more so back in those days because we had no TV or internet, only newspapers and radio. Seeing those events played out as a connected narrative by professional actors adds a whole new dimension to those faint, random childhood memories.

I have fragmentary recollections of, for example, the matter of Princess Margaret’s affair with Peter Townsend. [GREAT BRITAIN: The Princess & the Hero, Time,July 20, 1953 ]I remember seeing pictures of the couple (right) in my father’s Daily Mirror, and hearing my mother in conversation about it with neighbor wives (they were all fiercely pro-Margaret). The Crown makes a real human-interest story of it.

The producers have striven for a high level of authenticity in their sets, too. The clothes, the cars, the planes!, the haze of cigarette smoke in every room … it’s very well done.

I've spotted a few anomalies. The Queen would not, in 1953, have referred to "… my age and gender." She would have said "sex," unselfconsciously.

The dentition, too, is very 21st century. Most English people in the 1950s had terrible teeth. The Queen Mother, for example: I came within a few feet of her when she opened a new building at my school in 1956, and I remember thinking at the time that her teeth were not very good.

They must have been bad indeed for me to have noticed. I was a working-class kid growing up among adults who smoked two packs of cigarettes a day, drank their tea with four spoonfuls of sugar in it, and went to the dentist only for extractions. (The Queen Mother’s teeth didn’t improve with age.)

Aside from a few quibbles like that, the sets, costumes, and speech of The Crown are wonderfully well done. I can well believe that, as the BBC says, The Crown may have cost more than the actual monarchy.

Reports have claimed the show’s first series cost a record $130m (£97.4m) — though its creator Peter Morgan thinks that’s nearer the total for both …Whether the storylines of The Crown are as true to life as the sets is open to doubt. Peggy Noonan wrote a withering piece about historical inaccuracies in Season 2 (which I haven’t got to yet). [The lies of The Crown will do harm, by Peggy Noonan, The Australian, December 30, 2017]The Crown is expected to run for six series. If their cost remains stable, that’s either $780m (£584m) if you believe the rumours, or (on Morgan’s figures), $390m (£292m). So if the monarchy does indeed cost £300m a year, that would fund three series of the Crown at worst. And, at best, all six.

I wouldn’t be surprised if she’s right. The First Commandment for mid-20th-century English people — for the upper classes even more, I think, than for us proles — was: Don’t make a fuss.

For living one’s life, that’s not a bad rule. For making TV drama, though, it won’t do at all. If people won’t make a fuss, where’s the drama? So I suspect the scriptwriters were encouraged to fill the fuss-less void with products of their own imaginations.

If so, it worked. Mrs Derbyshire, who grew up in a very different country and so has none of my nostalgia to draw her in (and who refers to the Queen’s consort as "the hamburger"), finds the show very gripping. I've enjoyed teasing her that the Chinese should have kept their Emperor: monarchy’s way more fun than a bunch of stone-faced commissars.

Teeming with kids. If I could get a time machine and go back to that England of the early 1950s, what would I find most striking about it?

One thing would likely be the sheer quantity of children around. There’s a reason why "Baby Boom" is an expression.

The place was teeming with kids. Every school had an annex to house the overflow; either prefabricated sheds or rented rooms in sufficiently spacious buildings. My elementary-school classroom in 1953-54 was the meeting hall of a nearby church. Class sizes averaged around forty.

John Derbyshire’s 1956 primary school class (he’s the white British child, fourth from the left at the back)

When I look up the actual statistics, I see that some of those impressions are probably magnified by particular circumstances. England’s post-WW2 baby boom peaked in 1947 at a Total Fertility Rate (TFR) of around 2.7 children per woman. That’s not actually stupendous: in today’s rankings it would put us between Swaziland and Haiti, far below champions like Afghanistan (5.12) and Niger (6.49). It came after a long trough in the 1920s and 1930s, though, so I guess that accounts for the shortage of classrooms.

And kids were around kids more. With no TV, and helicopter parenting far in the future, the words we most commonly heard from parents were: "Go out and play. Make sure you're home in time for supper."

Out we went into the street. Nobody owned a car, and there was essentially no traffic. You could easily get twenty or thirty kids together for a game of kingy or British bulldog.

The real baby boom, in both England and the U.S.A., was in the 1950s and early 1960s. The U.S. TFR figure for 1957 was 3.7, between today’s Yemen and Rwanda.

Still, today’s childhood is a solitary affair by comparison; and with plummeting fertility rates all over the civilized world, it won’t get any less solitary.

The Puritan comeback. December means Christmas, and that means the War on Christmas, which VDARE.com has been documenting for years now.

This year the Southern Poverty Law Center piled on. Why on earth does anyone still take those people seriously? Morris Dees, begetter and supremo of the $PLC, is the P.T. Barnum of our age.

P.T. Barnum: There’s a sucker born every minute.For those of us who think that Cultural Marxism has just co-opted the religious modules in the human brain, the War on Christmas offers neat confirmation. After all, the first War on Christmas was conducted by the Puritans.P.T. Barnum’s assistant: OK, but where do all the rest of them come from?

Christmas in 17th century England actually wasn’t so different from the holiday we celebrate today. It was one of the largest religious observances, full of traditions, feast days, revelry and cultural significance. But the Puritans, a pious religious minority (who, after all, fled the persecution of the Anglican majority), felt that such celebrations were unnecessary and, more importantly, distracted from religious discipline. They also felt that due to the holiday’s loose pagan origins, celebrating it would constitute idolatry. A common sentiment among the leaders of the time was that such feast days detracted from their core beliefs: "They for whom all days are holy can have no holiday."You can’t help thinking there’s something to be said for the notion that history just goes round in circles.

Nonfiction books of the month. This month I read one and a half books about reason.

The one I read all through was The Enigma of Reason by two cognitive-science researchers, Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber.

What’s up with reason? What’s it for? How did it emerge from the slow churnings of evolution?

If you ask people, most would say that reason advances our survival prospects by helping us, each one of us individually, to make sense of our perceptions, to extract useful information from the flood of incoming data. The authors call this the "intellectualist" approach.

They say it’s wrong, and oppose it with an "interactionist" approach. We have reason because we are social critters, they say.

The ability to produce and evaluate reasons has not evolved in order to improve psychological insight but as a tool for defending or criticizing thoughts and actions, for expressing commitments, and for creating mutual expectations. The main function of attributing reasons is to justify oneself and to evaluate the justifications of others.In that case, you may ask, what about the solitary genius — Isaac Newton, for example, deducing deep truths about the nature of the world while sitting alone under the proverbial apple tree at Woolsthorpe during the Plague Year?

The authors have answers for that, and for any other objections you might come up with. It’s a good argumentative book — as, considering its thesis, it should be …

Thus fired up, I thought I'd tackle The Rationality Quotient: Toward a Test of Rational Thinking by three academic psychologists, Keith Stanovich, Richard West, and Maggie Toplak. I'd read Keith Stanovich’s article "Were Trump Voters Irrational?" at the Quillette website back in September, and had the book in mind as a possible read.

This is the one I didn’t finish. I flatter myself I got the authors' main point; but this is heavy-duty cog-sci, and my brain’s not up to the required level of prolonged concentration.

The main point: rational thinking involves something not captured by traditional IQ-based psychometry. The authors aren’t anti-IQ; they're actually respectful towards traditional psychometry. They just think there’s more to rationality than merely "algorithmic" processing.

We've all gotten used to the dual-process model of thinking from reading Kahneman’s Thinking, Fast and Slow. Fast thinking is intuitive, approximate, and not very demanding of resources. Slow thinking is painstaking, more accurate, and cognitively demanding. Slow thinking is the domain of reason.

Yes, say the authors, but there are two different kinds of rational processing going on in slow thinking. One is the "algorithmic" thinking that IQ tests capture — "individual differences in fluid intelligence." The other is reflective — "individual differences in thinking disposition."

To be rational, a person must have well-calibrated beliefs and must act appropriately on those beliefs to achieve goals — both properties of the reflective mind.The two kinds of rationality aren’t well correlated; so we need something else beyond IQ tests to assess a person’s rationality. That’s what these authors are aiming for: a Comprehensive Assessment of Rational Thinking (CART). There are sample tests at the back of the book.

The Rationality Quotient is, as I said, dense and academic. There are some nifty turns of phrase, though. I liked the Virgilian-sounding "islands of false beliefs" that people get stuck on when gripped by pseudoscience or conspiracy theories. The whole discussion of why smart people often believe crazy things is worth the book’s price. (The chapter title is "Contaminated Mindware.")

Why did I buy these two books? I don’t precisely remember, but I’m sure there was a good reason.

Fiction book of the month. Harry Turtledove’s How Few Remain, gifted to me by a pal at the Mencken Club conference in November, was a good read.

The novel is Alternate History: How would events have diverged if one small thing had happened differently?

The one small thing here is a famous incident during Robert E. Lee’s Maryland campaign in September 1862. Lee had marched west out of Frederick, Maryland. A Union regiment, paused for rest at what had recently been a Confederate camp site, found three cigars "wrapped in a sheet of official-looking paper" (Shelby Foote).

The paper turned out to be Lee’s Special Orders 191, describing his plan for the campaign. It was soon in the hands of George McClellan, the Union commander, who exulted that: "Here is a paper with which if I cannot whip Bobby Lee I will be willing to go home."

Fortunately, Lee found out almost immediately what had happened; so McClellan knew Lee’s planned dispositions, but Lee knew that he knew. There followed some frantic military-strategic chess moves that culminated in the tremendous Battle of Antietam, enough of a win for the Union to send Lee back to Virginia.

In the novel this didn’t happen. Confederate soldiers breaking camp see the courier drop that package. They hand it back to him. Lee’s plan goes ahead undisturbed, and the South wins the Civil War.

The book’s main action takes place twenty years later. The Confederate States have acquired Northern Mexico, prompting the U.S.A. to declare war again. We follow the progress of this second war between the states to its conclusion.

Everybody who’s anybody in 1880s North America is in the book: Theodore Roosevelt, Geronimo, Mark Twain, Frederick Douglass, James G. Blaine ("continental liar from the state of Maine"). Some actual Civil War fatalities have survived in this alternate world: Abraham Lincoln is a down-at-heel lecturer for socialism; Stonewall Jackson commands the Southern armies; Jeb Stuart’s fighting Indians in the Southwest. George Armstrong Custer’s a Union colonel, having somehow avoided his fate at Little Bighorn.

Our author seems to have read all the biographies. At any rate, my own scant knowledge of these characters is not contradicted by anything he writes.

I especially liked the absence of moralizing and "diversity" promotion — the imposing of early 21st-century social fads on 19th-century events. I kept finding myself thinking: "Yes, that’s what he would have said (or done)."

That applies to Frederick Douglass. He talks the way one imagines Douglass did talk. We're not being preached at here. Slavery is an issue in the war, but only because of an understanding that Britain and France will support the South on condition that the South, if victorious, will free the slaves.

How Few Remain was published in 1997. Harry Turtledove — that’s his real name — was born in 1949, so he reached maturity pre-PC. Can novels like this — calmly accepting of past attitudes and manners, with no Progressive moralizing gloss — still be published?

Steve Sailer tells us that publishers are now using "sensitivity readers" to make sure the fiction they publish contains nothing that might offend the infinitely tender sensibilities of Millennials. The movie Gone with the Wind "is now rarely screened, even in museums," and I feel sure there are citizens' groups trying to get the book withdrawn from libraries and bookstores.

Now I am thinking of the late George MacDonald Fraser, who wrote the Flashman novels. Those books are more fun, more improbable, and wittier than How Few Remain, but they have the same easy-going understanding that the past was a very different place, and that it is not the business of middlebrow novelists to pass judgment on it.

Is that understanding still with us?

Totalitarian capitalism (cont.) At Radio Derb a couple of weeks ago I had a segment titled "Totalitarian capitalism," deploring the capture of major corporations by Social Justice Warriors, as illustrated by Twitter’s December 18th purge of Dissident Right accounts.

I intended, but forgot, to add a link in the transcript to Carl Horowitz’s talk at the Mencken Club on this very topic. It’s titled "The Corporation and Political Radicalism: a Bad Business Partnership."

Sample:

What I’m referring to is the arms-length agreement between corporations and far-Left activists to subvert deeply ingrained human loyalties, especially those related to national identity. Most corporate executives today see America’s future as post-national, not national. The two factions differ by motive. Businessmen act out of material self-interest. They want to hire people from abroad at much lower wages and benefits than the native-born would accept. And they want to sell in untapped markets. Radicals, by contrast, act out of emotional self-interest. They crave total multiculturalism in one nation, that feeling of singing in unison, "We Are the World."That’s what I was getting at: the rapport, the unity of interest between the moral vanity of Progressives — the emotional rewards they get from advertising their love-the-world goodness — and the avarice of capitalists.Where these camps converge is the belief that national identity is outdated and must be replaced by an elaborate system of global coordination. A nation ought to have no right to define itself in terms of race, language or collective memory. In the world of information technology, in fact, business and radicalism now mean almost the same thing.

This is what’s shaping our age, not Marx’s struggle between proletariat and bourgeoisie. Will it end, as Marx’s program ended, in chaos and mayhem? Or are we too soft, plump, and infantilized to fight for our liberties?

I guess the latter. Here’s my phrase of the month, courtesy one of Steve’s commenters: "the nerf-gun Cultural Revolution."

In the realm of buncombe. Browsing the Daily Mail website at Christmas, my attention was caught by this headline: The conspiracy theorists who think the Earth is HOLLOW: Growing community believe superior "alien" humans, Vikings and Nazis live in paradise in the centre.

The lead conspiracist here is "author Rodney Cluff." What’s he author of? Oh right: World Top Secret: Our Earth IS Hollow!: The Scientific, Scriptural and Historical Evidence that Our Earth Is Hollow!

Says the Daily Mail:

Instead of thinking that the world is flat, they are convinced that it actually contains a paradise at its core that resembles the Garden of Eden.It’s nuts, of course, but I don’t think it’s any more nuts than the no-such-thing-as-sex, no-such-thing-as-race buncombe currently being taught in the Humanities departments of our univerities.The "hollow-Earthers" even believe UFOs are sent from the globe’s interior by "guardians of the planet" to spy on the human race and avert a potential nuclear war …

[Cluff] is so confident in his theory that he organised a voyage to the hollow Earth in 2007 via an "opening" in the North Pole.

Although the £15,000-per-head expedition was cancelled, Cluff is convinced that an inner paradise with its own solar system exists.

As well as being nuts, it’s also deeply unoriginal. I remember reading about Hollow Earth Theory in Martin Gardner’s Fads and Fallacies in the Name of Science not long after 1957, when Gardner’s book was published. Patrick Moore’s 1972 book Can you Speak Venusian? covered the theory, too.

Wikipedia has references from the 17th century; and ideas about the Underworld, which probably go back to prehistoric times, are obviously related.

It’s not true that there is nothing new under the sun. Darwin’s (and Wallace’s, if you want to be punctilious about it) idea of evolution by natural selection was new; the curved spacetime of General Relativity was new; quantum superposition was new.

In the realm of buncombe, though, nothing is new.

Resolutions. New Year Resolutions? The usual stuff: Drink less, work less, read more, exercise more.

There is one thing I really need to do this year, though: Update my personal website.

I built the thing ten years ago and it’s showing its age. Flash is on its last legs, and Adobe will stop supporting it in 2020, so I need to move to HTML5.

To do the mass changes I need to do (once I've figured out what they are) I need to do some coding, and my coding skills have become badly decayed across the decade. On the advice of several friends still in the trade, I’m going to learn C#.

I should transcribe the earliest Radio Derbs, too; and make an audio version of Fire from the Sun, …

And a few lesser updates and adjustments. I'd like to think that if I fall off my perch, my website will survive for a few years.

There, you see? I've returned to the somber key I started in.

Math Corner. If you like counterintuitive results, there’s a neat one in the Winter 2017 issue of The Mathematical Intelligencer (Vol. 39, No. 4, pp. 41-45.)

The article works its way up to some fairly heavy-duty math, but it opens with a question anyone can understand. I'll break it down into steps.

On November 16, 2013 Molly Huddle ran 37:49 for 12 kilometers, a world record for that distance. [Technically a world best, as 12 km is a nonstandard distance.]Good for her. What then?

People applauded this fine performance, but some pointed out that Mary Keitany’s [then] world record of 65:50 for the half marathon, which is 21.1 kilometers, was actually faster than Huddle’s record.How so?

Keitany averaged 3:07 per kilometer whereas Huddle averaged 3:09 per kilometer.Uh-huh. So what’s the question?

Therefore, Keitany must have run some 12-km subset of the race faster than Huddle — right?The intuitive answer is "yes." The actual answer is "no, not necessarily"

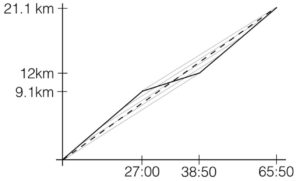

A graph explains. Suppose for example — and this explanation works for any number of similar examples — that Keitany ran 27:00 for the first and last 9.1 km, and 11:50 for the middle 2.9 km. Then her total time for the race would still be 27:00 + 11:50 + 27:00 = 65.50, but her time for each 12-km subinterval would have been 27:00 + 11:50 = 38:50, much slower than Huddle’s record.

The graph has time along the x-axis, distance along the y-axis, so the slope of a line is speed (distance ÷ time). The solid dark line shows Keitany’s run under the "suppose" I just supposed. The slope of the dashed line is her average speed. The fainter grey lines are 12-km subintervals. Every one has a slope (= speed, remember) less than Keitany’s overall average speed.

I won’t go much deeper into the math here. If you're interested, hike over to your nearest college library and look up the article in Intelligencer.

I can’t resist, though, one reference to a neat general theorem that is equivalent to the running problem. It was first proved in 1934 by Paul Lévy. The key concept here is that of a chord, which is just what you think it is: a straight line joining two points on a graph.

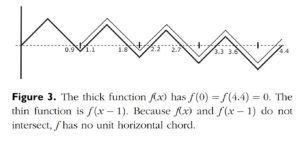

Theorem. For any positive noninteger L > 1, there is a continuous function f : [0, L] → R with f (0) = f (L) = 0 whose graph has no unit-length horizontal chord.Counterintuitive again; but again, a graph tells the story.

John Derbyshire writes an incredible amount on all sorts of subjects for all kinds of outlets. (This no longer includes National Review, whose editors had some kind of tantrum and fired him. ) He is the author of We Are Doomed: Reclaiming Conservative Pessimism and several other books. He has had two books published by VDARE.com com:FROM THE DISSIDENT RIGHT (also available in Kindle) and FROM THE DISSIDENT RIGHT II: ESSAYS 2013.

For years he’s been podcasting at Radio Derb, now available at VDARE.com for no charge.His writings are archived at JohnDerbyshire.com.

Readers who wish to donate (tax deductible) funds specifically earmarked for John Derbyshire’s writings at VDARE.com can do so here.