DERB’S JANUARY DIARY [9 ITEMS]: Paul Johnson RIP; CLAREMONT REVIEW; Kids Don’t Read: Medical Interlude With (Then Without) Gallbladder; ETC.!

02/06/2023

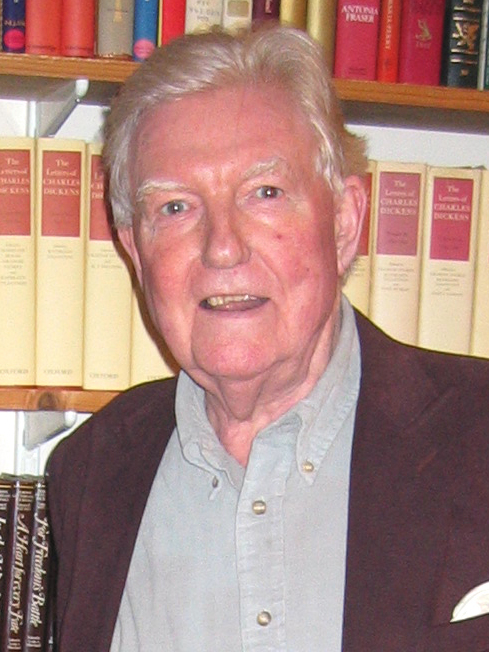

Paul Johnson RIP. British writer Paul Johnson died on January 12th at age 94.

Hearing the news I felt as though I’d lost the other party in a friendship going back decades, but which I’d been neglecting for the latter half of that span.

That’s “felt as though.” I wasn’t a personal friend of P.J.’s. I only met the man in person once, at a Library of Congress event in the late 1990s. I introduced myself, we exchanged some brief pleasantries about the event, whatever it was (I’ve forgotten), and he turned away to speak to others.

I had been reading him since my college days in the mid-1960s, though. At that time he was on the political left. In fact he was editor of New Statesman, Britain’s main leftist weekly magazine. I was a lefty myself so there was no contradiction there.

I took a liking to P.J.’s prose early on. When the week’s New Statesman came out I turned first to his editorial page, published under the heading “London Diary.” Some of his throwaway remarks stuck in my mind for decades afterwards.

Here is an example from July 2003, when I was writing for National Review. Peter Robinson had organized a Q&A with P.J., we National Review hacks supplying the Qs and P.J. the As. Here was my contribution.

(Note that by this point P.J. had been on the political right for over twenty years. In the late 1970s he had become an ardent admirer of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan and had switched his regular weekly commentary from New Statesman to The Spectator. We were in sync there: my own political orientation had taken the same turn at about the same time.)

Robinson: John Derbyshire asks — well, let me simply read his question: “Back in the 1960s when Paul Johnson was Editor of the London New Statesman, I was a devoted reader of that journal. I recall that in one of his weekly diaries he passed an observation to the effect that there were only two things he was sure of: One, that money is the root of all evil, and two, that the only cure for unhappiness is hard work. I should like to ask Mr Johnson whether in the subsequent years he has revised his opinion on either of these points.”P.J.: Ah, that’s the kind of question one loves to hear. Something from a reader who still remembers what one wrote 40 years ago. It can certainly lead to evil, but, no, I no longer believe money is the root of all evil. And on hard work, I haven’t really changed my mind. It is a cure. And it’s a part of every cure.

That later position of P.J.’s is of course correct. Money can certainly help to advance evil, as with the vast sums George Soros is spending to undermine Western Civilization. The greatest evil-workers of recent times, however — Lenin, Hitler, Mao, Pol Pot — were not driven by love of money but by love of power.

The other part — that the only cure for unhappiness is hard work — needs slight qualification. I wouldn’t rule out the possibility that heedless hedonism, perhaps even addiction to alcohol or narcotics, might cure unhappiness at least for a while. So: The only personally and socially healthy cure for unhappiness is hard work. That’s better.

The man and the work. P.J. was an opinion journalist in his heart and soul. He didn’t just want to record things, he wanted us to know what he thought about them.

However, his prodigious intellect and tireless appetite for reading made him a very superior kind of opinion journalist, perhaps lifting him above that classification altogether into the ranks of scholarship. P.J. didn’t pull his opinions out of thin air; he grounded them in long hours of reading and reflection.

It shows in the bibliographies (usually “Source Notes”) at the ends of his books. I tallied the following number of pages of bibliography to some of his popular histories.

- A History of Christianity (1977): 15 pages.

- Modern Times: A History of the World from the 1920s to the 1980s (1983): 54 pages.

- A History of the Jews (1987): 37 pages.

- The Birth of the Modern: World Society 1815-1830 (1991): 71 pages.

- A History of the American People (1997): 84 pages.

There is a definite upwards trend there. I think it got to be too much for his publishers. Around the year 2000 P.J. decided to write a history of art, a subject of deep interest to him. (His father was, like Kipling’s, an art instructor.) When the book came out in 2003 it included this in its preface:

I have put everything I know and feel deeply into this book. It tries to cover all time and the world and, in the process, threatened to become prohibitively expensive and bulky. So I was obliged to cut it, for the first time in my life as a book writer, and the pain has been acute. I have left out source notes and bibliography for the same reason. I beg readers to forgive the omissions.

I have a mental image of P.J.’s publisher, 800-odd pages of manuscript already piled up on his desk, receiving the author’s 100-odd additional pages of bibliography and shrieking “NOO-OO-OOO!…”

P.J. wasn’t infallible in his opinions, but even when I disagreed with what he was saying — with his Catholicism in The Quest for God (1996), for example — I always felt I was dealing with a highly civilized person with whom, if we could discuss things in person, I’d find common ground and likely come away knowing something I didn’t know before.

On points of fact he, like Homer, occasionally nodded. The most famous such incident was when, in the first edition of A History of the American People, he translated John F. Kennedy’s declaration Ich bin ein Berliner to mean “I am a hamburger.” A berliner is not a kind of hamburger; it’s a kind of jelly donut. (The error was corrected in later editions of the book. And no, JFK’s German listeners did not suppose he was describing himself as a jelly donut. They took his declaration in the spirit intended.)

If I were asked to name my favorite among P.J.’s books… I couldn’t. I mean, I’d give a different answer if asked on different days. One of those answers would surely be Intellectuals (1988), though.

That’s the book where P.J. offers a parade of would-be world-improvers and saviors of humanity from the past three hundred years — Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Karl Marx, Tolstoy, Hemingway, Sartre, James Baldwin, and so on — and shows us what awful people they were. While professing love for humanity in the general, they had not much patience with human beings in the particular.

The chapter on Bertrand Russell, for example, burst a bubble I had been caressing since my student days: an admiration for Russell based on his writings about math and his History of Western Philosophy (which even P.J. allows is a “brilliant survey… the ablest thing of its kind ever written and… deservedly a best-seller all over the world”). The Cold War revealed Russell to be an impulsive and inconsistent thinker where public affairs were concerned, and none too honest. Nor does the philosopher’s sex life shine bright under P.J.’s close scrutiny: “a long tale of petty adulteries,” etc. So we lose our idols.

I had better stop or I shall fill this whole diary with commentary on Paul Johnson. As I started by saying, Derbyshire-Johnson has been like a dear old friendship too long neglected. Rest in peace, P.J.

Sharpe novels. So how am I getting on with Bernard Cornwell’s Sharpe novels?

Finished ’em, all 22. (We are promised a 23rd in November this year; and three short stories are sometimes included in the lists. I’m sticking with the 22 extant novels, though.)

An interesting feature of this series is that the order in which the 22 novels were published is different from the order of events in the narrative. Here’s the publication order:

Sharpe’s Eagle (1981)

Sharpe’s Gold (1981)

Sharpe’s Company (1982)

Sharpe’s Sword (1983)

Sharpe’s Enemy (1984)

Sharpe’s Honor (1985)

Sharpe’s Regiment (1986)

Sharpe’s Siege (1987)

Sharpe’s Rifles (1988)

Sharpe’s Revenge (1989)

Sharpe’s Waterloo (1990)

Sharpe’s Devil (1992)

Sharpe’s Battle (1995)

Sharpe’s Tiger (1997)

Sharpe’s Triumph (1998)

Sharpe’s Fortress (1999)

Sharpe’s Trafalgar (2000)

Sharpe’s Prey (2001)

Sharpe’s Havoc (2003)

Sharpe’s Escape (2004)

Sharpe’s Fury (2006)

Sharpe’s Assassin (2021)

Here, however, is the chronological order; that is, the 22 books in order by the years the narrative covers:

Sharpe’s Tiger — 1799

Sharpe’s Triumph — 1803

Sharpe’s Fortress — 1803

Sharpe’s Trafalgar — 1805

Sharpe’s Prey — 1807

Sharpe’s Rifles — 1809

Sharpe’s Havoc — 1809

Sharpe’s Eagle — 1809

Sharpe’s Gold — 1810

Sharpe’s Escape — 1810

Sharpe’s Fury — 1811

Sharpe’s Battle — 1811

Sharpe’s Company — 1812

Sharpe’s Sword — 1812

Sharpe’s Enemy — 1812

Sharpe’s Honor — 1813

Sharpe’s Regiment — 1813

Sharpe’s Siege — 1814

Sharpe’s Revenge — 1814

Sharpe’s Waterloo — 1815

Sharpe’s Assassin — 1815

Sharpe’s Devil — 1820-1821

Writing the books out of chronological sequence like that has involved the author in some slight adjustments from one edition of a book to the next, and in a few inconsistencies. If you’re interested in how he’s managed this, you should probably read them in publication order.

I’m not. For me, the narrative is the thing, not authorial mechanics. I’d love to have dinner with Bernard Cornwell; but as a recreational reader I’m more interested in Richard Sharpe.

Cornwell sure is a narrative genius, though. I read all 22 books in chronological order straight off, never ceasing to want to know What Happens Next. I shall read the new one when it comes out in November: Sharpe’s Command, covering yet more events in 1812 and so fitting in somewhere between Battle and Honor. Keep ’em coming, Bernie.

(For more on the two different sequences of the novels, see here. And a reader tells me I can watch the British TV adaptation of some of the narrative for free here if I sign up to a VPN. I probably should use a VPN — friends keep telling me I should — but I’ll pass on the TV adaptation. Just not a visual person; most movies send me to sleep.)

Claremont Review. In the matter of opinion journalism I can’t resist a brief shout-out to Claremont Review of Books, which has the highest concentration of good-quality opinionating — not all of it embodied in book reviews — of any periodical I know. The Fall 2022 issue is a real gem.

- Charles Murray on diversity.

- David Goldman on possible war with China.

- Myron Magnet and Bradley C.S. Watson (separately, a review and an essay) on Clarence Thomas.

- Theodore Dalrymple on Andrew Scull, madness, and the future of psychiatry.

- Michael Anton on nukes.

- Christopher Caldwell on Boomers and the relation between creative work and the businessfolk who promote it.

And much more strong, nourishing reading matter. I have no interest, financial or otherwise, in CRB; I’m just really glad it’s there.

Colette. Mid-month our Saturday night movie rental was Wash Westmoreland’s Colette (2018). Sure enough I fell asleep around the 45-minute mark, but not before the thing had piqued my curiosity.

Colette

Was her fiction any good? I thought I’d take a look. My local library had the Collected Stories (1983), so I checked it out.

My first impression was that this is the girliest writer I have ever encountered. Kingsley Amis’ Jake came irresistibly to mind.

Jake did a quick run-through of women in his mind, not of the ones he had known or dealt with in the past few months or years so much as all of them: their concern with the surface of things, with objects and appearances, with their surroundings and how they looked and sounded in them …

Reading more, though, I developed some respect. Colette’s territory is the feelings of women towards men and other women, and the hopelessness of finding lasting joy in male-female bonding. She was herself bisexual and wrote in a way very frank for her time about sexuality of all kinds and related issues like abortion. I’m guessing she is a major fixture in the syllabi of college Gender Studies courses.

It was probably that frankness that accounted for her fame. It sure wasn’t a narrative gift. Narratively, Colette is the anti–Bernard Cornwell. Instead of being pulled forward by the desire to know What Happens Next, I more often found myself stuck in a swamp of mushy prose wondering What Just Happened?

If you can get yourself into that hyperfeminine frame of mind, though, there’s some not-bad stuff here. The Kepi (1943), for example.

The Kepi: The first-person author is remembering herself as a 22-year-old struggling writer in late-1890s Paris. She befriends Marco, a woman twice her age, also a struggling writer. Marco is long separated from her husband and has never had a lover. Her husband, however, sends her money from time to time.The author does some missionary work on the older woman: improving her fashion sense, makeup skills, and so on. Now Marco acquires a lover, a young army officer.

In the happiness of the affair she becomes careless of her appearance, putting on weight. Larking around in bed one day she tries on her lover’s kepi. That gets a severely negative reaction from him, and he dumps her. Following Paul Johnson’s advice, she takes refuge in hard work.

Why that severely negative reaction? Was the lover reminded of some gay affair with another soldier? Did the kepi just emphasize Marco’s having lost her looks somehow? We are given no clue. What Just Happened?

(I got a nostalgia fizz from The Kepi. In my schooldays I was a keen reader of the British boy’s magazine Eagle. One of the comic strips therein was Luck of the Legion — the French Foreign Legion, that is.

The comic lead in that strip, Legionnaire Bimberg, was forever losing or abusing his kepi.)

Kids don’t read. Wow, this has been a bookish Diary, hasn’t it? I’m starting to feel like an anachronism in that regard.

I never see people reading books anymore. On commuter trains, the subway, waiting rooms,… everyone’s diddling with his gadget. You know: that gadget that enables the authorities to follow your every movement and transaction.

This isn’t going to get better. Kids are reading less and less. Pew Research quantified the decline a few months ago:

Among 13-year-olds surveyed in the 2019-20 school year, 17 percent said they read for fun almost every day, a smaller percentage than the 27 percent who said this in 2012 and roughly half the share (35 percent) who said this in 1984. About three-in-ten students in this age group (29 percent) said they never or hardly ever read for fun, up 21 percentage points from the 8 percent who said the same in 1984.

The Culture Wars aren’t helping. Came the Great Awokening, lefty schoolteachers started adding anti-white and gender-bender books to their classroom supplies to get the kiddies on board with the Cultural Revolution. The authorities should of course push back against this, but how?

I just read an opinion piece by a Florida 3rd-grade schoolteacher named Andrea Phillips. She’s obviously a lefty and the piece is written from that angle, but it makes a good point none the less.

The point is that careful vetting of books in the classrooms is (a) time-consuming and expensive (i.e., for the school district) and (b) perforce subjective. In states like Florida that have passed legislation about classroom book content, the subjective factor will encourage a better-safe-than-sorry minimalism. That, combined with the cost factor, may just end with no books in the classroom at all.

Andrea Phillips’ article is illustrated with a picture of empty classroom bookshelves. That’s a mighty sad picture.

“I’m done! I’m done! What do I do now?” Every teacher, in every classroom, hears this many (thousands) of times daily from their students. In my classroom, for more than a decade, the answer has always been “Get a book and read.” That is until last week… https://t.co/pp2VRX7kXf

— Florida Freedom to Read Project (@FLFreedomRead) February 2, 2023

I love Ron DeSantis and I don’t want my country’s 3rd-graders exposed to pornography and anti-white propaganda. How to manage this, though? Perhaps we should just ban from the classrooms all books published later than 1960.

Chinese (Lunar?) new year. Sunday, January 22nd was the first day of Chinese New Year. Or is it Lunar New Year? The Language Police are taking an interest.

It is important to recognize that Lunar New Year and Chinese New Year are not interchangeable terms, as using Chinese New Year to refer to the holiday celebrated by other cultures beyond China can be disrespectful and dismissive of their traditions.

”Lunar,” “Chinese”: Which is properly diverse and respectful, which is colored with Hate?

I’m afraid this kind of pettifogging infantilism turns my thoughts to homicide. Semantically of course “Chinese New Year” is better as a lunar New Year might occur anywhere on the calendar. Jewish New Year, Rosh Hashanah, is determined partly by phases of the Moon: it can fall on any date between September 5th and October 5th. An Islamic New Year can occur anywhere at all in the Gregorian calendar: this year, July 19th.

That’s just semantic nitpicking, though. Call it Lunar, call it Chinese; everyone knows in context what we are talking about.

The main thing we and our Chinese friends do at New Year is eat like hogs. Saturday, New Year’s Eve, we went to one of those friends for a banquet with around twenty other guests. There was food enough for fifty, but we did our best.

Sunday, New Year’s Day, it was our turn to host. We didn’t try to compete with the previous day’s gorge-a-thon, just family and two sets of husband-wife friends. Mrs. Derbyshire excelled herself, though, and I shall be dining on leftovers for the rest of the week.

What can I tell ya? It’s a food culture.

Medical interlude. January ended in the local hospital. I’m not a big fan of geezers talking about their ailments; but readers have expressed curiosity and there may be lessons of general utility in here somewhere, so I’ll give an account.

Wednesday afternoon, January 25th: Intense gripping pain right across my chest. OMG I’m having a heart attack! Conscripted Mrs. D to drive me to the local hospital ER. Checked in under “Chest Pain.”

The ER runs on scripts. Chest pain? They’ll administer every kind of test there is on your heart and lungs. I had at least two EKGs, a chest X-ray and a CT scan, blood tests,… the whole deal.

The ER was terrifically crowded this weekday afternoon, invalids on gurneys along both sides of the corridor, doctor visits infrequent and brief. There were long waits between tests — up to an hour. On the plus side, I got two shots of morphine for the pain. Ah, morphine!

Around 11 p.m., after I’d been seven hours in the place, the doctor showed up again. He’d scrutinized all my tests and… everything looked perfectly normal.

Say what? It had hurt like a bitch (although at this point it no longer did). How could everything be normal?

He shrugged. “May be a G-I matter.”

The dumb part of my brain actually wondered for a minute there what my condition had to do with infantrymen. Then the smarter part kicked in to translate from the Hospitalese: Gastro-Intestinal.

”Really? How can that be?”

He shrugged. “Esophageal spasm, perhaps. ’Scuse me, gotta go. See your family doctor in the morning.”

I discharged myself and went home.

Thursday, January 26th: See my family doctor — yeah, right. I don’t know how it is in your neck of the woods, reader, but if I want to see my family doctor at less than a week’s lead time, I have to zip-tie his receptionist and kick in his office door.

I did get to see his PA. I gave her the ER discharge papers. “Chest pain” they said all over. She did another EKG, drew some blood, and told me to make an appointment with a cardiologist.

Back home I asked Dr. Google about esophageal spasm. Sure enough:

Esophageal spasms can feel like sudden, severe chest pain that lasts from a few minutes to hours. Some people may mistake it for heart pain…

Had I overdone the Chinese New Year pig-out? Possibly; but the pain had gone, so maybe the thing had fixed itself. Didn’t bother making a cardiologist appointment. Hadn’t my tests all come through normal? Got a good night’s sleep.

Friday, January 27th: All clear until afternoon, then the pain came back. After midnight it started ratcheting up fast, through the 5 and 6 level into the 7 and 8. Mrs. D had gone to bed and I didn’t want to wake her; but…

Saturday, January 28th: …around 5:30 a.m. Saturday the pain level hit 10. I woke the Mrs. She drove me to the ER again.

The ER offered a striking contrast. Wednesday afternoon it had resembled the Atlanta scene in Gone With the Wind, groaning bodies everywhere. Now, at 6 a.m. on a Saturday morning, the lobby was empty. No gurneys in sight, check-in clerks dozing at their stations.

On an inspiration I registered myself in with “Abdominal Pain.” This got me a whole different battery of tests — including, I was surprised to see, a sonogram. The porter who wheeled me to the sonogram room was a middle-aged gruff Long Islander. To lighten things up a little I quipped: “Sonogram? Do they think I’m pregnant?” He: “Nowadays, who the f*** knows any more?”

After this round of tests — it’s now Saturday afternoon — I got some real doctor time, from a surgeon, no less. He had a tentative diagnosis: gall bladder enlarged and inflamed. “A couple more tests. If we’re right… surgery.”

Sunday, January 29th: This morning the surgeon sounded much more sure. Yep, gall bladder. Gotta come out. They don’t do surgery on Sunday unless they really have to; don’t want to pay overtime, perhaps… I don’t know. Anyway, I’m scheduled to go under the knife Monday.

Spent the day reading, dozing, watching daytime TV (which seems to be populated entirely by black people).

Monday, January 30th: Around 4:30 p.m. got wheeled off to the OR, which has a double set of double sliding doors. Above them is a big red-and-white sign saying NO EXIT. Hmm.

At last the magic moment. “Here we go,” says the anesthetist, and the universe — time and space both — ceases to exist for twelve hours. Why do I feel ashamed at liking that moment so much?

Tuesday, January 31st: Ended the month post-op, to be kept in hospital one more day for observation. The surgeon came, declared himself satisfied. He described my gall bladder, when he’d gotten to it, as “angry.”

I like that. Angry organs! I asked him if he’d saved it so that I might clean it up and get it embedded in Lucite for a memento. He looked at me a bit oddly and left, so… I guess not.

I’m interested to see that surgeons no longer slash you open to get at offending organs as they did when I had my appendectomy back in the Eisenhower administration. Nowadays they don’t slash, they poke, using a laparoscope to conduct “keyhole surgery.” I’m fine with it: no stitches to take out, no lifetime scar.

If I were a young surgeon, though, I think I’d find it worrying. With more and better devices like this and a couple of cycles of advances in AI, shall we still need human surgeons in 2043? Maybe law school was a better idea after all.

Reflections on the hospital experience:

- Overall very positive: A big, extremely complex organization managed with skill and efficiency. Nursing staff uniformly polite and helpful, not over-fussy about masks if you stay in your room.

- Major complaint: That damn fool open-down-the-back hospital gown that only a board-certified professional contortionist can lace up. Whoever designed that monstrosity should be in jail. If they want easy access to my back and bottom, why not give me some loose pajamas that I can drop at a moment’s notice?

- Minor complaint: Not enough morphine!

Footnote: The gall bladder is where the body stores gall, aka bile, before releasing it into the intestine. Bile/gall is of course my stock in trade as an opinion journalist. A reader has expressed concern that with my gall bladder gone, I may no longer have enough bile in storage to deal properly with the politicians and celebrities I mock.

Don’t worry, Sir. The doctors assure me that my liver will still produce plenty of bile.

Although, checking my storage closet, I see supplies of wormwood are running low …

Math Corner. Here’s a not-too-hard brainteaser for you. I was a bit surprised to see it listed among the Problems in the December 2022 issue of Mathematics Magazine, proposed by the Missouri State University Problem Solving Group in Springfield, MO.

The reason I was surprised is that this is somewhat of an old chestnut that I have seen on the Problems pages of math magazines before. It has good coverage on the internet if you feel like cheating, but you really shouldn’t, at least for the first part. It’s a nice 15-minute mental workout leading to some interesting arithmetical insights, with connections to graph theory and elsewhere.

(a) Arrange the numbers from 1 to 15 (inclusive) in a row so that the sum of any two adjacent numbers is a perfect square.

(b) Find the smallest positive integer n such that the integers from 1 to n can be arranged in a circle so that the sum of any two adjacent numbers is a perfect square. Justify your answer.

John Derbyshire writes an incredible amount on all sorts of subjects for all kinds of outlets. (This no longer includes National Review, whose editors had some kind of tantrum and fired him.) He is the author of We Are Doomed: Reclaiming Conservative Pessimism and several other books. He has had two books published by VDARE.com com: FROM THE DISSIDENT RIGHT (also available in Kindle) and FROM THE DISSIDENT RIGHT II: ESSAYS 2013.

For years he’s been podcasting at Radio Derb, now available at VDARE.com for no charge. His writings are archived at JohnDerbyshire.com.

Readers who wish to donate (tax deductible) funds specifically earmarked for John Derbyshire’s writings at VDARE.com can do so here.