03/17/2003

Published on VDARE.com — March 17, 2003

By Samuel L. Baker and Paul Craig Roberts

What has become of movie critics when they can only evaluate a film in terms of its political correctness?

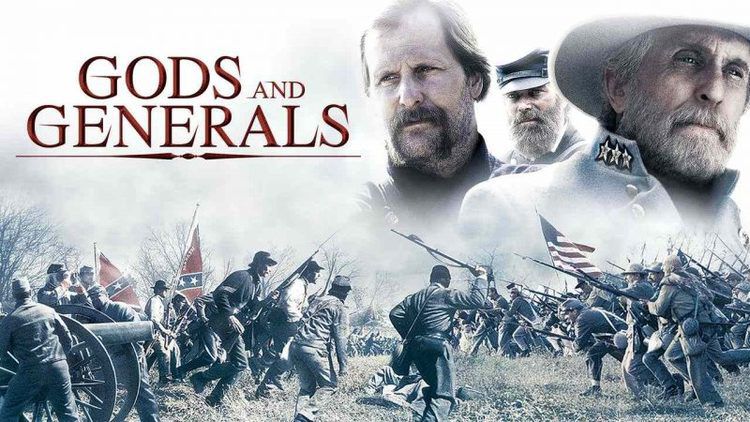

Ronald Maxwell’s film, "Gods and Generals," is the second in a War Between the States trilogy. The film is historically correct. But it is not politically correct. In reading the various reviews, one cannot avoid the conclusion that for movie critics only films that are politically correct are historically correct.

Southern Americans are supposed to be tyrants who abused their black slaves and fought a "Civil War" in order that they might keep on abusing them. These same racist Southerners continued to abuse blacks via the KKK and segregation long after the Moral North won the Civil War, fought for the sole purpose of freeing the slaves from the mean-spirited white supremacists of the Confederacy.

In contrast with this propaganda picture of the South, Maxwell’s film depicts Southerners as honorable and religious people whose loyalties are to their states. When Robert E. Lee turns down Lincoln’s offer as commander in chief of the Union army on the grounds that he cannot lead a military force to invade his homeland, he is embarrassed for the federal official who keeps telling him he is missing "a great career opportunity."

The film makes clear that Lincoln forced the war and was the aggressor against the South. Forced to defend itself, the South raises a citizen army. One of the stars of the Army of Northern Virginia is VMI professor Thomas Jackson, who earns the nickname "Stonewall" for his stand at Bull Run, the first major battle of the war. Throughout the movie, the modest and pious Jackson insists that the name properly belongs to his brigade, not to him.

"Gods and Generals" deals with three of the opening battles of the war, Bull Run, Fredericksburg, and Chancellorsville. Lee’s outnumbered and outgunned forces whip the Union army in all three encounters, thanks in part to the arrogance and incompetence of the Yankee generals. It is painful to watch utterly stupid Union generals send brigade after brigade to be slaughtered at Fredericksburg.

Fredericksburg was a portent of Grant’s strategy of exploiting his manpower to send wave after wave of Union troops to their deaths in order to exhaust the South’s supply of ammunition and wear down Lee’s undefeatable army.

The opening guns of Fredericksburg are also a portent of Sherman’s strategy of shelling towns containing not Confederate soldiers but women and children. The minute Union troops entered the town, they turned to looting, a practice that continued throughout the war.

Southerners and blacks, whether slave or free, are portrayed as having warm and respectful relationships. Although there were cruel exceptions, this relationship is historically accurate. When Lincoln declared the Emancipation Proclamation (which only applied to "rebel held territory") as a war measure in hopes of stirring up a slave rebellion, the stratagem failed. The blacks did not revolt despite the soft target of women and children left in charge on the plantations.

Truth, of course, is no defense against the charge of being politically incorrect. Film critics have worked overtime to demonize the film and its creators. Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun Times opens his review by saying, "Here is a Civil War movie that Trent Lott might enjoy." Among Ebert’s complaints is that in the film "slavery is not the issue." Apparently, Maxwell should have made a propaganda film like Leni Riefenstahl made for Hitler. Only the target would be different.

Orlando Sentinel movie critic Roger Moore writes "We… shake our heads at the historical revisionism." Moore believes proof of "revisionism" is found in the fact that "the ’s' word is hard to come by in this endless epic." When a Union officer moralizes on slavery in one scene, only then, according to Moore "is the ugly source of the struggle correctly articulated." Apparently, Moore didn’t hear the rest of the speech as the Union officer explicitly declared that slavery was not the cause of the war. This particularly Union officer was not prepared to fight for Lincoln’s cause of retaining the Southern tax base. He required a moral cause, and found his in his war against slavery.

Noting cameo appearances, Moore asks, "Surely there was a role for the least repentant Southern apologist of them all, Trent Lott?" It is a mystery that Moore sees Lott’s pandering as Southern apologetics, but then Moore is so historically ignorant that he complains that "Maxwell’s racial myopia is patronizing" and his film’s "general whitewashing of history is patronizing and wrong." He concludes, "Thankfully, it will be the PBS version of the war that will stick in the public mind."

Margaret A. McGurk of the Cincinnati Enquirer takes issue with the movie’s "vision of Jackson as a serene, kindly commander whose military prowess was the result of saintly religious faith." She states that "Historians may also squirm at the movie’s awkward bid to reconcile heroism and slavery, and insistence that sovereignty was the real issue — as if Confederate states seceded because they wanted to issue their own postage stamps." In McGurk we have a critic who is unaware that secession flowed from South Carolina’s refusal to collect the tariff that the Republicans used to bleed the South in order to protect their northern industries and fund their central government.

Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly describes the film as "crudely simplistic as an apologia for the Confederate ideology … When Jackson speaks of the need to defend his beloved Virginia against 'the triumph of commerce — the banks, factories,' the sentiment rings empty." He concludes, "As history, 'Gods and Generals' is a whitewash, literally; it takes pains to depict Jackson as the best friend a black cook ever had, as if that ameliorated the South’s treatment of slaves."

Sean O'Connell of filmcritic.com says "Whether intentional or not, Maxwell has crafted the most melodramatic piece of Southern propaganda since Gone With the Wind." The black actors, according to O'Connell, "supply exaggerated 'Uncle Tom' pitches to their dialogue."

Jonathan Foreman of the New York Post writes, "It’s so anxious to whitewash the Southern cause, it almost makes 'Gone With the Wind' look like a Spike Lee Joint." He goes on to say "The movie goes to great pains to stress that Southerners cared only about a constitutional theory — states' rights — and not about defending slavery. It’s a substitution of a dishonest folk history for real history."

Mick LaSalle of the San Francisco Chronicle shows his own ignorance of history when he writes, "If one were to watch the movie with no knowledge of history, one could be left with the impression that in 1861, a maniac named Lincoln decided to arm federal troops and attack neighboring states because he felt like it." But that is precisely what did happen. The only thing missing is the reason Lincoln "felt like it." Lincoln was unwilling for the union to dissolve, because it would cost him the tax base essential to his government-business schemes.

In general the critics believe that it is immoral of Maxwell to tell any part of the story from the South’s point of view, even if accurate. Critics insist that the South was evil. The true story, they protest, is one of evil stomped, looted, and burned out of the South by the moral righteousness of the North.

William Arnold of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer writes, "The filmmakers' decision to tell the story…mostly from the South’s point of view strips it of a moral perspective that’s easy to swallow."

Michael Wilmington of the Chicago Tribune believes that the film’s portrayal of "the Southern rebellion" as "a noble cause" was an unfortunate accident rather than writer-director Ronald Maxwell’s intention. Wilmington "hopes the TV version will correct the big flaw" and the Confederacy will be painted as black as it deserves.

Movie critics, alarmed at the lack of political correctness in "Gods and Generals," gave the movie bad ratings because of its ideological failings. These "critics" are not critics. They are ideologues and propagandists. They betray their occupation in order to indoctrinate. They are good little servants — slaves really — of the all-powerful state founded by Lincoln.

March 5, 2003

Samuel Baker [send him mail] is an engineering graduate of Auburn University. Dr. Roberts [send him mail] is John M. Olin Fellow at the Institute for Political Economy and Senior Research Fellow at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University. He is a former associate editor of the Wall Street Journal and a former assistant secretary of the U.S. Treasury. He is the co-author of The Tyranny of Good Intentions.

Copyright © 2003 LewRockwell.com