How Horrible Is The Arbery/McMichael Verdict? HORRIBLE, For All White Americans

By Jared Taylor

11/26/2021

After Kyle Rittenhouse was found to have acted in self-defense during the riots in Kenosha, Wisconsin, there was some hope that the three defendants in the Arbery case might be acquitted. There are similarities: Mr. Rittenhouse shot the first man, Joseph Rosenbaum, when he lunged and tried to take away Mr. Rittenhouse’s rifle.

The shaky, incomplete video of Arbery’s death shows something similar. Travis McMichael does not fire until Arbery appears to run right into him and tries to take away his shotgun. The greatest difference, of course, is what led up to the moment when Rosenbaum and Arbery each closed on armed men and tried to wrestle away their weapons. An almost identical three-second encounter led to an acquittal in one case and life in prison for the other.

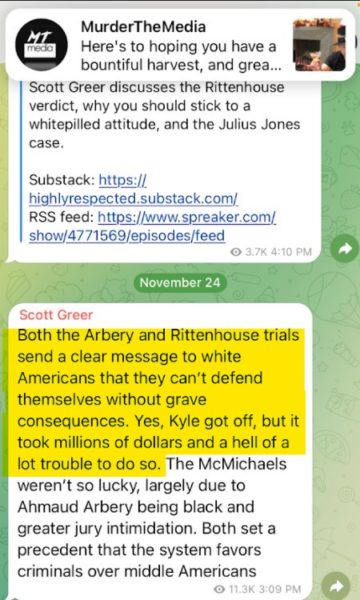

Scott Greer, popular on Twitter and Telegram, reflected the dismay of many when he wrote:

Both the Arbery and Rittenhouse trials send a clear message to white Americans that they can’t defend themselves without grave consequences. Yes, Kyle got off, but it took millions of dollars and a hell of a lot of trouble to do so.

Mr. Greer’s gloomy conclusion might be even more justified if he had cited the verdicts in the case against the participants in the 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia. In Sines v. Kessler, indigent defendants had to contend with “expert witnesses” hired by the plaintiffs to explain what their words had really meant, and were found guilty of conspiring — sometimes with people they didn’t even know — to violate the rights of Charlottesville residents and to commit racial violence.

The outcome of the Arbery case is shocking: unless the verdicts are somehow overturned, all three defendants will spend at least 30 years and perhaps life in prison. Travis McMichael, 35, who pulled the trigger, is guilty of “malice murder” — the Georgia equivalent of first-degree, premeditated murder. The law says malice is assumed when “no considerable provocation appears and where all the circumstances of the killing show an abandoned and malignant heart.” His father Gregory is guilty of “felony murder,” which is a lesser charge, but carries the same penalty: a minimum of 30 years and possible life. William “Roddie” Bryan, who followed in his own vehicle and took the video, is also guilty of “felony murder.”

At sentencing, Judge Timothy Walmsley will decide only one thing: whether to put the men away for life or let them apply for parole 30 years or more from now. My prediction is that Travis, the actual killer, will get life, and the others will be eligible for parole in 30 years. This means Gregory, age 65, will almost certainly die in prison, and Mr. Bryan, age 52, will be an old man if he ever gets out.

Needless to say, a crucial difference in the Rittenhouse and Arbery cases is race. Blacks insisted noisily that Arbery was killed for “jogging while black,” and a full examination of the case can lead to only one conclusion: race worked dramatically against the defendants.

Undisputed Facts

Travis McMichael recounted the facts in his testimony, and they are largely unchallenged. Satilla Shores, where the defendants lived, had seen a sharp rise in thefts and other petty crime to the point that residents began installing surveillance cameras and stopped letting children play outside after dark. There was a Facebook group where people posted accounts of crime, which became a common subject of neighborhood conversation.

A house was under construction just a few doors down from where the McMichaels lived. Neighbors told the absentee owner they had seen people prowling through the building, even at night. He installed security cameras that caught Ahmaud Arbery inside the building poking around no fewer than five times in the months before the incident, usually at night. The owner shared the videos with neighbors, who began to wonder if the man in the videos might be the person stealing things in the neighborhood.

Twelve days before the shooting, Travis was driving at night when he saw Arbery “creeping in the shadows” around the building. He parked and shined lights on Arbery, who disappeared into the house. Travis says Arbery reached for his waistband as if he might be carrying a gun. Travis went home, armed himself, and called the police. An officer arrived and, together with other armed neighbors, looked though the property but found no one. The officer thanked the men for being on alert, and did not criticize them for carrying weapons.

On February 23, 2020, during the day, Arbery was again in the building and realized he had been spotted by a neighbor.

Arbery on surveillance camera on the day he was shot, before he was spotted by a neighbor and ran away.

He sprinted out of the building past Gregory McMichael, who was working in his front yard. Gregory went into the house and told his son Travis, who also lived there, to grab a weapon, get in their pickup, and chase Arbery.

As they drove off, Travis asked if his father had called 911, but Gregory was trying to fit himself uncomfortably into a child-safety seat on the passenger side and did not answer coherently. Travis testified that he mistakenly thought his father had called the police.

The two followed Arbery for about five minutes, several times getting close enough to say such things as “Stop. We want to talk to you.” Arbery said nothing and kept running. At one point, another neighbor, William “Roddie” Bryan, joined the chase in a black pickup, but Travis, who was driving, did not know Mr. Bryan, and had no idea why this other vehicle was driving close to Arbery. On the witness stand, he said he thought Arbery, who could be armed, might be trying to hijack the black pickup.

Travis testified that he gave up trying to catch Arbery and stopped the truck so that his father could get out of the uncomfortable child seat and climb into the truck bed. He drove slowly to a crossroads so they could see which way Arbery might run, in order to tell the police when they arrived.

Travis wondered why the police were taking so long, and again asked if his father had called 911. Only then did he learn that his father had not made the call. Travis then dialed 911 but handed the phone to his father, standing in the bed of the truck, when he noticed Arbery running towards him.

As Arbery approached, Travis took the shotgun out of the car and stood with it in “port arms” position, with the weapon diagonally across his body, barrel pointing up. This would have been the first time Arbery saw a weapon. Travis had spent nine years in the Coast Guard, where he had been a “boarding officer,” or maritime police officer. He had weapons training, in which it was procedure to display a weapon to assert authority. He had also practiced hand-to-hand combat, in which it was an officer’s duty never to lose control of his weapon, which could be turned against him.

Travis stood by the open driver’s-side door as Arbery ran towards him. As he said on the stand and as is visible in the video, there were unfenced, open yards on both sides of the road. Arbery could have run off the road at any time or stayed on the road and run straight past Travis on the passenger side with the pickup between the two.

Gregory was standing in the bed of the truck as Arbery ran up. He had finished the 911 call and held a pistol in his hand. Arbery did not run off the road or simply run past the truck. Although the video wavers away briefly, he clearly cut sharply to the left across the front of the truck, straight at Travis, attacked him and tried to take away the shotgun. It was only then, and as Arbery continued to grapple for the gun, that Travis fired three times, killing Arbery. Travis testified that he believed he was in a kill-or-be-killed fight.

The police arrived soon after and found Travis in a state of shock. He was splashed with blood from his close encounter with Arbery.

When an officer asked if he was alright, he replied, “I’m not alright.” Police bodycam footage shows Gregory comforting his son, telling him, “You had no choice.”

Gregory comforts Travis. Arbery’s body is visible in the foreground.

A neighbor testified that when she drove past the scene shortly after, Travis was pacing with his hands on his head, obviously upset.

One of the first prosecutors on the case, George Barnhill, wrote a report, well worth reading in full, that the defense surprisingly never referred to and that has been all but forgotten. It concludes that the three men were trying to make a legal citizen’s arrest, were legally armed, and had probable cause to believe Arbery had committed a burglary. Mr. Barnhill wrote: “Given the fact Arbery initiated the fight, at the point Arbery grabbed the shotgun, under Georgia law, McMichael was allowed to use deadly force to protect himself.” His conclusion: “We do not see grounds for an arrest of any of the three parties.” He probably thought it was unnecessary to add the obvious: that if the men had wanted to kill Arbery rather than stop and talk to a man they thought might be armed, they could have done so as they drove close to him. Or that people who are about to commit a murder do not call 911 or make a video that they immediately turn over to the police. Mr. Barnhill based his report not just on interviews but also on the Bryan video, which was not made public until later.

What the jury never heard

In pretrial motions, Judge Walmsley ruled on which evidence was admissible. The defense wanted to tell the jury about Arbery’s medical and arrests records. Arbery had been diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder after a June 2018 incident in which his mother, Wanda Cooper, had called the police on him. She warned the dispatcher that the responding officer should be careful because Arbery would become violent if the police were confrontational. A different 2017 encounter with police that was caught on video certainly suggests he was volatile.

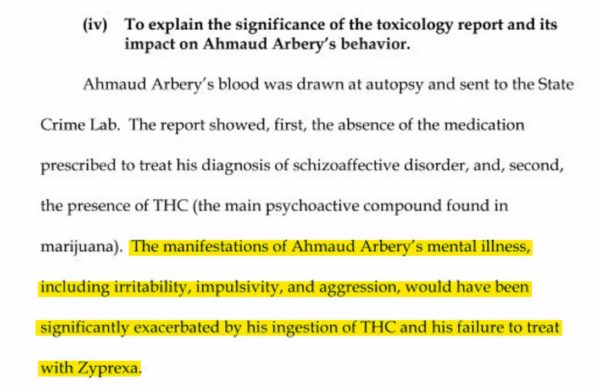

Arbery was put on Zyprexa, an anti-psychotic drug used to treat schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. The toxicology report from the autopsy found that Arbery had not been taking Zyprexa, and that there was a small amount of THC in his body. The defense wanted to present this report to the jury because it is known that THC makes people with Arbery’s form of mental illness more aggressive.

The prosecution argued that “why Mr. Arbery did anything he did is completely irrelevant. The question is about what the defendants did, and they knew nothing about what was in his system.” The judge ruled the toxicology report inadmissible.

The defense also wanted to introduce Arbery’s criminal record. In 2013, he brought a handgun to school and ran away from police who tried to arrest him. There is a video record of a 2017 arrest for trying to shoplift a television. In the two years before his death, he became known to convenience-store owners as “The Jogger,” who would stop outside, do stretching exercises, then come into the store, steal merchandize, and run away.

At the time of his death, Arbery was on probation for two crimes. This probably made him less willing to stop and talk with the McMichaels, but Judge Walmsley ruled that prior convictions were irrelevant.

The judge also excluded prosecution evidence. In a statement to police, Mr. Bryan, who was following in his black pickup and who had made the video, said that Gregory McMichael had referred to Arbery as a “fu**ing ni**er” shortly after the shooting. Mr. Bryan did not testify, so he could not be examined on that point, and the judge disallowed admission of this evidence by any other means.

The judge also refused to let the prosecution cite allegedly racist text messages from Mr. Bryan’s cell phone. During a bond hearing more than a year ago, prosecutors said the text messages contained “a ton of filth.” The judge did, however, allow police bodycam footage that showed Travis McMichael’s truck from the front, showing a Confederate-flag license plate.

The Trial

Jury selection took an agonizing 13 days (the Rittenhouse jury was chosen in one day). One thousand potential jurors were called, but only half showed up. This is because unlike in most trials, the summons explained that this was the Arbery case, and many people did not want to serve.

During jury selection, a group of blacks from a non-profit called the Transformative Justice Coalition (TJC) was constantly inside and outside the courthouse. On the first day, they sat all day on folding chairs outside the courthouse, while some watched inside. They carried signs that said “Justice for Ahmaud,” and marched from the courthouse to a mural of Ahmaud Arbery a few blocks away. On the second day, they took a bus to Satilla Shores and protested in front of houses on the street where Arbery died.

Mr. Bryan’s lawyer, Kevin Gough, complained that demonstrators visible to potential jurors were intimidating. He also noted that Lee Merritt, the lawyer representing Arbery’s mother Wanda Cooper in a civil case, was trying to teach people how to manipulate jury selection. Mr. Merritt’s blue-checked Instagram account had a now-deleted message that said: “Register to vote. Show up for jury duty. Remember this phrase ‘I can be fair.’ “ Jurors with apparent bias may be allowed to serve if they assure the court that they can be fair.

Throughout the trial, blacks occupied the area in front of the courthouse. The demonstrations were mostly praying and shouting, but on at least one occasion, a black militia including members of the New Black Panther Party swaggered around with guns.

Al Sharpton sat with Arbery’s parents during testimony, prompting Mr. Bryan’s lawyer, Kevin Gough, to object. “We have had civil rights icons sitting in here,” he said, “in what the civil rights community contends is a ‘test case for civil rights in the United States,’ eyeballing these jurors.” He wanted to know: “Which pastor is next? Is Raphael Warnock [a black preacher recently elected to the Senate from Georgia] going to be the next person appearing?”

Mr. Gough reminded the judge of precedents from mafia trials, in which judges kept mob bosses out of the gallery because their presence could intimidate jurors and witnesses. The judge refused to bar anyone from the courtroom and Mr. Sharpton later told reporters that Mr. Gough had shown “basic bias — the same bias that killed Ahmaud Arbery.” After Mr. Gough said he didn’t want “any more black pastors” in the courtroom, hundreds tuned up to pray on the courthouse steps. On one occasion, Al Sharpton, Jesse Jackson, and Martin Luther King III led a rally as testimony continued.

Jesse Jackson also sat in court with Arbery’s family. When Wanda Cooper began to sob loudly, Mr. Jackson put his arm around her in view of the jury. Mr. Gough moved for a mistrial. “We contend that the atmosphere for the trial, both inside and outside the courtroom, at this point, has deprived [my client] Mr. Bryan of the right to a fair trial,” he said, adding that daily rallies by the “left woke mob” were the equivalent of a “public lynching.” His motion was denied.

Would Judge Walmsley have let robed Klansmen rally for “justice for the McMichaels” day after day? Would he have let young men in matching khakis and white polo shirts sit in the gallery?

Legal issues

A crucial legal question was whether the three defendants were trying to make a lawful citizen’s arrest. The relevant law is only two sentences long:

A private person may arrest an offender if the offense is committed in his presence or within his immediate knowledge. If the offense is a felony and the offender is escaping or attempting to escape, a private person may arrest him upon reasonable and probable grounds of suspicion.

In an independent analysis of the case, lawyer Andrew Branca argues that the two sentences anticipate two different scenarios. The first sentence is about minor offenses, such as shoplifting; citizens may not step in unless the crime was “committed in their presence or immediate knowledge.” In the case of a felony, a citizen can act on “reasonable and probable grounds.” Prosecutor Linda Dunikoski tried to combine the two sentences, insisting that the crime for which citizens could make an arrest had to be a felony committed “in their presence.” She noted that trespassing — the only crime of which Arbery is known to the defendants to have been committed — did not justify citizen’s arrest, claiming that detention was lawful only in “emergency situations” when a crime is happening “right then and there.”

Mr. Branca notes that when a law is ambiguous it must, under the doctrine of “lenity,” be interpreted in the favor of a defendant, which would mean the men had the right to arrest Arbery merely for trespassing. Judge Walmsley did not clear up the ambiguity, and seemed to side with Miss Dunikoski, telling the jury that anyone who is the target of an unjustified citizen’s arrest “has the right to resist the arrest with such force as is reasonably necessary.”

Miss Dunikoski followed up this advantage: “You [Travis McMichael] can’t claim self-defense if you are the unjustified aggressor,” she said. “Who started this? It wasn’t Ahmaud Arbery.” Clearly, it is absurd to say that Travis McMichael forfeited all rights to self-defense. Was he legally obliged to let Arbery beat him to death? No matter what led up to the fight over the shotgun, at some point is could be reasonable to see Arbery as the aggressor. The jurors have not explained their verdict, but if they accepted the prosecution’s argument, there was never any hope for an acquittal.

In her closing arguments, Miss Dunikoski made the outrageous claim that the defendants chased Arbery “because he was a black man running down the street.” There had been no testimony to suggest race had anything to do with the decision to give chase, and it is impossible to believe the McMichaels would have jumped into their truck if Arbery had just been “a black man running down the street.”

Verdicts

These defendants have seen one of the most dramatic courtroom reversals imaginable. The original prosecutor saw no reason to charge them with anything; now Travis McMichael will spend the rest of his life in prison. Despite all the ambiguities and extenuating circumstances in his cases, he is guilty of the same crime — malice murder — that he would have committed if he had deliberately chased down and murdered an unknown black man who was jogging by. The only difference is that if there were evidence he had done that, the prosecutor would probably have called for the death penalty.

Gregory McMichael and William Bryan will grow old in prison and may well die there. But why are they guilty of felony murder? Georgia has a very broad concept of who is “party to a crime.” If you help anyone who commits murder, you can be charged as the principle offender. Under Georgia law, a defendant is guilty of felony murder if, “in the commission of a felony, he or she causes the death of another human being irrespective of malice.” The jury found the two men guilty of two felonies, aggravated assault and false imprisonment. They used their pickup trucks to try to cut Arbery off and box him in. The indictment says motor vehicles “when used offensively against a person are likely to result in serious bodily injury,” so this was aggravated assault. By illegally trying to hold him against his will they committed false imprisonment.

Gregory McMichael was not even driving. William Bryan probably did not know anyone in the truck ahead was armed, much less that Arbery would be shot to death. Prosecutors say that at the sentencing hearing they will seek life in prison with no possibility of parole for all three men.

It is impossible to imagine this kind of vindictiveness if Arbery had been white. Just as in Derek Chauvin’s trial for the death of George Floyd, there is no evidence that race had anything to do with the defendants’ actions. It is true that Gregory McMichael may have referred to Arbery as a “fu**ing ni**er” shortly after his death. Did that show a racial motive or was it an emotional outburst about a man he believed had provoked his son to the point of taking someone’s life?

All three men have also been charged with federal hate crimes, and are scheduled to go on trial in February. Absurdly, the McMichaels also face federal charges of “using, carrying, brandishing and discharging a firearm during and in relation to a crime of violence.” Arbery’s mother Wanda Cooper has filed a multi-million dollar suit against the three men and various officials who first handled the case, accusing them all of “racial bias, animus, discrimination,” among other things.

Reactions

Blacks are, of course, delighted by the verdicts. When they were announced, a crowd of about 60 marched around the courthouse shouting “No justice, no peace” and “Whose streets? Our streets!” These are expressions of intimidation and even vigilante intent, not an appreciation of impartial justice. John Perry, former head of the local NAACP said that acquittal would have been unacceptable. He predicted “easily 10,000 people gathering here.” Any juror — their names have not been made public — who voted to convict for fear of mob violence is no doubt patting himself on the back.

I know of no public figure who has denounced the verdicts. President Biden said the justice system had done its job; earlier he said Arbery’s death “is a devastating reminder of how far we have to go in the fight for racial justice in this country.” Gov. Brian Kemp of Georgia said Arbery “was the victim of a vigilantism that has no place in Georgia,” and hoped for “healing and reconciliation.” Sen. Raphael Warnock called the verdict “accountability” but not “true justice,” adding ridiculously that real justice “looks like a black man not having to worry about being harmed — or killed — while on a jog.”

Even Florida defense lawyer Mark O’Mara, who — in what now seems a miracle — got an innocent verdict for George Zimmerman, says these men are guilty because they were the aggressors. He says pointing a shotgun at someone is aggravated assault. From the video, it is not clear whether Travis ever did point his weapon at Arbery, who may well have grabbed it from port arms when he charged. Why was Mr. Zimmerman not the “aggressor” when he approached Martin in the same spirit in which the three defendants approached Arbery? Or when he drew his pistol on an unarmed attacker?

One of the strangest aspects of this case is the role of the Bryan video. Two days after the verdict, NBC News published an indignant article called “They Nearly Got Away With It.” It noted that the three men were not arrested until two and a half months after the shooting, and only after the video was “leaked.” It was not leaked. In consultation with his lawyer, Gregory McMichael gave the video to a radio station in the hope that its release would put down rumors among blacks that his son had done something wrong. He thought it would settle any questions about what provoked the shooting!

Public and media opinion appear to be unanimous: the video proves that the defendants were essentially a lynch mob, and that they were indicted only because this devastating evidence came to light. On the contrary, the video is perfectly consistent with Travis McMichael’s initial statements to the police, his testimony at trial, and District Attorney Michal Barnhill’s decision not to bring charges. To see in that video evidence for malice murder — of “an abandoned and malignant heart” — is to see something that isn’t there. This stark divide in how people interpret the very same images is just one more example of how race has enflamed the American mind.

The reaction to the video’s release was something akin to panic in Georgia. The state promptly passed its first hate-crime law — even though there is no evidence race played any role in the case. The legislature also repealed the citizen’s arrest law. At the signing ceremony for the repeal, Governor Brian Kemp said, Georgia was “the first state in the country to repeal its citizen’s arrest statute,” adding, “Today we are replacing a Civil War-era law, ripe for abuse.” Is any Civil War-era bill ripe for abuse?

The new law forbids citizen’s arrest except for store employees who hold shoplifters for the police, and restaurant personnel who stop anyone trying to leave without paying. Georgians can still use deadly force to protect life, but if they stop a burglary, car theft, or even arson (except to protect a residence), they will be criminals.

If Georgians were going to tinker with legislation, might they have reconsidered a law that could land a man in prison for life for trying to head off a man he thought was a fleeing criminal who was then shot by someone he didn’t even know was armed? The injustice of this seems to have occurred to no one. If the law was to be changed, it was strictly to inculpate these three men.

The defense will appeal on grounds of jury intimidation, prejudicial instructions to the jury, admission of evidence, and probably other grounds. What are the chances of an appeals court infuriating the entire media/political establishment and ordering a retrial? Zero. In a case like this, racial hysteria makes impartial justice impossible. Probably the only forlorn hope these men have is that a decade or two from now, the racial climate will have changed to the point that a governor or president might grant clemency.

If that ever happens, they will have to turn over every dime they ever make to satisfy the crushing damages Wanda Cooper will surely win in her civil suit.

Jared Taylor is the editor of American Renaissance. You can follow him on Parler and Gab.