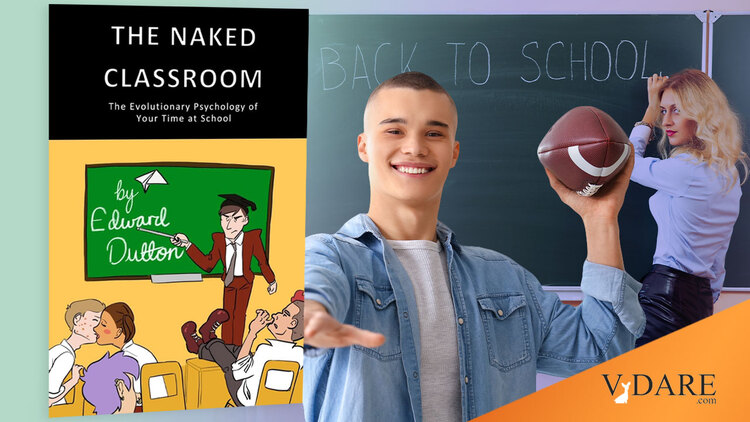

New Dutton Book, THE NAKED CLASSROOM: THE EVOLUTIONARY PSYCHOLOGY OF YOUR TIME AT SCHOOL, Explains Why Science Answers Everything

12/09/2023

Science should be the most fascinating of subjects at school. Humans are an advanced form of ape and, as a consequence, biology is the ultimate explanation for everything we do. Why are the most racially diverse cities in the United States are also the most racially segregated? [Surely, Liberals Should Support White Nationalism, by Noah Carl, Aporia Magazine, November 19, 2023]. Why are scientific geniuses and other major innovators overwhelmingly men, as I explored in my book The Genius Famine? Why, when you were at school, did you notice that boys preferred science and rough games based around competition? Biology is the ultimate explanation for everything we do and can answer all those questions.

In my new book The Naked Classroom: The Evolutionary Psychology of Your Time at School, I show that science answers the kinds of questions you didn’t dare ask at school. Why are the black kids so talented at sprinting, but not so much when it comes to mathematics? Why do the “special” children look physically unusual? Why is the young woman teacher — who teaches a humanities subject such as history — having sex with that “jock” rather than the boys who enjoy her subject? In The Naked Classroom (a nod to zoologist Desmond Morris’ book The Naked Ape), I provide the scientific answers to these questions and many more.

I have written many articles for VDARE.com on “based science,” meaning empirically accurate scientific research that is suppressed by our ideologically woke universities because it questions their dogmas in relation to such “controversial” issues as race, gender and sexuality. On a number of stories, such as my piece about Roman genetics, editors asked me to explain terms such as “correlation” and “statistical significance” because most readers are people like me. They are “humanities people.” Most journalists and politicians fall into this category, tending to study subjects such as law and philosophy at university. Only one prime minister who led my country, England, had a science degree: Margaret Thatcher studied chemistry. Only one American president, Jimmy Carter, had a science degree.

As I explain in the book, when I was at school, I quickly concluded that I did not like science. I was a humanities person. Growing up in England, with its castles and so many ancient buildings, fascinating history was all around me. Religion studies were manifestly relevant because we prayed and sang hymns at school. I enjoyed reading, so English was important. I could even cope with geography, especially human geography and questions about why people migrate. By contrast, the details of how flowers reproduce, why magnesium reacts with oxygen, or the relationship between time, speed, and distance simply didn’t capture my youthful imagination.

They might have if the relevance of science to the subjects that interested me, or even more important, to understanding life, was made clear. There is a hierarchy of subjects. Biologist E.O. Wilson called it “consilience.” Assertions in history must make sense in terms of human psychology, and these must be reducible to biology, and these must be reducible to chemistry. But, unfortunately, these subjects have broken up and separated into specialties that have little to do with each other and this is especially true of the divide between science and the humanities. I often found material in the humanities very unsatisfying and question-begging. Why did people suddenly lose confidence resulting in the Wall Street Crash? Why, if being religious is linked to the environment, do some people subject to the same environment end up not being religious?

I knew I had to do well in science at school even to study a humanities subject at university. I did well, but to my subsequent regret, I dropped science as soon as I could at 16, and focused on the humanities, eventually pursuing degrees in theology. Under this regime, all explanations for everything were purely environmental and there was no engagement with the scientific study of religion at all. I only realized the importance of biology to making sense of religion — why some people are religious and others aren’t — when I had already finished my doctorate in Religious Studies in my mid-20s and found Wilson’s work.

More recently, if only they had taught science in a way that was directly relevant to my life and to the humanities, which I actually liked, then my life could have been so different. In The Naked Classroom, I try to demonstrate why biology and evolution are, or were, relevant to one’s time at school.

In a brief summary like this, I can perhaps give some of the personal examples I explore in the book. At my primary (elementary) school, a number of the “special” children were unusual looking. They were not only mildly retarded but also had unusual, distinctive facial features. Why? Answer: When fetal development goes awry, mental capability and physical appearance are affected, meaning what one’s brain is like is linked to what one looks like. Many of these children likely had fetal alcohol syndrome.

At my secondary (high) school, two women teachers — both in the humanities, predictably — left at the end of a school year because they had sex with 16-year-old pupils. How could this happen? Well, it’s an evolutionary mismatch for women in their mid-20s to spend vast amounts of unsupervised time together with 16-year-old boys. It was most uncommon in our culture until quite recently and the result is predictable.

Why are so many male teachers homosexuals? Why is serious bullying such an intractable problem at schools — especially at girls’ schools? Why are teachers so left wing? Why has anorexia been displaced by Sudden Onset Gender Dysphoria among teenage schoolgirls? I hope to have answered these questions, and many more, and in so doing persuaded you “humanities types,” like me, that science need not be dull. Science, if taught in a “based” way — based in everyday life — can make sense of almost everything, from race differences in sporting ability to even how corporal punishment was traditionally administered at schools.

Edward Dutton (email him | Tweet him) is Professor of Evolutionary Psychology at Asbiro University, Łódź, Poland. You can see him on his Jolly Heretic video channels on YouTube and Bitchute. His books are available on his home page here.