11/06/2009

(First appeared in Forbes, Sept 22, 1997)

[Peter Brimelow writes: We just found my article on the economist Gordon Tullock, published in the dead-tree version of Forbes Magazine in the pre-internet Dark Ages. Tullock has a remarkably fertile mind, very like (in this respect at least) Milton Friedman and I hoped to begin a series of annual interviews with him, as I already had with Friedman. But both projects were victims of the retirement of the great Forbes editor Jim Michaels: his successor, Bill Baldwin, said (or more probably echoed the advertising salesmens' knee-jerk opinion) that we had to find younger economists.

Tullock’s concept of rent-seeking is more than ever relevant in the age of Obama — as is his view, as a trained Sinologist, that China, now even more lauded as the engine of the global economy, might well return to despotism, or even break up completely.]

WHAT DO THESE PICTURES have in common?

"Lobbying has become Washington, D.C.’s largest private employer … . There are 125 people working to influence government policy for every member of Congress, up from 31 lobbyists per congressman in 1964."

— From "Washington’s Lobbying Industry: A Case for Tax Reform," a memorandum prepared by the office of House majority leader (and Ph.D. economist) Dick Armey (R-Tex.)

"In 1989 we had essentially no compliance function. Then we hired our first compliance officer. He hired a staff of half a dozen. The whole focus changed from building the business to papering the files. Of course, when there was a [Securities & Exchange Commission] audit, he was a local hero. But it was of no benefit to the clients. We never had any intent to deceive them. And if we had, we could still have done it. He [the compliance manager] became a partner. I left."

— Disgruntled Wall Street money manager

"I signed the Family Leave Act; it was my very first bill. And I’m proud of it because it symbolizes what I think we ought to be doing … . [It] has let 12 million families take a little time off for the birth of a child or a family illness without losing their job. … I never go anywhere, it seems like, where I don’t meet somebody who’s benefited from the Family Leave Law. In Longview, Tex. the other day I met a woman who was almost in tears because she had been able to keep her job while spending time with her husband, who had cancer."

Bill Clinton, in second presidential debate, Oct. 16, 1996

Answer: They all involve what economists call "rent-seeking" — the use of political or institutional power to extract "rent" (essentially, unavoidable payments) from the rest of the economy.

("Rent-seeking — it’s a terrible name," says economist David Henderson of the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, Calif. Henderson speculates that the name’s repellent clunkiness may have delayed general recognition that rent-seeking, parasitic and pervasive, is a fundamental economic reality in the modern world. His suggestion: "privilege-seeking." Hey, these are economists, not poets.)

Whatever its name, this is how rent-seeking works:

The Washington lobbyists are public-sector rent-seekers. They are being paid to extract rents by influencing legislation on behalf of their corporate clients.

And they succeed. One example from Congressman Armey’s collection: Sugar import quotas raise the price American consumers pay for sweeteners by about $1.4 billion annually. This benefits a remarkably small number of sugar producers and processors. One family alone, the Fanjuls of Osceola Farms, Fla., earns an estimated $65 million annually in artificial profits because its lobbyists have persuaded Congress to make it possible for the family to sell sugar at more than its natural market price.

The empire-building Wall Street compliance bureaucrat is a private-sector rent-seeker. He is diverting profits earned by the firm’s productive activities to himself and his empire.

Note, though, that he is able to do so because of a sort of tacit alliance with the public-sector regulators. They make his job necessary.

The First Rent-Seeker was congratulating himself on a newly popular subcategory of rent-seeking: so-called mandated benefits. The government uses political power to extract rents from the general public. Then it directs them to favored constituencies. The numbers can be very large: The Society for Human Resource Management estimated in 1989 that the Family Leave Act — no matter how nice a thought — would still cost nearly $440 million a year.

The government is still in effect buying votes with other people’s money. But rent-seeking — in this case rent-giving — tactfully avoids the need to raise the money first through taxation, which often causes such distress. Employers and, ultimately, all consumers pay. A (relatively small) class of employees benefit. Plus, of course, the politicians. They can crow about how "caring" they are.

Rent-seeking matters — a lot. Its cost to society is not just the rents transferred but also "rent-avoidance" — resources expended in trying to repel efforts to extract rents, for example, by hiring your own lobbyists. As Gretchen Morgenson showed in our last issue (Sept. 8), any business that neglects to hire a lobbyist is likely to become a victim of other rent-seekers who do have lobbyists.

Surprisingly, however, the realization that rent-seeking exists dawned on economists only quite recently. Too bad, because it’s a valuable concept that helps us understand what the politicians are doing to us when they say they feel our pain and offer to assuage it.

The father of the rent-seeking concept is Gordon Tullock, a quizzical, quirky, somewhat owlish 75-year-old professor of economics and political science at the University of Arizona in Tucson. Tullock was long associated with Nobel economics laureate James M. Buchanan, now at Virginia’s George Mason University, in the development of what is now called "Public Choice Theory," the application of economic analysis to political and governmental action.

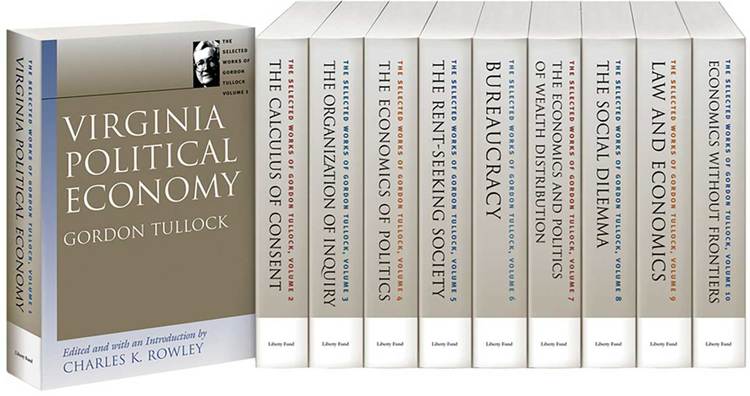

Many observers were surprised that Tullock was not included in the Nobel Prize Buchanan received in 1986. The omission was particularly striking since Buchanan and Tullock had actually coauthored the classic public choice text, The Calculus of Consent (1962). Speculation continues that Tullock will eventually win a separate Nobel Prize for his work on rent-seeking. In January 1998 he will be made a Distinguished Fellow of the American Economics Association. ("A plaque — no money," he says.)

Tullock was not trained as an economist — and beneficially, he argues with characteristic wryness. This, he argues, is an advantage in understanding economics. (He compares the economics profession’s current preference for abstract mathematics to the drift from science to theology in classical Alexandria — and suggests that its function is merely to avoid political conflicts with noneconomists in the faculty lounge.) In 1947, after three years' wartime service as an infantryman, Tullock took a J.D. degree in a University of Chicago Law School accelerated program. He has no bachelor’s degree because, in a decision possibly reflecting his Scottish heritage, he declined to pay the required $5 fee.

Tullock then joined the State Department and was posted to the Chinese city of Tianjin. He observed the city’s fall to the Communists in 1949 and began his study of monetary cycles amid the disastrous inflation accompanying the Chinese Nationalist collapse. Thereafter, he was seconded to Yale and Cornell for three academic years to study Chinese. He notes gleefully that by reading Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises' Human Action in his spare time during this period, he found himself in key respects better prepared technically than an economics Ph.D. contemporary.

It is universally agreed that Tullock does not have a diplomat’s temperament. He eventually resigned from the State Department. In 1959, while a post-doctoral fellow at the University of Virginia’s economics department, he began working with Buchanan on what became The Calculus of Consent.

In 1987 Tullock moved to his present post in Arizona. A lifelong bachelor, he spends holidays with his sister’s family in Iowa. In an unusual departure for an academic economist, he is a major stockholder ("best investment I ever made") and longtime director of the family’s Dodger Co., a small Iowa-based firm that makes sports clothing, and its Whink, Inc., which makes industrial cleaners. He says this experience contributed greatly to his education in economics.

Tullock’s stint in China was crucial to his rent-seeking insight:

"See, you go into these cultures where people have produced just immense cultural achievements but are living in bitter poverty, and you discover very quickly they have a dominant government and the government is corrupt. Conventionally, economists have argued that a corrupt government doesn’t really cost anything because the man who receives the bribe gains what the man who pays the bribe loses. Well, you can’t really believe that if you're in China."

Similarly, Tullock points out, China provided the evidence for a key early effort by Anne Krueger — now an economics professor at Stanford University — to quantify his insight. (Krueger must also take the blame for coining the term "rent-seeking.") Krueger had estimated that the cost to Turkey and India of the bribes necessary to get around their various regulations amounted to 7% to 15% of GNP. This cost was not simply the expense of the bribe, but also the resources wasted by individuals in acquiring otherwise useless credentials and intriguing for appointments in the appropriate government bureaucracy.

Every major economics journal rejected "The Welfare Costs of Tariffs, Monopolies and Theft," Tullock’s original article on rent-seeking. It was finally published three years later, in 1967, in the Western Economic Journal, then new and little-read.

As an intellectual pioneer, Tullock is a connoisseur of such rejections. (He began his 1980 presidential address to the Southern Economics Association by celebrating the fact that the association’s journal would be compelled to publish it, after years of rejecting his submissions.) He savors the irony that because a standard textbook quickly picked up his rent-seeking concept, "there was a period when a lot of brand-new elementary [economics] students knew about it and no one else did."

Tullock’s serene but somber conclusions on the inefficient nature of the intellectual market: "The safe article for the young academic is one that makes a short, sound step forward in a well-established direction."

Sounds like good advice.

But it’s advice that Tullock himself — author of 15 books (the sixteenth, On Voting: An Introduction to Public Choice, due January 1998) and over 150 papers, on subjects ranging from game theory to "The Coal Tit As Careful Shopper," part of his little-known, but highly respected, contribution to biological theory — has somehow never quite gotten around to taking.

RELATED ARTICLE: WHITHER CHINA?

Why did China, long the world’s most advanced civilization, stagnate?

Gordon Tullock’s answers are typically offbeat. "You hear about these dynasties in China that last three or four centuries," he says. "But the overwhelming majority lasted only around 50 years. The prospect is that that will turn out to be the case here."

Tullock gives equal odds to three scenarios for China. "Economic growth and liberalization may continue — that’s not impossible," he says. "But it is quite out of the Chinese tradition. Mencius [Confucius' principal disciple, 3rd century B.C.] said the government should own the principal industries and closely control the rest. Even now, the big companies are still government run. It [the government] apparently doesn’t dare get rid of them."

Tullock’s second alternative: "It’s also possible that the government itself may abandon the move to free enterprise," he says. "China may come under the control of a set of old-fashioned Communists who clamp down the roof and stagnate." China has regressed like this before, Tullock notes: The Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) turned away from commerce and paper money.

Tullock’s third and most startling scenario: China might simply break up. "The area has had a more or less homogenous culture for about 2,000 years and a strong central government during maybe 1,500 of them," he says. "But it has broken up from time to time. The most recent case was in 1911. From 1911 to 1949 there was never any real central government in China." (See maps.)

Historic China, homeland of the Han Chinese, is only about half the area of the current People’s Republic, Tullock points out. Outlying areas like Manchuria, Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang and Tibet were added by imperial conquest. Their ethnic minority populations have a long history of periodic revolt. Even Taiwan, now the base of the Nationalist Republic of China, was seized by the Chinese only in 1662, decades after the Pilgrims arrived in Massachusetts.

But Tullock also notes — in an observation confirmed by modern genetic research — that "the southern Chinese and the northern Chinese are quite different. You can tell them apart. The southern Chinese are shorter. There’s a substantial Turkic element [from repeated barbarian invasions] in northern China."

Which could matter — at a time when the level of economic development in China’s southern coastal provinces is rapidly diverging from that of the interior.

Most American China-watchers don’t see a breakup on their radar screen. But Tullock is used to being in a minority.

"When I got to China [in 1948]," he says, "there were only two officials in the U.S. consulate who were not pro-Communist, myself and the commercial attaché. Everyone — not just State Department officials, but missionaries, businessmen — was so antagonistic to the Nationalists that they more or less thought anyone would be better." This expatriate antagonism, he believes, stemmed from a fundamental naiveté about Asia’s different, sometimes distressing, moral code.

Tullock argues that the U.S. arms embargo imposed on the Nationalists to force them to "negotiate" after their great 1947 victory at Siping in Manchuria ("but the embargo was maintained even when it turned out that the Communists were the ones who wouldn’t negotiate") ultimately ensured the Communist victory. Oddly, much the same happened in Vietnam nearly three decades later.

"I was inclined to think we could have supported [Nationalist leader] Chiang Kai-shek. And what happened in China was so very bad that it’s hard to argue it wouldn’t have been better," Tullock says. He cites estimates that 35 million Chinese were exterminated in 1950-56 by the Communists after their victory. "And that’s not counting the only nationwide famine China has ever had [caused by Mao’s Great Leap Forward campaign], which the Chinese themselves say cost 15 million to 20 million lives. Because that was an accident."

Why did China stagnate? Tullock’s short answer: "The overwhelming civil service dominated the whole place." These "mandarins" — from the Portuguese word for "those who order" — can be traced back to early China, but were recruited by competitive examination in a remarkably modern fashion. The mandarin system was perfected and reached the peak of its power in the last imperial dynasties of Ming and Qing (1644-1911).

Characteristically differing with most sinologists, Tullock thinks the mandarins "were not all bad — like rule by college professors. Of course, they were no good at war, so they kept getting conquered by barbarians." But eventually, Tullock says, the mandarins became a classic rent-seeking elite.

"The perception that China was stagnant is a 19th- and early 20th-century point of view," Tullock points out. Previously, he says, China was seen to be the world’s most advanced civilization. Recent research shows a continuous history of technological development. True, the great expeditions of Admiral Zheng He to Arabia and Africa (in 1405-33) were deliberately never followed up. However Tullock argues that Norwegian restrictions on Icelandic shipbuilding, imposed to maintain political control, similarly prevented exploitation of the Viking discoveries in North America.

"But I question whether the mandarins would have allowed an industrial revolution," Tullock adds. "That’s the real question: not why did China stagnate, but why did Europe move ahead?" He speculates that lack of central control in Europe prevented rent-seeking elites from suppressing innovation. If it was repressed in one small European state, it simply sprang up in another.

If China regresses, it may have company. Tullock emphatically does not share the view that Western-style liberal, democratic capitalism has triumphed for good.

"If you went back to the Mediterranean basin in 200 B.C.," he says, "you'd have found it surrounded by city-states which depended on voting … the Roman republic, Carthage, the Greek city-states. Two hundred years later, they were all gone. Rome had become an empire, and they'd all been absorbed. And if you'd gone back to Europe in 1400, you'd have found free cities that were self-governing, and more or less democratic, and the various monarchies had parliaments … . England was not by any means the only one. By the 18th century they were almost all absolute monarchies."

We've become accustomed to thinking that the past decade has witnessed the final triumph of democratic capitalism — the "end of history." Tullock is not so sure. With one eye perhaps on Washington, D.C.’s increasing tendency to regulate our lives and personal behavior, the scholar suggests a rent-seeking mandarinate could triumph. It could even happen here.

Peter Brimelow is editor of VDARE.com and author of the much-denounced Alien Nation: Common Sense About America’s Immigration Disaster, (Random House — 1995) and The Worm in the Apple (HarperCollins — 2003)