04/22/1995

April 22, 1995

Scripps Howard News Service

A dramatic preview of the first decades of the 21st century was published in the Atlantic Monthly in February 1994. Robert Kaplan used the current dissolution of West Africa to illustrate the coming anarchy as borders crumble and nations break up under the tidal flow of refugees from ethnic conflicts and environmental disaster.

Kaplan believes that the future’s winners will be countries that have maintained cultural identity. This leaves the United States out. Kaplan writes that ''it is not clear that the United States will survive the next century in exactly its present form. Because America is a multi-ethnic society, the nation-state has always been more fragile here than it is in more homogeneous societies like Germany and Japan.''

The United States, he believes, has been transformed from a country into a collection of cultures.

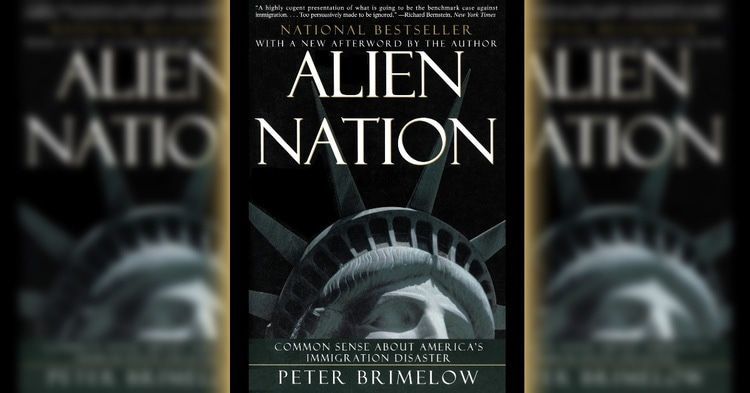

Kaplan will be even more pessimistic once he reads Peter Brimelow’s new book, Alien Nation, published this month at Random House. Brimelow shows that Camelot liberals used the 1965 Immigration Act to abolish the ''national origin'' basis for immigration and to destroy the melting pot.

Prior to 1965 immigrants to our shores had cultural ties. Moreover, there were lulls in the flow of immigrants which permitted time for them to become assimilated. Today, however, 83% of legal immigrants and practically all of the illegal immigrants are ''protected minorities'' and there are no lulls in the massive inflow of diversity.

The flood of immigrants, together with their higher reproductive rates, is changing the racial character of the U.S. population. Sometime after the middle of the 21st century, whites will become a racial minority.

Brimelow shows that the United States is already on the road to break-up. Four separate regions are emerging: an Asian Pacific coast, a Hispanic southwest, a black and white southeast and northeast and a white landlocked center.

Why is the United States using its immigration policy to import the ethnic strife and social failure that breeds anarchy? For what reasons has the United States elected to become ''a colony of the world?''

There is no answer to these questions. Some economists have attempted to argue that immigration is necessary to stimulate economic growth and to fill unattractive jobs that the native-born won’t take. Brimelow examines the economic case for immigration and finds it to be totally without merit.

Some immigrants are highly skilled, but there has been a sharp relative deterioration in immigrant skills in recent years. Consequently, they are earning less than the native-born and contributing to a widening income inequality that politicians use to justify more welfare spending.

The increased job competition from immigration has taken a toll on American blacks, too, whose unemployment rate has risen with the post-1965 opening of the immigration floodgates. Politicians have responded by expanding racial preferments, thus further undermining social cohesiveness.

Brimelow has made a sound case that U.S. immigration policy quickly needs a radical overhaul. If not, the racial polarity and social fragmentation that Robert Kaplan catalogued over a year ago will accelerate. A collection of diverse cultures is not a people, and without a people there is no country.