By Steve Sailer

12/09/2009

We all know that an immediate immigration moratorium is essential for the survival of the American Republic and, rather less importantly, for America’s Republican Party.

But while we're waiting for the moratorium, there’s a lot of stuff that can be done.

The genius of the Founding Fathers was that they recognized America contained differing communities that needed a federal rather than a unitary political system. Now, arguably, the established states themselves contain differing communities that should be given expression.

Typically, U.S. political boundaries have been drawn by partisans, resulting in the notoriously absurd shapes of many U.S. Congressional districts. The U.S. gave the waiting world the term "gerrymandering" after a constituency resembling a salamander drawn up by Massachusetts governor Elbridge Gerry.

In a similar spirit, what I’m proposing here is what Peter Brimelow insists I call a "Sailermander" — it’s aimed at preserving, not a political party, but the hegemony of the historic American nation, otherwise likely to be swamped by legal and illegal immigration.

My first proposed Sailermander: Texas.

The 1845 treaty of annexation gave the new state of Texas the right to split into five states at least arguably.

With modern Texas providing relatively effective government without high taxes or high land prices, the state has attracted a population (now approaching 25 million) huge enough to justify being divided up into five smaller states.

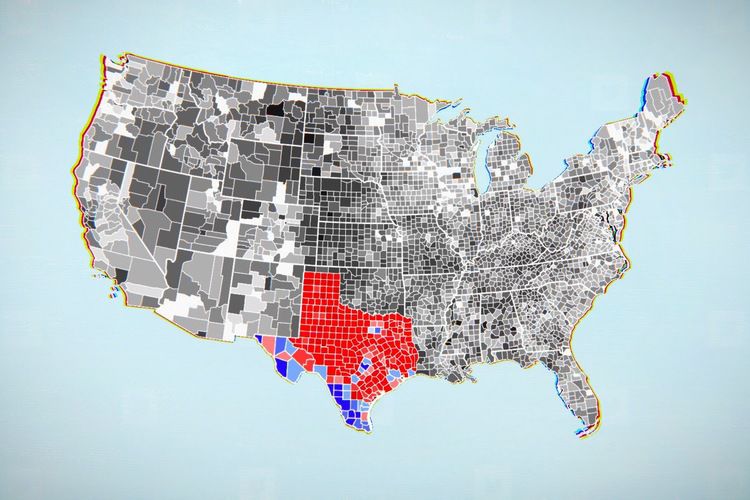

Here’s Nate Silver of FiveThirtyEight.com’s fanciful map of what a split-up Texas might look like politically, using Texas’s 254 counties as building blocks.

(Silver’s state names are all wrong, of course. Texans would never agree to any names for new states that didn’t include the word "Texas" in them — such as South Texas, West Texas, North Texas, East Texas, and Central Texas.)

Divvying up Texas may seem at present irrelevant — none are prouder than Texans of the humongousness of their state. But thinking through the implications of this scenario is illuminating.

Splitting Texas is the kind of change that would be more conceivable to Canadians than Americans. Although Americans like to think of Canada as boring, America’s political institutions have been much stodgier at the macro-level than Canada’s. Canada’s national borders have been enlarged as recently as 1949 (when Newfoundland, formerly a dominion ruled from London, not Ottawa, joined). The French-speaking province of Quebec came within 53,000 votes of seceding in 1995.

Moreover, Canadian parties are far more volatile than the American duopoly. In 1993, for example, Canada’s ruling Progressive Conservative entered the general election holding a majority of seats and exited with just two. The Progressive Conservatives subsequently went out of business, a fate that hasn’t befallen a major party in U.S. since the Whigs. (Even being on the losing side in the Civil War didn’t do the Democrats any long-term damage).

But, basically as a result of the unprecedented post-1965 mass immigration, it’s probable that Americans will eventually find ourselves living through what the Chinese would refer to as politically interesting times. It’s worth starting to think about long-range changes in the institutional landscape so that they won’t catch us unawares.

No states have been added to the Union in a half century. But the issue dominated American politics in the 40 years preceding the Civil War. And it’s likely to emerge again.

The Democrats have solid reasons to promote Washington D.C. and/or Puerto Rico to statehood whenever it looks like they can get away with it. Each would provide them with two additional Democrats in the U.S. Senate, along with five or six Democratic members of the House of Representatives for Puerto Rico and one for Washington D.C., with corresponding advantages for the Democrats in the Electoral College.

Of course, the last time Puerto Rican statehood came up for a vote in the House, it was pushed through to a 209-208 victory by a Republican, Speaker Newt Gingrich, motivated by the delusion that Puerto Rican statehood would somehow attract Mexican voters to the GOP!

Few events demonstrate the cluelessness of the Republican elites about the political implications of demographic change than this bizarre incident. Wiser Republican heads allowed Gingrich’s Folly to die quietly in the Senate.

Of course, the more intelligent GOP plan for Puerto Rico would be to prepare the Spanish-speaking island nation for independence — after more than a century of colonial rule since we acquired it from the Spanish in 1898.

Newt’s misadventure illustrates why statehood for Puerto Rico and Washington D.C. is likely to come up again. It’s kind of like gay marriage — which, after losing 31 straight times when put to the electorate, has been renamed "marriage equality". What, are you against equality? Likewise, statehood for D.C. and P.R. will at some point be turned into racial equality issues — which are hard to withstand under our age’s reigning mindset.

You're against electoral equality? What kind of racist are you?

Threatening to split Texas into five states would be an effective Republican counter-gambit.

States have split before. Famously, West Virginia was carved out of Virginia during the Civil War. But a more relevant example might be Massachusetts splitting itself as part of the Missouri Compromise of 1820. Its northern section became the free state of Maine to balance off the admission of Missouri as a slave state.

Depending upon how adroitly the state borders are gerrymandered, splitting Texas could create a net gain for Republicans in the Senate of two or four Senators. Texas currently sends two Republicans to the Senate. Five Texases would likely send seven or eight Republicans to the Senate, for a net increase of two or four — assuming most of the Democrats are corralled into a new Hispanic-dominated state of South Texas along the Rio Grande. Creating a heavily Hispanic state in south Texas would almost certainly add two Latinos to the Senate — how could anybody be against that? Republicans would be delighted to demonize Democrats who opposed splitting Texas as racists who don’t want Hispanics to have their own state.

Splitting Texas is also worth thinking about because of the long-term impact of mass immigration, the GOP’s Self-Destruct Mechanism, on the Electoral College.

Almost all states cast their Electoral College votes in a winner-take-all fashion. That means a handful of big states play a crucial role in determining the viability of a party in Presidential elections. The GOP, for example, did well in Presidential elections from 1952 through 1988 in sizable part because it carried California nine out of ten times.

Since then, however, immigration-driven demographic changes, and the pusillanimous reaction of the California Republicans, have converted California into the Electoral College keystone of the Democrats. That leaves the GOP reliant upon Texas, with its 34 electoral votes — probably increasing to 37 or 38 after the 2010 Census.

Republicans have done very well in Texas recently, in part due to Texans named Bush being on six of the last eight national tickets. In 2004, George W. Bush cruised to victory with 61 percent in Texas. In 2008, however, John McCain fell to 55.5 percent.

That was still a comfortable margin. Yet, it raised the first hints of the GOP’s Specter of Electoral College Doom: due to the increasing Hispanic population in Texas (today, 30 percent of all residents of Texas speak Spanish at home), Texas will someday flip Democratic, leaving any Republican Presidential candidate in a huge hole to climb out of in the Electoral College.

Texas’s Hispanics are a little more Republican than the national average: 35 percent voted for McCain versus 31 percent of Latinos across the country. Yet the gap between Latinos and whites was larger in Texas (38 points) than in any other state in 2008, because McCain carried 73 percent of Texas' white vote.

Splitting Texas would add eight more votes to the Electoral College due to the creation of eight more Senators. However, it probably wouldn’t increase the GOP’s performance in the Electoral College, and might even hurt it. Currently, the GOP consistently wins all 34 of Texas’s Electoral Votes. If split into five states, the Electoral Votes of at least one (and possibly two) of the five Texases would go to the Democrats.

Nevertheless, from the point of view of Republican performance in the Electoral College, splitting Texas makes sense as a salvage operation when the entire state is ready to flip Democratic in Presidential elections. And that’s not far off.

Here is table of what Nate Silver’s five states of Texas would look like:

|

Silver’s Name |

Sailer’s Name |

Capital |

Electoral Votes |

Population |

McCain’s Share |

% White |

|

El Norte |

South Texas |

El Paso |

6 |

2,527,314 |

34% |

13% |

|

Plainland |

West Texas |

Lubbock |

6 |

2,500,681 |

74% |

66% |

|

Trinity |

North Texas |

Dallas |

13 |

7,549,968 |

58% |

58% |

|

Gulfland |

East Texas |

Houston |

11 |

7,494,089 |

56% |

47% |

|

New Texas |

Central Texas |

Austin |

8 |

4,254,922 |

50% |

50% |

|

44 |

Silver, a baseball statistician who started his political analysis career at the liberal Daily Kos, has gerrymandered his break-up of Texas to make it less bad than it could be for Democrats. Silver lumps most of the population into two large states in the East. His hope is that the Democrats would win two of two Senate seats in South Texas, one of two in Central Texas, and one of four in North and East Texas, making them no worse off than at present.

A fairer division into more equal sized states, however, could easily be gerrymandered by the Republican legislature into something more promising for the GOP. Their goal would be to group as many Democrats as possible into one state, just as Republicans have used the Voting Rights Act for years as justification to create super-liberal majority-minority Congressional districts in order to maximize both the number of minority House members and the number of mildly Republican-leaning districts.

On the other hand, Silver’s map does show the limits of this kind of gerrymandering on a scale larger than a House district.

There’s a fundamental problem with trying to redraw political boundaries to group most of the minority Democrats together: minority Democrats can’t afford to live only around other minority Democrats, because minority Democrats don’t create many jobs. Thus, minority Democrats tend to live in the middle of white Republican regions. This makes it hard to gerrymander Texas Democrats into one contiguous state with a shape that isn’t overtly contrived.

For example, the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex might deserve to be called the heart of the Republican electorate in the U.S. Yet, within the Metroplex, Dallas County, the blue dot in the upper right of the map (and ninth largest county in the country with 2.4 million people), gave only 42 percent of its votes to McCain.

If you follow a rule that new states have to be constructed out of existing counties and must be contiguous (i.e., no separate free-floating pieces), then it’s very difficult to link Dallas’s slums with any other concentrations of Democrats. There are just too many Republican Hank Hill-types between inner city Dallas and the STWPLs of downtown Austin to make it worthwhile.

The highly Hispanic left bank of the Rio Grande might seem like an exception to this rule. But notice that this vast expanse of riparian land from El Paso to Brownsville on the Gulf of Mexico is home to only ten percent of Texas’s population. Mexican immigrants try to not tarry in South Texas, because it’s so poor. The Lower Rio Grande Valley in Texas is rather like the Upper Rio Grande Valley in New Mexico, a state that has had a sizable Hispanic population since 1609, but which doesn’t attract many immigrants because of its lack of economic dynamism and its political corruption.

You have to look at it from a Mexican’s point of view: Why go to all the trouble of illegally immigrating to New Mexico to live near a whole bunch of poor Hispanics when you could just stay home in Old Mexico?

No, the reason illegal immigrants swim the Rio Grande is to live within commuting distance of job-creating white Americans. This means that Hispanic populations tend to be dispersed into numerous urban areas across the southern two-thirds of America. In turn, redrawing large-scale political borders (such as state boundaries) is not a really effective way for the GOP to deal with its onrushing demographic problem, because prosperous Republican white people are magnets for illegal immigrants.

Of course, once too many illegal immigrants' children show up in an urban school district, the white people tend to up and move. But a lot of minority parents don’t want to send their kids to those schools, either, so they try to follow the whites to the 'burbs, which then turn into slums, too. Much of the Housing Bubble / Crash that set off the Great Recession, for example, was a result of minorities fleeing California’s old barrios for new inland exurbs, whose home prices deflated once they turned into new barrios.

There’s no stable resting point in this system. It leads to a constant churning of the population across the landscape. (Needless to say, real estate developers, real estate agents, and mortgage brokers consider that a feature, not a bug.) Thus, internal political boundaries that are redrawn to make ethnic and partisan sense today generally won’t make sense in another generation.

Changing political borders within America is a reasonable and sometimes useful part of the toolkit. It may prove to be very necessary.

But in the end, the place to make a stand is on the American border itself.