Schooled in Adversity

05/05/2000

Times of London, February 17, 1990

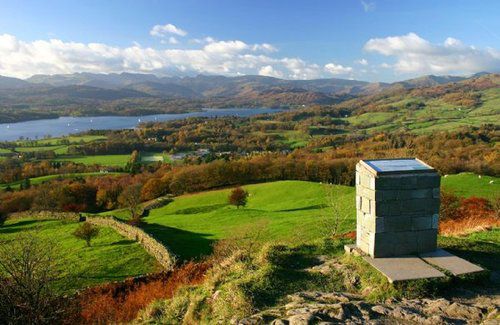

Peter Brimelow writes: Tom Brokaw hadn’t instructed us that they were the "Great Generation" when I published this column on the death of my father for a British audience (London Times, February 17, 1990). Almost exactly ten years later, we scattered his ashes along with my mother’s on Orrest Head, above Windermere. "The finest view in the Lake District, and, perhaps, the finest in Great Britain," according to the quaint old guidebook they took there on their honeymoon. We could see nothing through the driving rain and mist.

When my mother was a little girl, a school trip culminated on the top of Orrest Head and all the pupils sang in unison "Land of Hope and Glory." [Listen(MP3)] It is an interesting question what song, in such circumstances, her American grandson might be required to sing.

The British are Europe’s great emigrant race. Today, about six million Britons live abroad. In some corner of their minds, many of them are constantly in fear of what my brother and I have just been through: a telephone call bringing news of the death of a parent thousands of miles away.

After the scramble to the airport, the long flight gives you a lot of time to brood on the youthful whim that sent you so blithely into exile. As it happened, my father, Frank, seemed positively intrigued by his sons' wanderings. He too loved to travel, and had just finished packing for Florida, where we planned to celebrate his 75th birthday, when the fatal hemorrhage struck without warning.

Perhaps I am traumatized by the social chaos of New York, but I found the smooth functioning of some much-maligned British institutions deeply impressive. An ambulance had arrived within seven minutes. The emergency medical staff had been swift (in vain, alas) and kind. My mother’s doctor was automatically notified. He called to see her without being asked. At this point, any transatlantic sensibility is twanging instinctively at the prospect of massive bills, but the National Health Service, whatever its problems, still provides.

Similarly, the Church of England fulfilled its function as an established church by gracefully conducting the funeral without any of the quibbles about regular attendance that disfigure many such occasions here. In last weekend’s Sunday Times, Frank Field MP reported an increasing tendency for these objections to be raised in Britain. He even cited the case of a vicar in Birkenhead refusing to baptize the child of non-churchgoers. Birkenhead was my parents' home, but St. Saviour’s Church did not hesitate.

This has been the best and worst of centuries, depending to a chilling extent on when you were born. For the baby-boom generation that followed the Second World War, in Britain at least it has been a time of placidity, prosperity and, most recently, the tantalizing prospect of an international golden age. But my father’s generation was squarely in the path of a succession of history’s most terrible waves.

He was born during the First World War, when his own father was on the Western Front. One of his earliest memories was of being shown a photograph of his father in uniform and carrying a swagger stick, with which, he was told, he would be beaten for some childhood misdemeanor when his father returned. This, he said, naturally made him quite dubious when his father did return in 1918.

He left school in a northern town devoured by the Depression. After months of unemployment, a job came up in the town’s passenger transport department. Years later, when he was successfully managing scores of buses and hundreds of employees in another northern city, I was shocked to hear him say serenely in response to my question that he wasn’t particularly interested in his life’s work at all, and would have much preferred to be a lawyer. But family circumstances had made that impossible. So he uncomplainingly "got on with it". To him, getting on with things was the supreme virtue.

He spent the Second World War in the Army. Four years in the Western desert left him with a deep respect for the German army and also for the Jewish settlers in Palestine. Both groups notably got on with things.

In the summer of 1967, he surprised us by surfacing to make the first comment I recalled him making on public affairs since Suez: the Israelis, he said, were about to get on with destroying the Egyptian army. And they would succeed triumphantly, despite the Egyptians' superiority in arms and equipment that was then preoccupying the commentators.

The generation that was born in the Great World War was buffeted by less obvious turbulence. My father was quietly but intensely patriotic, although he lived in a period of humiliating national decline. He managed labor-intensive local government enterprises in a time of politicized labor unrest which valued the quality of getting on with things less and less. In his retirement, he saw Mrs. Thatcher’s privatizing reform eliminate this battleground just as completely — although perhaps with more purpose — as Britain’s strategic collapse had nullified his Eighth Army years.

Even the generation gap worked against his age group. He used to say wryly that its members had been oppressed by their parents, the last Victorians, and then by their children, the product of the 1960’s.

My father never complained, which was typical of his gentle generation. When they left school, the dole queues were waiting for them, but they did not react with mugging and burglary. When the Second World War broke out, they served. In all of their country’s crises, they responded calmly but reliably — arguably too calmly, but this was the characteristic that made them the backbone of England.

In the passage from Luke that my brother chose for the funeral service, the centurion has the faith to ask Jesus not to come personally to heal his servant, but to do so with a mere word. "For I also am a man set under authority, having under me soldiers, and I say unto one, Go, and he goeth; and to another, cometh; and to my servant, Do this, and he doeth it."

It is an epitaph not just for my father but for an England that is, without fuss, slipping away.