Steve Jobs: Nature, Nurture, And Apricot Orchards In Silicon Valley

By Steve Sailer

11/08/2011

Slugger Yogi Berra liked to say, "You can observe a lot by watching." And you can observe a lot about what modern Americans actually value just by watching their heroes.

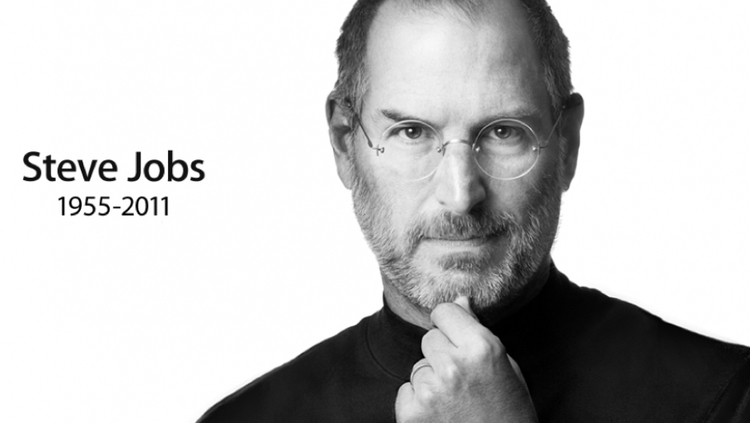

Nobody in recent memory earned more lavish obituaries than Steve Jobs, cofounder of Apple Inc. He was immediately beatified as a secular saint following his death on October 5th of cancer at age 56.

A middle-class white Baby Boomer, a child of the Sixties, Jobs vastly appealed to the middle-class white Baby Boomers who still dominate culturally.

Yes, I realize we Baby Boomers are insufferable. But you are going to miss us when we are gone. The “diverse” America of the future is going to be a lot less interesting.

For example, in an upcoming CNN documentary Black in America, scheduled to air November 13, Soledad O'Brien exposes the scandal that few blacks have been allowed to found their own successful high tech firms.

Blogger Michael Arrington has gotten himself in lots of trouble for admitting in an interview with O'Brien that he doesn’t think this is caused by discrimination. Vivek Wadwha and Anil Dash piled on Arrington. (Of course, nobody mentioned the similar lack of Mexican-Americans in Silicon Valley.)

Ironically, in his new authorized but frank and judicious biography, Steve Jobs, Walter Isaacson lets slip this about the seven executives of the hugely successful new management team that Jobs built at Apple in the last decade:

"Even though there was a surface sameness to his top team — all were middle-aged white males — there was a range of styles."

Of course, it’s hardly a surprise, at least to VDARE.com readers, that Apple under Jobs didn’t employ many blacks or Hispanics in high-level positions. What’s more intriguing is that East Asian or South Asian names are also rare throughout the 630 pages of Steve Jobs.

Jobs’s accomplishment of taking his firm from a garage to the peak of financial success is astonishing. Apple now vies with ExxonMobil (founded by John D. Rockefeller in 1870, more than a century earlier) for the highest stock market valuation in the world. That Jobs was exiled from Apple from 1985 to 1997, only to return in his forties and take it to the top, makes his story even more amazing.

Of course, Jobs died at exactly the right time for the sake of his legend. If he'd lived another decade, Apple either would have declined or would have achieved his goal of world domination of digital information, turning Jobs into the Big Brother figure from Ridley Scott’s famous 1984 commercial introducing the Macintosh.

But the publication last month of Isaacson’s biography has slightly deflated the hoopla. While Isaacson admires much about Jobs, he also discovered that his subject was a jerk.

And that’s putting it mildly — Jobs’s employees constantly refer to their mercurial and foul-mouthed boss using a seven-letter word.

For example, Jobs’s tremendous chief of design, Jonathan Ive, points out to Isaacson that Jobs isn’t some autistic prodigy accidentally stepping on other people’s feelings:

"He’s a very, very sensitive guy. That’s one of the things that makes his antisocial behavior, his rudeness, so unconscionable. … Because of how very sensitive he is, he knows exactly how to efficiently and effectively hurt someone. And he does do that."

Capitalism is a wonderful outlet for intense, charismatic personalities, such as Jobs. Making shiny cool stuff is much better for all concerned than, say, invading Russia.

It’s a problem that Isaacson had to ditch his biography’s original title, the self-mocking iSteve: The Book of Jobs. That goofy name would have alerted readers to the essentially comic nature of the narrative. But I’ve used "iSteve" as my web domain name since the 1990s ("Like I, Claudius or I, Robot, only even more pompous!") and I publicly objected to Isaacson and Jobs infringing upon my intellectual property. (I've registered the trademark iSteve.) Isaacson then changed the book’s title to the boring Steve Jobs.

I suspect, though, that many readers won’t get the joke, and will merely be appalled by Jobs’s nastiness.

Two days after Jobs’s death, Sony Pictures, which has had middling-sized hits with the business films The Social Network and Moneyball, paid a million dollars for the rights to Steve Jobs. Hopefully, the fact that the actor who looks the most like the young Jobs is the goofball sit-com star Ashton Kutcher will impel the studio to craft this biopic more as a comedy than as a tragedy.

Of course, Jobs’s temper tantrums served a purpose. Although repeatedly lauded as the "inventor" of Apple’s many outstanding products, Isaacson’s interviews show scant evidence of Jobs inventing much. Here’s one of the countless screaming arguments Isaacson relates, this one over advertising for the iPad:

"When [Ad man James] Vincent shouted, ‘You've got to tell me what you want,’ Jobs shot back, ‘You've got to show me some stuff, and I'll know it when I see it.’"

Instead of a James Watt, Jobs was more like a great art patron, such as Pope Julius II. (The Apple CEO would have made a fine Renaissance cardinal.) While he didn’t come up with much himself, he possessed superb critical taste and a sadistic talent for motivating more creative underlings to do better.

One pattern that recurs in photos is the hawk-like Jobs — a fruitarian, Jobs was always on the verge of anorexia — paired with a plump, pleasant nerd such as Steve Wozniak (the human hobbit who more or less invented the personal computer in 1975 and then wanted to give his plans away to his fellow hobbyists until Jobs convinced him they should make money off them), Andy Hertzfeld (developer of much of the Macintosh code), and John Lasseter (director of Toy Story for Pixar, which Jobs had bought from George Lucas).

Jobs’s basic management technique is one known to dog trainers for creating the most emotionally dependent pets: erratic reinforcement. Seldom able to solve problems himself, Jobs responded to his underlings' proposed solutions with extreme emotional violence: either the employee was a genius or an idiot. This method elicited extraordinary efforts as Jobs burned through the primes of numerous nerds.

Of course, this seemingly random vehemence won’t work for long unless you are right more often than random chance predicts. And Jobs was, on average, more right than wrong about what the public was going to want — once Apple showed it to them.

One of the keys to Jobs’s success was that, by Silicon Valley standards, he wasn’t much of a nerd himself, and refused to let himself be intimidated by nerds' mastery of technical trivia. Even when young, he possessed a busy middle-aged man’s impatience with the Aspergery personalities that congregate in Silicon Valley.

Jobs made computers for people who don’t like computers. On the other hand, despite his Sixties affectations, he certainly didn’t make computers for the masses, either. He made high quality products for customers whose time was more valuable than average and could afford Apple’s staggering mark-ups. And this exemplifies the legacy of the Sixties, which turned out to be beneficial to the upper reaches of society, while largely ignoring the impact on the lower orders.

How do you get to be the top businessman in America?

The first element is will, which Jobs had in abundance.

The second is luck. For example, getting to know the older brother of a high school classmate, who turned out to be the hardware genius Steve Wozniak. Jobs was lucky to have been raised in Santa Clara County, the R&D capital of the military-industrial complex, where every other dad on the block was an engineer. That the San Francisco Bay area was also the center of hippiedom interacted in unforeseeable ways with the slide rule set.

The third and fourth factors are nature and nurture. One fascinating aspect of Steve Jobs is that Isaacson provides enough detail to allow the reader assess the impact of Jobs’s being adopted. He was a one-man adoption case study, whose life embodied much of what social scientists have learned about the impact of nature and nurture.

Adoption was not uncommon during the middle of the 20th Century. But after the legalization of abortion in the 1970s, the supply of middle class white babies started to dry up. Sentiment turned against adoption as people (at least those who had already been born) seized upon the notion that adoptees would inevitably grow up damaged, thus making abortion seem more humane than adoption. (Isaacson has caused a bit of a scandal by quoting Jobs saying, "I’m glad I didn’t end up as an abortion.") Since there’s never a shortage of unhappy individuals, there was an ample supply during the 1980s and 1990s of stories in the press about unhappy adoptees. Normally, there’s no market for happy tales about adoptees.

So it’s refreshing that Jobs, who was so critical of everyone else, was hugely satisfied with his adoptive parents and the pleasant suburban life they provided for him, despite their being high school dropouts.

Indeed, Job’s outspoken loyalty to his adoptive parents is the single most likable thing about him. Jobs was a stingy man, who seemingly went out of his way to not spend money on people close to him. For example, he would pick out dresses ideal for his 1980s girlfriend, singer Joan Baez, who was a celebrity but not particularly rich. But then he'd expect her to pay for the dress herself while he went off and bought himself some shirts. (In case you are wondering, unlike Bill Gates, Jobs seldom gave any money to charity.) His one large gift, however, was the $750,000 he gave his parents when Apple went public in 1980. They paid off their mortgage and started taking an annual cruise, but stayed in the same house, content.

Because prospective parents were carefully vetted by adoption agencies, they tended to be fairly average in positive qualities, such as income, education, and intelligence, but less likely to have major flaws, such as alcoholism or criminal tendencies. Jobs’s adoptive parents exemplified this tendency. Despite their modest intellects, back in that era of decent wages for blue collar workers and cheap houses they were able to provide him with a stable, happy home in Mountain View, California.

But, Isaacson writes:

"Then a more disconcerting discovery began to dawn on him: He was smarter than his parents. …

Researchers into the effects of adoption have found that heredity plays a large role in adult IQ. Conversely, they've had a hard time proving that upbringing has any effect. That’s probably partly because of a "restriction of range" problem with adoption studies. Adoption agencies try to weed out unpromising applicants. Parents of good character, such as the Jobses, can put their adopted child on the right path even if they can’t intellectually accompany him all the way. Isaacson continues:

“Not only did he discover that he was brighter than his parents, but he discovered that they knew this. Paul and Clara Jobs were loving parents, and they were willing to adapt their lives to suit a son who was very smart — and also willful."

IQ scholars have found that individuals tend to create their own environments that suit their genes. Thus, when the bright lad was promoted from fifth grade to seventh grade, he found his new junior high school full of juvenile delinquent bullies and demanded that his parents transfer him to a better school. According to Jobs, they "scraped together every dime and brought a house for $21,000 in a nicer district" — Cupertino-Sunnyvale.

A homeboy, Jobs has seldom had to cope with homesickness. Apple’s headquarters are in Cupertino. And one of the last projects he took on before his death was getting approval from the Cupertino city council for a new 150-acre headquarters campus that will combine a spaceship-like circular building with the pastoral past. Isaacson reports:

"One of his lingering memories was of the orchards that had once dominated the area, so he hired a senior arborist from Stanford … 'I asked him to make sure to include a new set of apricot orchards,' Jobs recalled.’You used to see them everywhere, even on the corners, and they're part of the legacy of this valley.'"

The Jobses went on to adopt a sister for Steve, but "my adopted sister … and I were never close." This is in line with the findings of twin and adoption studies: almost no correlation in IQ between adoptive siblings raised in the same house.

Of course, being the sister of a master manipulator like Steve Jobs couldn’t have been easy. You would be guaranteed to wind up the loser in the inevitable sibling rivalry.

Being Steve Jobs, he had to feel hostile toward somebody, so he lashed out at his biological parents for having "abandoned" him. Sometimes Jobs would attribute his habitual horridness toward those close to him to his having been given up for adoption. But that seems like a stretch.

His biological parents, unsurprisingly, were grad students. His genetic mother was a German-American girl, while his father (shades of Barack Obama Sr.) was something of an exotic, the son of one of the wealthiest families in Syria, who came to America and earned his Ph.D. in a social science.

Ethnically, his biological parents were quite similar to his adoptive parents (the Jobses were German-American and Armenian-American). That meant he resembled his adoptive parents, which makes things easier.

Her Catholic father objected to a Muslim son-in-law, so she gave the baby up for adoption. But after her father died, the couple married and had one daughter, who grew up to be award-winning novelist Mona Simpson. The biological brother and sister didn’t meet until they were in their mid-20s, but then got along famously. Simpson delivered an eloquent eulogy for her brother at his funeral.

Simpson’s 1996 novel, A Regular Guy, is about Jobs’s on-and-off relationship with his own illegitimate daughter Lisa, for whom he named Apple’s failed 1983 computer but otherwise didn’t do much else for years. When the novel was published, Lisa, a Harvard student (she once had to borrow her tuition from Hertzfeld, the Mac programmer, because her father was being moody) vociferously objected to her new aunt violating her privacy. Novelists tend to be vampires for material.

Like Obama Sr., the biological father had split after a few years. A restless sort, he stopped being a professor and started managing restaurants. Simpson discovered, incredibly, that her father and her brother had unwittingly met a few times when the bio-dad managed a restaurant in San Jose. He remembered Jobs as "a big tipper." He recently married for the fourth time and is still working, in his 80s, as a manager at a Nevada casino. His son, worried that he'd be hit up for money, never reached out to him.

In retrospect, it seems that Jobs got the best of both worlds, benefiting from the nature of his gifted but flakey biological parents and the nurture of his limited but admirable adoptive parents.

Politically, Jobs was the kind of person who identifies as a Democrat due to generational loyalty (in the good old days, he had dropped a lot of acid while listening to Dylan LPs). On immigration, he held the standard self-interested views of high tech tycoons who, despite their vast wealth, want salaries for their engineers pounded even farther down.

Interestingly, however, Jobs showed no interest in helping illegal immigrants. Isaacson reports on a 2011 dinner meeting with President Obama:

"When Jobs’s turn came, he stressed the need for more trained engineers and suggested that any foreign students who earned an engineering degree in the United States should be given a visa to stay in the country."

Silicon Valley’s genius billionaires never seem to notice the self-fulfilling prophecy aspects of their calls for ever cheaper labor. Jobs’s own (adoptive) parents managed to own a house with a garage (the garage where Apple was founded) in Los Altos even though his high school dropout father was a machinist and his mother a bookkeeper, Today, of course, they'd have to live in the sweltering Central Valley and endure four hour roundtrips to their jobs in Silicon Valley.

So, from the point of view of American students, why bother? If you aren’t a Mark Zuckerberg-like potential superstar, what is the point of investing in a degree in at computer programming or engineering when your bosses are constantly lobbying the President of the United States to erode your salary by letting in more skilled immigrants to compete with you?

Even more informative, however, is Obama’s response and Jobs’s reaction:

"Obama said that could be done only in the context of the 'Dream Act,' which would allow illegal aliens who arrived as minors and finished high school to become legal residents — something Republicans had blocked."

Obama keeps his eyes on the prize of Democratic hegemony through turning illegal aliens into voters. Jobs, though, showed zero interest in the so-called plight of the undocumented;

"Jobs found this an annoying example of how politics can lead to paralysis. 'The president is very smart, but he kept explaining to us reasons why things can’t get done,' he recalled. 'It infuriates me.'"Jobs went on to urge that a way be found to train more American engineers. Apple had 700,000 factory workers employed in China, he said, and that was because it needed 30,000 engineers on-site to support those workers. 'You can’t find that many in America to hire,' he said. The factory engineers did not have to be PhDs or geniuses; they simply needed to have basic engineering skills for manufacturing. Tech schools, community colleges, or trade schools could train them. "If you could educate these engineers,' he said, 'we could move more manufacturing plants here.'"

Okay, how could Silicon Valley motivate more Americans to get the training to be engineers?

Hey, I've got a crazy idea! They could offer to pay Americans more!

I know the idea of Apple, which has $26 billion in cash and short term investments on its solid gold balance sheet, offering more to its lowlier workers sounds nuts, but it’s so wacky it just might work.

Or, at least, Apple could stop lobbying the federal government to drive down the pay of Apple workers through increased immigration.

It might save a few of those apricot orchards too.