03/17/2001

Truth Follows Fiction: Camp Of The Saints begins in France, by Paul Craig Roberts

One of the useful, (but not pleasant) things about having a sense of history is that you are rarely surprised by the awfulness of current events. Everything has happened before.

This is certainly true of the "Camp of the Saints" phenomenon. Everyone has heard of the Irish Potato Famine of the 1840’s, when thousands fled Ireland to avoid starvation.

There was blame enough to go around. Irish coroners' juries sitting on deaths by starvation would give verdicts of "Willful murder by Lord John Russell", who was responsible for tariff laws that caused food to be exported, whereas non-Irishmen thought that basing your whole economy on a potato might be considered careless.

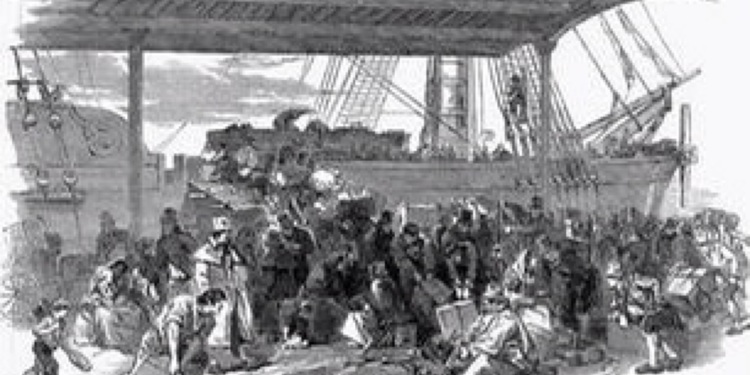

But in Canada’s eastern province of New Brunswick, they would get boatloads of a thousand people, with no food, little clothing, and no prospects of better.

So destitute were the people on their arrival [at St. John, N. B.] that the legislature voted £1500 sterling to alleviate the distress and a further sum of £1500 was collected in St. John. The victims of the famine were crowded into emigrant ships while in a low state of health and suffered from typhus on the voyage…In the month of June 35 vessels arrived with 5800 passengers and during the summer about 15,00 Irish immigrants were landed at Partridge Island. The total mortality was upward of 200 persons. Their bodies lie in nameless graves and their story is indeed a sad one.

The Faraway Hills Are Green, by Sheelagh Conway, Page 87

This was when the continent hadn’t been settled, of course. New Brunswick was largely miles and miles of trees. They had plenty of room. But I don’t know where they dug up the £3000.

In 1847, at the height of the famine, Irish Immigration peaked with some 74,000 arrivals at Quebec City alone. [Ten percent of these were Protestant, by the way.]

Overcrowded and filthy "fever ships" docked at the quarantine station set up on Grosse Île. On board lay hundreds of dead, destitute women men and children, many of them dying of cholera. During the summer of 1847, the recorded death rate hit forty or fifty a day. Often, corpses lay everywhere aboard ship. The living could not move, much less tend to the dead. Official statistics for Grosse Île show that between May 10 and July 24, 1847 some 4,572 people died on the voyage, on the ships at Grosse Île and in tents on the island. Another 1,458 people, including infants and children, died in the makeshift hospital on the island.

[Anti-British propaganda omitted for lack of enthusiasm.]

Quebec authorities were overwhelmed as hospital staff and clergy tried to cope. Landings and inspections came under military command, and soldiers policed the island to make sure the health stayed apart from the sick, and prevent the spread of disease.

Once they got clearance at Grosse Île., the Famine refugees moved on. Weakened and emaciated, many were already ill with cholera and typhus as they traveled on to Montreal, Kingston, Ottawa and the U.S. border at Detroit. In each of these cities, fever sheds had to be set up to accommodate the sick and dying.

The Canadian response varied from hostility to sacrifice.

(The Faraway Hills Are Green, p. 87-88)

One of the sacrifices was made by Toronto’s first Catholic Bishop, Bishop Power, who died as a result of his work in the fever sheds. There’s a monument to him in front of St. Paul’s Roman Catholic Church, on a street named after him in Toronto’s East End. There are now memorials on the sites of Grosse Île and other quarantine camps and talk of … wait for it … wait for it … reparations!

This is a horror story, and we would all like to prevent such things happening to people anywhere. But stop and think for a moment about what it was like for the people on the receiving end of this migration, what they gave, what it cost the people of North America who had to pick up after this tragedy.

Then stop and think what you want to pay to pick up after the human tragedies caused by the despotic governments of North Africa or Asia.

From the Canadian & World Encyclopedia:

The Great Famine of the late 1840s drove 1.5 to 2 million destitute Irish out of Ireland, and hundreds of thousands came to British North America. This wave was so dramatic that most Canadians erroneously think of 1847 as the time "when the Irish came. " The famine immigrants tended to remain in the towns and cities, and by 1871 the Irish were the largest ethnic group in every large town and city of Canada, with the exceptions of Montréal and Québec City.

The "Famine Irish," who supplied a mass of cheap labour that helped fuel the economic expansion of the 1850s and 1860s, were not well received. They were poor and the dominant society resented them for the urban and rural squalor in which they were forced to live.

[As for people being "forced" to live in urban and rural squalor, most squalor is self-inflicted. I know. My own apartment could be used as a model for P. J. O'Rourke’s Bachelor Home Companion.)

But the Famine Irish had another characteristic: the propensity to immigrate to the US. Thousands had left for the US by the 1860s, establishing a tradition that remained unbroken well into the 20th century. As a result, in Canada today "Irish" districts and communities are generally those that were established before the famine. For example, in the Maritimes, [East Coast] only Saint John [New Brunswick] has a significant Famine Irish element.

March 17, 2001