By Steve Sailer

03/08/2009

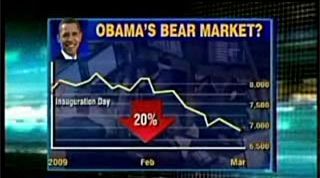

On the last day of the ill-fated Bush Administration, the Dow Jones average stood at 8,281, down catastrophically from its 2007 peak — yet still almost 25 percent higher than the Dow’s close on Friday, March 6, 2009 of 6,627.

You might think that George W. Bush would be an easy act to follow. After all, he was inept enough to overlook the basic rule of politics that kept the Bush family’s friends in Mexico’s PRI party in power for so many years: Make sure the economic collapse happens right after the election, not right before.

And yet, what is now technically the "Obama Bear Market" shows that Obama may be down to the challenge of being Bush’s successor.

It’s important to understand that Obama was never a Depression Democrat who worries that the capitalist system can’t produce enough wealth. Obama didn’t run for President to help Americans earn more money. By upbringing, he’s more a Sixties person who assumes that businesspeople will continue — in their unseemly way — to produce plenty of riches, which a better sort of person (such as, say, himself) should redistribute in a more equal and refined manner.

When Obama began his campaign in early 2007, this worldview made a certain amount of sense. In early 2009, however, it’s obviously out of date. We aren’t as rich as we thought we were before the bubble burst.

So far, Obama has implemented a three-pronged response to the Great Crash:

With Obama increasingly floundering, it’s time to revisit the questions that nobody seemed to have had the time to ask during Obama’s 20-month election campaign:

Who is he? What are his bedrock "emotional economics?"

Fortunately, the President published an informative 460-page memoir in 1995, Dreams from My Father: A Story of Race and Inheritance.

Unfortunately, few have paid much attention to what Obama has written about himself. The prose style is too elliptical and the story too boring to pay it careful attention.

That’s why I wrote my reader’s guide to the President’s autobiography, America’s Half-Blood Prince: Barack Obama’s "Story of Race and Inheritance." In this article adapted from my book, I'll explain what these dreams from his economist father were.

Barack Jr. barely knew Barack Sr., who had abandoned his wife and toddler son to obtain a Masters' degree in economics from Harvard before returning to Kenya to grab for the brass ring of power.

Instead, the son learned his father’s ideology from his still-smitten mother (with some assistance from her father Stanley, a failed salesman, but little from his skeptical maternal grandmother Madelyn, a bank executive). His mother’s indoctrination is the reason Obama grew up to write a book named after the father he barely knew.

It was in Indonesia, strangely enough, that his white mother began to painstakingly instill in little Barry Soetoro his biological father’s leftist politics of race.

This was his mother’s stratagem in her passive-aggressive war on Lolo, her unsatisfactory Asian second husband. Ann, a romantic leftist whose magnum opus was a 1,067-page anthropology Ph.D. dissertation with the Onionesque title of Peasant Blacksmithing in Indonesia: Surviving and Thriving against All Odds , despised Lolo for dutifully climbing the corporate ladder at an American oil company to support his wife and stepson:

"Sometimes I would overhear him and my mother arguing in their bedroom, usually about her refusal to attend his company dinner parties, where American businessmen from Texas and Louisiana would slap Lolo ’s back and boast about the palms they had greased to obtain the new offshore drilling rights, while their wives complained to my mother about the quality of Indonesian help. He would ask her how it would look for him to go alone, and remind her that these were her own people, and my mother’s voice would rise to almost a shout.

"'They are not my people!' "[p. 47]

Annoyed at seeing her talented son fall increasingly under Lolo’s kindly but irksomely pragmatic influence, Ann decided that the perfect role model for Barack Jr. in learning self-discipline would be Barack Sr.

"She had only one ally in all this, and that was the distant authority of my father. Increasingly, she would remind me of his story, how he had grown up poor, in a poor country, in a poor continent … He had led his life according to principles that demanded a different kind of toughness, principles that promised a higher form of power . I would follow his example, my mother decided. I had no choice. It was in the genes."

Over time, Ann’s strategy expanded to depicting the entire black race as the epitome of the virtues of self-discipline. Ann sounded rather like Obi-Wan Kenobi instructing Luke Skywalker in the glories of his Jedi Knight heritage:

"To be black was to be the beneficiary of a great inheritance, a special destiny, glorious burdens that only we were strong enough to bear."[p. 51]

One implication of Ann’s line of thought is that the only explanation for why blacks, these embodiments of all the best values, weren’t rich and happy was, as Rev. Dr. Jeremiah A. Wright Jr. would point out to Obama many years later, that "white folks' greed runs a world in need." All that blacks needed to lead them to the wealth they deserved were audacious political leaders who had achieved "a higher form of power ," such as that nation-building statesman Barack Obama Sr.

Even as an ethnic activist in Chicago, the adult Obama still believed whole-heartedly in the image concocted by his mother of his father (who, in reality, had turned into an alcoholic blowhard):

"All my life, I had carried a single image of my father, one that I had sometimes rebelled against but had never questioned, one that I had later tried to take as my own. …It was into my father’s image, the black man, son of Africa, that I'd packed all the attributes I sought in myself, the attributes of Martin and Malcolm, DuBois and Mandela. … [M]y father’s voice had nevertheless remained untainted, inspiring, rebuking, granting or withholding approval. You do not work hard enough, Barry. You must help in your people’s struggle. Wake up, black man!" [p. 220]

Obama never quite got over his mother’s programming that 1) Being a politician, especially a politician who helps in his people’s struggle, is the highest calling in life, far superior to being some soulless corporate mercenary like her second husband; and 2) What blacks need is not more virtue, but better political leadership to achieve "a higher form of power ."

Or, in Obama’s case, the highest.

Barack Obama Sr. was the father whose dreams, as refracted through his mother’s urgings, have guided the politician’s life. But what were those dreams?

Dreams from My Father is a book about dreams and the methods for realizing those dreams. It offers an extended meditation on ends and means, although not in the usual sense of questioning whether the ends justify the means. Instead, Obama’s concern is whether the means facilitate the ends. Obama displays few doubts about the superior morality of his father’s putative goals, as conveyed by his mother: namely, the pursuit of power for the benefit of the black race. Racialism is simply a given to the memoirist.

As an adult, Obama slowly learns the hard truth: his father’s means had not been good enough.

In his subsequent life, the son, displaying admirable self-discipline, has methodically avoided exactly those things that thwarted his ambitious father: drunkenness, polygamy, boastfulness, imprudence, the Big Man syndrome (excessive generosity to impress distant relatives and hanger-ons), frankness, and marriage to white women.

We actually have a fairly good idea of what Barack Sr., a scholar both brilliant (he graduated summa cum laude from the U. of Hawaii in three years) and boastful, likely told Ann about politics and economics between the time he impregnated her when she was a 17-year-old coed and the time he left her when she was 20-year-old mother. Barack Sr. published in July 1965 a 5,400-word article called "Problems Facing Our Socialism" in the East African Journal, which was dug up in the UCLA library by Greg Ransom of PrestoPundit in 2008.

Barack Sr.’s first appearance on the historical stage was this reply to a famous paper by Tom Mboya, the pro-American Kenyan leader who was second to Jomo Kenyatta in influence. Mboya had advocated that the newly decolonized Kenya maintain an economic policy that was non-Marxist and non-ideological, with room for private enterprise, foreign investment, and protection of the property rights of whites and Asians .

Zaiki Laidi and Patricia Baudoin wrote in The Superpowers and Africa :

"The debates pitted the liberal internationalist Mboya against endogenous communitarian socialist Oginga Odinga and radical economists Dharam Ghai and Barrack [sic] Obama, who critiqued the document for being neither African nor socialist enough."

In Obama Sr.’s view, all of Mboya ’s errors were on the side of too little government control of the economy or too little expropriation of non-blacks .

Still, it’s possible to exaggerate Obama Sr. ’s leftism . He didn’t advocate eradicating all private enterprise. His concern was less with socialism v. capitalism than with blacks v. whites and Asians . Indians dominated small business in Kenya, and the elder Obama was not happy about it.

"One need not to be Kenyan to note that most hotels and entertainment places are owned by Asians and Europeans. One need not to be Kenyan to note that when one goes to a good restaurant he mostly finds Asians and Europeans …"

In his characteristic peremptory tone, Obama Sr. denounced Mboya’s proposed colorblind laws:

"How then can we say that we are going to be indiscriminate in rectifying these imbalances? … The paper talks of fear of retarding growth if nationalization or purchases of these enterprises are made for Africans. But for whom do we want to grow? Is this the African who owns his country? If he does, then why should he not control the economic means of growth in this country? It is mainly in this country one finds almost everything owned by non-indigenous populace. The government must do something about this and soon."

Yes, sir!

Obama Sr. didn’t seem to favor Marxist outcomes for the sake of Marxism, but because government control of the economy was most convenient for taking power and wealth from white and Asian businesses and giving it to blacks, especially to blacks of Obama Sr.’s tiny class of foreign-educated intellectuals. Thus, it might be more accurate to describe Obama Sr.’s ideology as "racial socialism." Like the more famous "national" variety of socialism, Obama Sr.’s version of socialism is less interested in ideology than in Lenin’s old questions of Who? Whom?

The apotheosis of this line of thought is seen today in Robert Mugabe’s economically desolate Zimbabwe.

In contrast to Obama Jr.’s intentionally occluded prose style, the confident tone of Obama Sr.’s 1965 paper is that of a bright young man sure that his target, Mboya, who merely happens to be the second most powerful man in Kenya, will of course appreciate 5,400 words of constructive criticism. It’s touching that Obama Sr. had this much faith in his country to utter such open and precise criticisms of his government’s economic and racial programs. Obama Jr. has never shown that faith in Americans.

In 1983, Obama graduated from Columbia in New York City, with plans to become a black activist. First, though, he'd work for a year in the private sector to save up. "Like a spy behind enemy lines," he takes a job with "a consulting house to multinational corporations." But capitalist temptation looms:

"… as the months passed, I felt the idea of becoming an organizer slipping away from me. The company promoted me to the position of financial writer. I had my own office, my own secretary, money in the bank. Sometimes, coming out of an interview with Japanese financiers or German bond traders, I would catch my reflection in the elevator doors — see myself in a suit and tie, a briefcase in my hand — and for a split second I would imagine myself as a captain of industry, barking out orders, closing the deal, before I remembered who it was that I had told myself I wanted to be and felt pangs of guilt for my lack of resolve." [p. 136]

In reality, even though Wall Street was booming when Obama graduated in 1983, he wound up in a job much crummier than he makes it sound in Dreams. He was actually a copy editor at a scruffy, low-paying newsletter shop, Business International. One of his co-workers, Dan Armstrong, blogged in 2005:

"I’m a big fan of Barack Obama … But after reading his autobiography, I have to say that Barack engages in some serious exaggeration when he describes a job that he held in the mid-1980s. I know because I sat down the hall from him, in the same department, and worked closely with his boss. I can’t say I was particularly close to Barack — he was reserved and distant towards all of his co-workers — but I was probably as close to him as anyone. I certainly know what he did there, and it bears only a loose resemblance to what he wrote in his book … ."

Armstrong, the former co-worker, went on to make a brilliant point about Obama’s autobiography that has eluded almost all professional pundits:

"All of Barack’s embellishment serves a larger narrative purpose: to retell the story of the Christ’s temptation . The young, idealistic, would-be community organizer gets a nice suit, joins a consulting house, starts hanging out with investment bankers, and barely escapes moving into the big mansion with the white folks. Luckily, an angel calls, awakens his conscience, and helps him choose instead to fight for the people."

Why did Obama feel "like a spy behind enemy lines" in his corporate job?

You have to understand the leftism inculcated in him by his mother. In Chicago, a few years later, Obama tries to work out why the blacks in the Altgeld Village housing project seem so much poorer morally than the economically poorer people he had known in Indonesia . Obama’s conclusion in 1995 was straight out of his mother’s playbook: global capitalism hadn’t chewed the Indonesians up and spat them out … yet. To demonstrate the influence of his mother’s economics on his thinking, I'll have to quote another sizable slab of Obama’s prose, engineered as usual to resist being quoted:

"I tried to imagine the Indonesian workers who were now making their way to the sorts of factories that had once sat along the banks of the Calumet River, joining the ranks of wage labor to assemble the radios and sneakers that sold on Michigan Avenue. I imagined those same Indonesian workers ten, twenty years from now, when their factories would have closed down, a consequence of new technology or lower wages in some other part of the globe. And then the bitter discovery that their markets have vanished; that they no longer remember how to weave their own baskets or carve their own furniture or grow their own food; that even if they remember such craft, the forests that gave them wood are now owned by timber interests … The very existence of the factories, the timber interests, the plastics manufacturer, will have rendered their culture obsolete; … Some of them would prosper in this new order. Some would move to America. And the others, the millions left behind in Djakarta, or Lagos, or the West Bank, they would settle into their own Altgeld Gardens, into a deeper despair." [pp. 183-184]

On the campaign trail, Obama’s more plain-spoken wife, Michelle, made clear the Obamas' anti-business attitudes:

"We left corporate America, which is a lot of what we are asking young people to do. Don’t go into corporate America. You know, become teachers, work for the community, be a social worker, be a nurse …. move out of the money-making industry, into the helping industry."

In Chicago, Obama was an interested observer of black separatists' calls for black capitalism.

On p. 200 of Dreams, Obama concedes the morality of the black nationalist case … in theory:

"If [black] nationalism could create a strong and effective insularity, deliver on its promise of self-respect, then the hurt it might cause well-meaning whites, or the inner turmoil it caused people like me, would be of little consequence." [p. 200]

Fortunately for the biracial and white-raised Obama and his ambitions for a career as a black leader, black separatism turns out to be a non-starter, economically and politically:

"If nationalism could deliver. As it turned out, questions of effectiveness, and not sentiment, caused most of my quarrels with Rafiq." [p. 200]

Obama dispassionately rejects Black Nationalism as impractical.

In the 1980s, Obama studies Black Muslim leader Louis Farrakhan’s newspaper (just as in 1995 he flew to Washington to attend Farrakhan’s Million Man March); over time, he notices that Farrakhan ’s Black Capitalist strategy isn’t working.

Initially, The Final Call is full of

"… promotions for a line of toiletries — toothpaste and the like — that the Nation had launched under the brand name POWER, part of a strategy to encourage blacks to keep their money within their own community . After a time, the ads for POWER products grew less prominent in The Final Call ; it seems that many who enjoyed Minister Farrakhan’s speeches continued to brush their teeth with Crest." [p. 201]

Obama has some fun imagining the frustrations of POWER’s product manager in trying to make and market a blacks -only toothpaste: "And what of the likelihood that the cheapest supplier of whatever it was that went into making toothpaste was a white man?"

The basic social problem that both Farrakhan and Obama want to alleviate is that, on average, blacks have less money than whites . Farrakhan’s plan to create a separate black-only capitalist economy in which blacks could not be cheated by whites out of the hard-earned wealth they would create is doubtful on various grounds. And even if it were plausible, it would require generations of hard work in dreary fields such as toothpaste -manufacturing.

In contrast, Obama’s plan to get more money for blacks from whites by further enlarging the already enormous welfare / social work / leftist charity / government / industrial complex is both more feasible in the short run, and, personally, more fun for someone of Obama’s tastes than making toothpaste would be . Obama’s chosen path involves organizing rallies, holding meetings, writing books, attending fundraising galas, giving orations, and winning elections. In these endeavors, insulting whites in the Black Muslim manner is counter-productive, because whites will have to pay most of the bills.

(This raises a question that never really seems to come up in Dreams. Would blacks getting a bigger slice of the pie through more effective political leadership be bad for whites ? Obama vaguely gestures a few times in the direction of his dreams from his father being somehow also good for whites, but it’s usually in a character-building, time-to-cut-your-cholesterol way.)

In sharp contrast to the financial failure of Farrakhan’s black capitalism, Obama followed a path of multicultural leftism lavishly funded by whites . In 1995, he was appointed chairman of the board of the Chicago Annenberg Challenge. Dreamed up in part by unrepentant leftwing terrorist William Ayers, the CAC gave away $50 million or so of Walter Annenberg’s arch-Republican money to "community organizations" in the name of improving public schools. It didn’t do anything for student test scores, but all those handouts made Obama a glamorous brand name among his political base: social workers and activists.

The climax of Dreams from My Father is Obama’s first trip to Kenya in 1988, between his community organizing gig and Harvard Law School. The trip got off to an angry start, what with all the white people he kept running into.

Initially, he stopped off for his three-week tour of the wonders of Europe that left him psychologically devastated:

"And by the end of the first week or so, I realized that I'd made a mistake. It wasn’t that Europe wasn’t beautiful; everything was just as I'd imagined it. It just wasn’t mine." [pp. 301-302]

Upon arrival, Obama tours Nairobi with his half-sister Auma . At the restaurant of the ritzy New Stanley Hotel, Obama experiences the same outrage as his father had 23 years before, when he complained in his anti-Mboya article, "when one goes to a good restaurant he mostly finds Asians and Europeans …" The son is annoyed that Kenya’s best restaurants are infested with white tourists:

"They were everywhere — Germans, Japanese, British, Americans … In Hawaii, when we were still kids, my friends and I had laughed at tourists like these, with their sunburns and their pale, skinny legs, basking in the glow of our obvious superiority. Here in Africa, though, the tourists didn’t seem so funny. I felt them as an encroachment, somehow; I found their innocence vaguely insulting. It occurred to me that in their utter lack of self-consciousness, they were expressing a freedom that neither Auma nor I could ever experience, a bedrock confidence in their own parochialism, a confidence reserved for those born into imperial cultures." [p. 312]

Obama and his sister are outraged when the black waiter gives quicker service to the white Americans sitting nearby. Auma complains:

"That’s why Kenya, no matter what its GNP, no matter how many things you can buy here, the rest of Africa laughs. It’s the whore of Africa, Barack. It opens its legs to anyone who can pay."

Obama reflects on his half-sister’s outburst:

"I suspected she was right … Did our waiter know that black rule had come? Did it mean anything to him? Maybe once, I thought to myself. He would be old enough to remember independence, the shouts of "Uhuru!" and the raising of new flags. But such memories may seem almost fantastic to him now, distant and naive. He’s learned that the same people who controlled the land before independence still control the same land … And if you say to him that he’s serving the interests of neocolonialism or some other such thing, he will reply that yes, he will serve if that is what’s required. It is the lucky ones who serve; the unlucky ones drift into the murky tide of hustles and odd jobs; many will drown." [pp. 314-315]

Mugabe couldn’t have put it better himself.

One subtle but telling difference between the views of Obama Sr. and Obama Jr. is that Asians play a realistically large role in the father’s feelings of envy. In contrast, the younger Obama’s ressentiment is simplistically black and white. In Dreams' conceptual framework, there are only three races: Black, White, and Miscellaneous. Despite all the years Obama spends in Indonesia and in heavily Asian Hawaii, Asians just don’t play much of a role in Obama’s turbulent emotions. He doesn’t take Asians personally, whereas everything about blacks and whites prods his most sensitive sores.

His half-sister Auma, on the other hand, has inherited Barack Sr.’s touchiness about Asians. She is incensed by both Nairobi ’s prosperous white tourists and its prosperous Indian shopkeepers:

"'You see how arrogant they are?' she had whispered as we watched a young Indian woman order her black clerks to and fro. 'They call themselves Kenyans, but they want nothing to do with us. As soon as they make their money, they send it off to London or Bombay. '" [p. 347]

While Obama Jr. agreed with Auma ’s diatribe against whites, he lectures her on her anti-Indian feelings:

"Her attitude had touched a nerve.'How can you blame Asians for sending their money out of the country,' I had asked her, 'after what happened in Uganda ?' I had gone on to tell her about the close Indian and Pakistani friends I had back in the States, friends who had supported black causes …." [p. 347]

He thinks about it further and decides that blacks and Asians are all just victims of The [White] Man behind the curtain:

"Here, persons of Indian extraction were like the Chinese in Indonesia, the Koreans in the South Side of Chicago, outsiders who knew how to trade and kept to themselves, working the margins of a racial caste system, more visible and so more vulnerable to resentment. " [p. 348]

Obama later learns that his half-sister Auma, who teaches German at the university, is trying to make something of herself, but her efforts to conserve her time and money for future investments elicit from her African kin

"… looks of unspoken hurt, barely distinguishable from resentment … Her restlessness, her independence, her constant willingness to project into the future — all of this struck the family as unnatural somehow. Unnatural…and un-African. It was the same dilemma … that certain children in Altgeld might suffer if they took too much pleasure in doing their schoolwork … " [p. 330]

For Obama, conveniently enough, there’s always one solution to any of the basic human conundrums: political power for his racial group.

"Without power for the group, a group larger, even, than an extended family, our success always threatened to leave others behind." [p. 330]

All this is not to say that Obama hasn’t changed his attitude toward economics (or race) since he published his autobiography in 1995.

Perhaps he has. In 2000, his dream of eventually winning the most powerful office in America plausibly attainable by a black leader qua black leader — Mayor of Chicago — was crushed when black voters rejected Obama in his primary challenge to Rep. Bobby Rush, a former Black Panther. Obama just wasn’t black enough to beat a more authentic black for the hearts of black voters. When he recovered psychologically after a year of mourning, he restyled himself as a black candidate who appeals to whites.

Maybe, deep down, Obama has changed his mind. Nobody, however, seems to have asked him.

In his 2004 Preface to the reissue of Dreams, the older Obama himself denies that he has gained much wisdom in subsequent years:

"I cannot honestly say, however, that the voice in this book is not mine — that I would tell the story much differently today than I did ten years ago, even if certain passages have proven to be inconvenient politically, the grist for pundit commentary and opposition research. " [p. ix]

This is a bad outlook for the American economy.

My reader’s guide to the President’s autobiography, America’s Half-Blood Prince: Barack Obama’s "Story of Race and Inheritance" is now on sale.