11/23/1987

Fortune, Nov 23, 1987

By David R. Henderson.

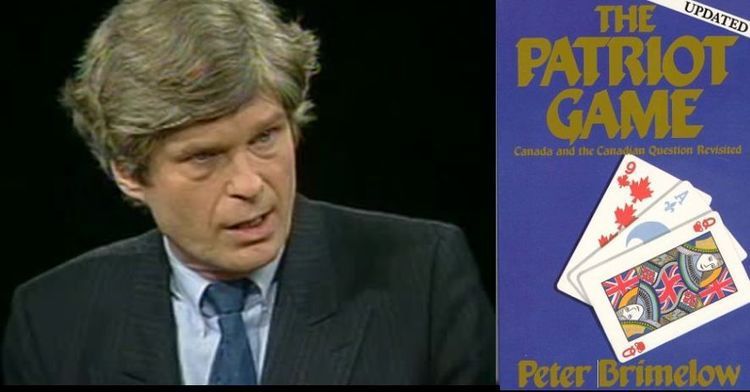

The patriot game; Canada and the Canadian question revisited.

What’s wrong with Canada? It is richer in resources on a per capita basis than the United States, spends much less on defense, and has no large underclass. Yet Canada’s standard of living is only about 70% of its southern neighbor’s and is probably headed lower. Peter Brimelow thinks he knows the answer.

Canada’s ''chronic underperformance,'' he writes in The Patriot Game (Hoover Institution Press, $26.95), is the result of ''a tangle of pathologies'' in Canadian politics.

Brimelow, who was born in Britain, spent seven years in Canada, and now lives in the U.S., tries to unravel this tangle. By and large he succeeds. One big problem, he argues, is extensive government intervention in the economy. One rough measure is government spending at all levels, which Brimelow says is 55% of gross national product. The figure on the U.S., hardly a laissez faire economy, is about 33%. Brimelow also points to specific government interventions that have made Canadians poorer. Tariffs on manufactured goods, he points out, protect Canadian manufacturers from foreign competition and make Canadian consumers pay higher prices.

Brimelow cites one study’s conclusion that trade barriers cost the average family in British Columbia, the westernmost province, more than $1,000 per year. Another heavy drain on the economy until recently, according to Brimelow, was government regulation and taxation of oil production and sales. Under former Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau, the government restricted the amount of oil and natural gas Western Canadian oil producers could sell abroad, diverting it instead at artificially low prices to Canadian consumers.

The Trudeau government also took a 25% share of all oil discoveries on public land, including those made by U.S. companies. The result was reduced oil exploration. Tight restrictions on investment by foreigners, writes Brimelow, are also hurting the economy. These explanations are neither new nor particularly controversial among mainstream Canadian economists. Take trade restrictions.

Canadian economists for years have blasted them for holding down Canada’s standard of living. Richard Harris, an economist at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, claims that Canada’s per capita income is 4% lower because of the country’s trade barriers. What is new — and certainly controversial — is Brimelow’s view of just how the Canadian political system went about creating this awful result. For those who wish to understand, The Patriot Game is must reading.

Brimelow’s basic argument is that 20th-century Canada is the creation of the Liberal party. Though out of power since 1984, the party has controlled the federal government for 66 of the past 91 years, and for 20 of the past 24.

It has managed that feat by uniting the French-speaking minority and dividing the English-speaking majority. The Liberal party gets virtually all its parliamentary seats from only two of Canada’s ten provinces: Ontario and Quebec.

The need for votes in Ontario explains why Liberal governments have had stiff tariffs on manufactured goods: Canada’s industrial heartland is in Ontario. It is no accident, as the Marxists say, that the current free-trade agreement is being negotiated while the Liberals are out of power and Brian Mulroney’s Progressive Conservatives are in.

Similarly, a look at the political map can explain Canada’s recent energy policies. The virtual absence of support from the four provinces west of Ontario, including the oil-producing provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan, meant that Liberals had little to lose politically by expropriating some of the Western oil producers' discoveries.

Where does Quebec fit in? To ensure support from French-speaking Quebecois, the Liberals have paid special attention to them. About every ten years, leadership of the party rotated between French and English: For example, in 1968 French-speaking Pierre Trudeau succeeded English-speaking Lester Pearson.

Quebec also gained from high tariffs, though to a lesser extent than Ontario. The separatist movement in Quebec, which began to grow in the 1960s, posed a threat to the Liberals. Without Quebec they would have to change their national strategy. They responded in the 1960s and 1970s by sending subsidies to Quebec and by imposing bilingualism on the rest of Canada.

THESE POLICIES, Brimelow states flatly, did not work. Separatism kept growing all through the 1960s and 1970s. In 1976 Rene Levesque’s separatist Parti Quebecois won the provincial election and stayed in power until 1985. And although Levesque’s 1980 referendum on separation was defeated by a 3 to 2 margin, notes Brimelow, ''Quebec is emerging as a genuine nation-state.''

Beginning in 1976, the Parti Quebecois, with wide assent from French-speaking people of all parties, imposed French as the only official language in Quebec. It is now illegal to use English signs in an English-language bookstore, to send your child to an English-speaking school (unless you or your spouse were educated in English in Quebec), or even to speak English at work.

Brimelow foresees more trouble ahead. He argues that Canada’s new constitution, adopted in 1982, seems to forbid precisely what the Quebec government is doing, which is why Levesque was the one provincial premier who refused to agree to it. If Quebec’s language laws are ever tested, Brimelow believes the court will have to overturn them or ignore the constitution. If the laws should be overturned, separatism would likely blaze anew.

NOT TO BE MISSED in the tangle of pathologies is Canada’s New Class. The term, which Brimelow borrows from Irving Kristol, refers to Canada’s civil servants, academics, writers, and journalists, who have a disproportionate influence on public discussion. There are two important strands to the New Class’s ideology. The first is belief in substantial government intervention.

Brimelow notes that Canada’s New Class has been more successful than its U.S. counterpart. One reason, he notes, is that Canadian civil servants are much more powerful than their U.S. cousins: Canada’s equivalent of assistant secretaries and under secretaries are career civil servants who keep their jobs when a new government comes to power.

In Washington, they come and go with each new Administration. The second and more recent strand of New Class ideology is Canadian Nationalism. Brimelow capitalizes ''nationalism'' because he sees it as a cover, the ''patriot game'' of the book’s title. A cover for what? For special interest legislation. Among nationalism’s most significant beneficiaries, Brimelow points out, are Canada’s publishers and authors, protected by ''Canadian content'' rules from having to go up against U.S. competitors.

You might think that Brimelow is pessimistic about Canada’s chance of casting off the interventionist baggage and becoming wealthier. He’s not. Brimelow argues that separatism could be a solution for English Canada as well as for Quebec. At some point, he argues, English Canada will assert its North American identity, and might even wish to expel Quebec. Brimelow builds a plausible scenario under which a split between English Canada and Quebec causes both to have closer economic ties to the U.S. Result: more trade and more wealth. Like all wise forecasters, though, Brimelow hedges: Canada, he writes, could ''blunder on … for a long time.''