THE WAGES OF CUCKSERVATISM: France’s Marine Le Pen Moved Left, Provoked Crippling Challenge From Eric Zemmour

03/12/2022

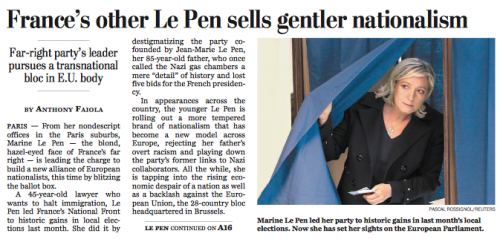

Above: Marion Maréchal, Marine Le Pen’s niece, joins Éric Zemmour’s presidential campaign, March 12, 2022.

And they’re off! French President Emmanuel Macron officially announced on March 3 that he is running in this year’s presidential elections. Meanwhile the two main immigration patriot candidates, Marine Le Pen and Éric Zemmour, have both qualified to run in the election by each securing over 500 supporting signatures from mayors and other elected officials. Phew!

Zemmour’s qualifying was far from certain, since the identities of the signatories must now — since a reform by the previous president, the non-entity François Hollande — be made public, opening them up to social opprobrium. (In 2016, this Managed Democracy technique was key to stopping American Renaissance editor Jared Taylor from running against a RINO in Virginia’s Tenth Congressional District, where he lives.)

The first round of this election will be on April 10. So the next question now: Who will face the centrist Macron in the second-round presidential election on April 24?

There is still an off-chance that the vacuously amorphous “conservative” candidate, Valérie Pécresse, will make it. But let’s put that uninspiring possibility aside.

Marine Le Pen in general has polled better than Zemmour, though he was neck-and-neck with her in second half of February. But a lot can happen between now and the first-round voting on 24 April. And the fact is that she should not be in this position — she should not have made it possible for a significant challenger to emerge on her right.

Significantly, Marine Le Pen’s party, the National Rally (Rassemblement National or RN — she changed its name after the 2018 Presidential election) has been bleeding out personalities to Zemmour’s Reconquest party. The list of RN defections to Zemmour grows ever-longer: Senator Stéphane Ravier, four Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) — Nicolas Bay, Gilbert Collard, Maxette Pirbakas, and Jérôme Rivière — and the identitarian social media maven Damien Rieu. These figures are little-known outside of France, but many have been important in the French nationalist scene. Another example of Zemmour’s superior ability to unite the conservative and nationalist rights: two national MPs, Guillaume Peltier and Joachim Son-Forget, have defected to Reconquest from the conservative and centrist parties.

Perhaps symbolically the most important loss came from Marine Le Pen’s own family. Marion Maréchal, her attractive 32-year-old niece, recently joined Zemmour’s movement at a spectacular March 6 rally in Toulon. She justified her move saying:

I am convinced Éric Zemmour is the best positioned in this presidential election. This is not a matter of polling but of political vision. Politics is about energy [c’est une dynamique] … The continuity and unity of the French nation is at stake in this election. If we do nothing, in just a few years, our children could wake up in a France who would have the same name but would no longer be the same person. … I am here because, like you, I am convinced that the cultural and demographic question is the priority.

« Je suis convaincue qu’@ZemmourEric est le mieux placé dans cette présidentielle.

— Marion Maréchal (@MarionMarechal) March 6, 2022

Ce n’est pas une question de sondage mais de perspective politique. La politique, c’est une dynamique, c’est une relation de confiance qui se tisse avec les Français ! » #ZemmourToulon pic.twitter.com/M9swskZAg6

Maréchal, by the way, still knows how to work her magic. She said, for instance:

The European Union has become a vast camping ground for migrants, a store front for Chinese products, an incubator for supposedly progressive insanities, torn between veiled women and “pregnant” men.

« L’Union européenne est devenue un vaste camping pour migrants, une arrière-boutique pour produits chinois, un incubateur pour délires prétendument progressistes entre femmes voilées et hommes « enceints ». » #ZemmourToulon pic.twitter.com/P02J93N9qL

— Marion Maréchal (@MarionMarechal) March 6, 2022

Maréchal hasn’t been directly active in politics since the 2018 presidential election, preferring to run a private political science school in Lyon, and she has not been part of the RN since 2017.

Marine Le Pen’s own father, the venerable nationalist patriarch Jean-Marie Le Pen, now 93 years old, whom she actually expelled from the party he founded as part of her move to the center, had been making ambiguous statements. Occasionally, he seemed to favor Zemmour or, at the least, whichever candidate has the better chance of winning the second round. (However, he recently came down in favor of his daughter [Présidentielle: Jean-Marie Le Pen juge "choquant" un ralliement de Marion Maréchal à Éric Zemmour, BFMTV.com, Jan 30, 2022].)

What are the causes of Marine’s losses in the nationalist camp and Zemmour’s rise as a challenger? These are many and interrelated — and they have relevance to Donald J. Trump’s ability to retain his hold over the GOP base.

Marine Le Pen’s entire political strategy since she was handed control over her father’s party in 2011 has been to avoid the various French Establishment taboos periodically violated by her father: Marshal Philippe Pétain’s not being a traitor, the place of the Holocaust in world history, the existence of race, and so on. In other words, she cucked.

Jean-Marie Le Pen was not necessarily being a gratuitous provocateur, as many people think, but making nuanced comments, albeit often incidentally. And he was simply willing to censor himself for the sake of impudent journalists.

Marine, by contrast has spent a decade honing a very particular position: civic nationalist, opposed to immigration but inclusive of Islam, protectionist, economically left-wing, and socially moderate (e.g., not opposed to gay marriage). In the days of the euro crisis, she was also in favor of leaving the European common currency and restoring the French franc, but she has since quietly backed down from this position.

These positions have made Marine Le Pen more popular with less well-off working class or unemployed Frenchmen. However, they have left her open to challengers, like Zemmour, articulating a more hardline position on race and Islam, and with economic policies more compatible with mainstream conservative right-wing voters. Significantly, Zemmour polls better among older people and the more educated.

Perhaps Marine Le Pen’s most significant retreat has been her denial of the existence of the Great Replacement — the large-scale substitution of the French population by immigrants, in particular Africans and Muslims. In 2014, she agreed with the French Regime Media that the Great Replacement was a mere “conspiracy theory” [Pour Marine Le Pen, la théorie du «grand remplacement» relève du «complotisme», Le Figaro, November 2, 2014]. In 2019, she implausibly claimed that she “didn’t know about” the Great Replacement [« Je ne connais pas cette théorie du “grand remplacement” » : l’amnésie de Marine Le Pen, Le Monde, March 18, 2019].

All this is rather tiresome when any tourist can see that the populations of just about all Western European cities are changing before our very eyes. In neighboring Belgium, which has similar demographics to France, official statistics indicate, already, that barely half of births are to native Belgian mothers [Great-Replaced: Half of Newborns in Belgium Have Foreign-Origin Mothers, by Guillaume Durocher, Occidental Observer, December 23, 2021] (note: the “non-Belgian” births include those of European immigrants. Africans and Muslims probably make up a third of births in Belgium). On the Great Replacement, the Regime Media is shamelessly engaged in misrepresentation of reality worthy of Pravda.

Zemmour, by contrast, has made explicit opposition to the Great Replacement the central plank of his entire campaign. His is an ambiguous position: at once an avowed civic nationalist (he himself, after all, is an “assimilated” Sephardic Jew of North-African extraction), a recognition of the importance of the white native French as the nation’s ethnic core, and an opposition to public manifestations of Islam.

Most recently, desperate to discredit Zemmour, Marine Le Pen claimed “Nazis” supported the North African Jew, whereas she by contrast had thoroughly cleansed her own party of such tendencies. This unprincipled and counterproductive recycling of Regime Media slander was the last straw for many people.

I have written elsewhere on the assets that have made Zemmour’s campaign possible: his long experience as a combative conservative Talking Head (c.f. Tucker Carlson — or Pat Buchanan in 1992); his relative independence as a bestselling author; and his enjoying the support of an important French (non-Jewish) media mogul, Vincent Bolloré [Éric Zemmour on the Cowardice of French Elites, by Guillaume Durocher, American Renaissance, January 28, 2022].

It is not so much that Marine Le Pen has given up on her core positions in general, especially on immigration. She is very similar to Zemmour: both want to eliminate family reunification and Birthright Citizenship, and to deport foreign criminals, and reduce (non-EU) immigration to negligible levels. Zemmour has suggested a €10,000 baby bonus for each child for rural families, a measure transparently aimed at increasing the native white birth rate. Le Pen has been more open to hosting Ukrainian refugees than Zemmour, sharply distinguishing them from Africans and Muslims.

Nevertheless, there is simply a palpable difference in the dynamic between her and Zemmour’s campaigns. Marine’s career has advanced by backing down from certain controversial positions, Zemmour’s career has advanced by always pushing the envelope. Even now, Zemmour will defend Marshal Pétain (pointing out, as a good civic nationalist, that he did not deport French Jews) and stress the importance of abolishing France’s draconian censorship legislation against “Hate Speech.” Another example of Zemmour’s superior ability to unite the conservative and nationalist rights.

Zemmour’s support does seem to have stalled since February, perhaps because the novelty factor was wearing off, or because the relentless attacks on him as a misogynist are working, as they supposedly did against Pat Buchanan. Zemmour has indeed said a lot of things over the years, but he at 63 is the kind of misogynist who has just fathered a child with his 28-year-old mistress. (This is France.) The Russia-Ukraine conflict is a problem — he in the past has been very pro-Russian, but then again so has Le Pen.

“This is France” applies to politics too. Note that Le Pen had already moved to the left on economic and social issues, as many America Firsters urge their movement. But the result is that Zemmour is tapping into older and middle-class voters, particularly those who might have voted conservative, i.e., voters fearful of Le Pen’s socialistic and (previously) anti-euro economic policies or who were simply put off by the Le Pen brand name.

These voters almost certainly will be united in the second round, as long as a nationalist candidate makes it: e.g., this poll from January finds that if Zemmour is in second place, 84% of Le Pen voters would vote for him: Baromètre de l'élection présidentielle — Vague 8 — IFOP, January 3, 2022. That’s probably similar for Zemmour voters supporting Le Pen in the second round. Zemmour, however, is much better placed to unite the right in terms of political figures: he has been poaching both nationalist (Rassemblement National) and conservative (Les Républicains) politicians.

One thing is certain: the polls show that there’s a lot of immigration patriotism in France. Even the center-right Les Republicains’ Valérie Pécresse has made strikingly fierce noises about immigration [In a France Fearful of Immigrants, Another Candidate Tacks Hard Right, by Norimitsu Onishi, NYT, December 18, 2021].

J’éradiquerai les zones de non-France.

Je serai toujours du côté des riverains et des victimes. Commettre un délit dans un quartier dit "de reconquête républicaine" sera une circonstance aggravante. #DébatdelaDroite pic.twitter.com/DP3iz9IgNm

— Valérie Pécresse (@vpecresse) November 14, 2021

It’s too bad they couldn’t have united in the first round.

My view on the polls: things can and will still change. The energy among activists is clearly with Zemmour, witness the numerous political defections to his campaign and the huge number of activists joining his party Reconquest (over 100,000 members since its foundation 3 months ago).

There are also internal factors within Le Pen’s RN which have led it to bleed out personnel over the years. Many complain of Marine’s stifling management of the party, dominated (I quote an insider) by a “a clique of homosexuals.” She does not tolerate the existence of different “tendencies” within the party, e.g., of personalities of a more free-market or socially conservative bent.

And, plainly, the party has simply underperformed in recent years. During the disappointing 2017 presidential elections, Marine did poorly both in the televised debate with Macron and at the ballot box (33.9% of the final vote). Party spokesperson Florian Philippot — a civic nationalist who was once Marine’s closest protégé — ignominiously left the movement shortly thereafter. He has since converted himself into an anti-COVID–measures activist and all-purpose contrarian.

While the RN did well in the 2019 elections to the European Parliament (winning 23 out of 79 French seats), the party did poorly in the 2020 municipal and 2021 regional elections, failing to finish first in a single region.

It is still too early to say who will face Macron in the second round and it would be wrong to deny Marine Le Pen’s own assets. She has the experience of two previous presidential campaign. By contrast, Zemmour is of course still finding his feet on occasion.

But if Le Pen does reach the second round, I personally am convinced she will lose. Hers has long been a joyless struggle.

Zemmour by contrast has that Trumpian je ne sais quoi: the daring thrill and momentum of which great upsets are made.

Guillaume Durocher [Tweet him] is a European historian and political writer.