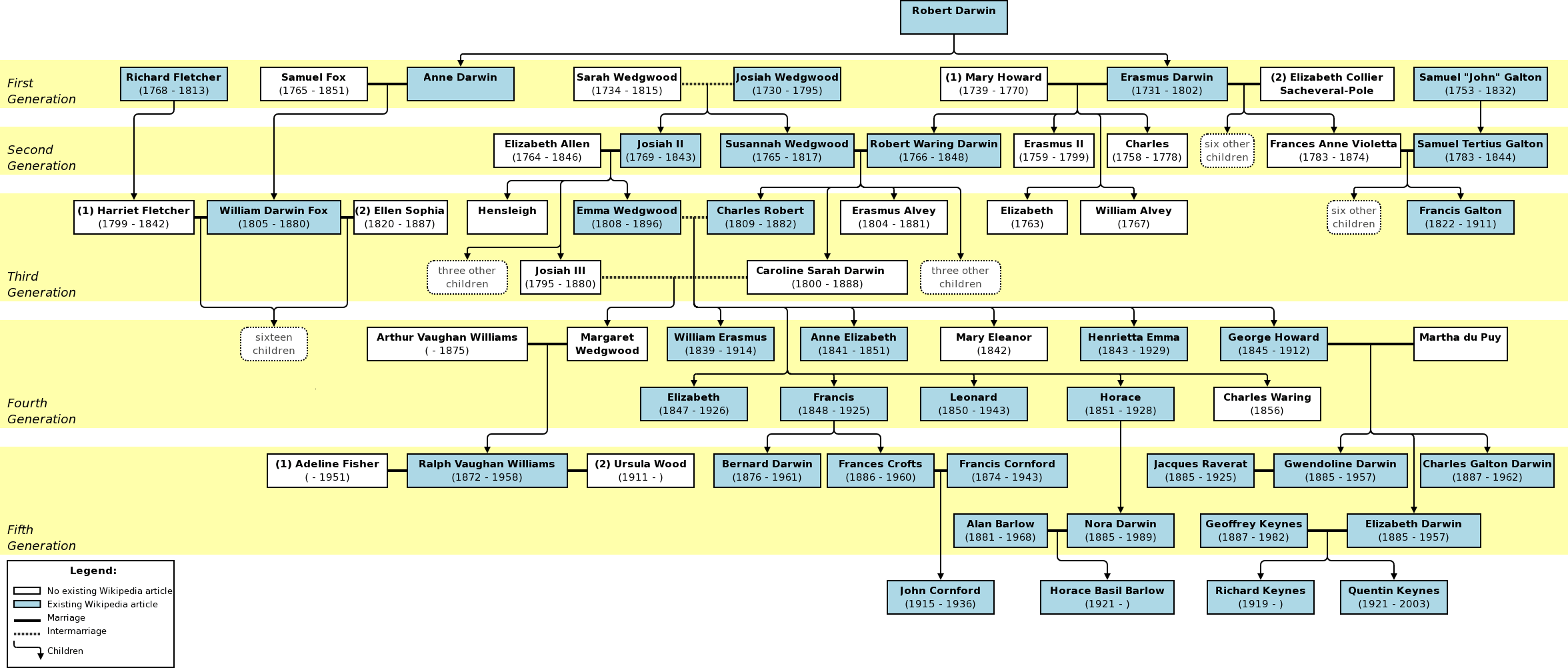

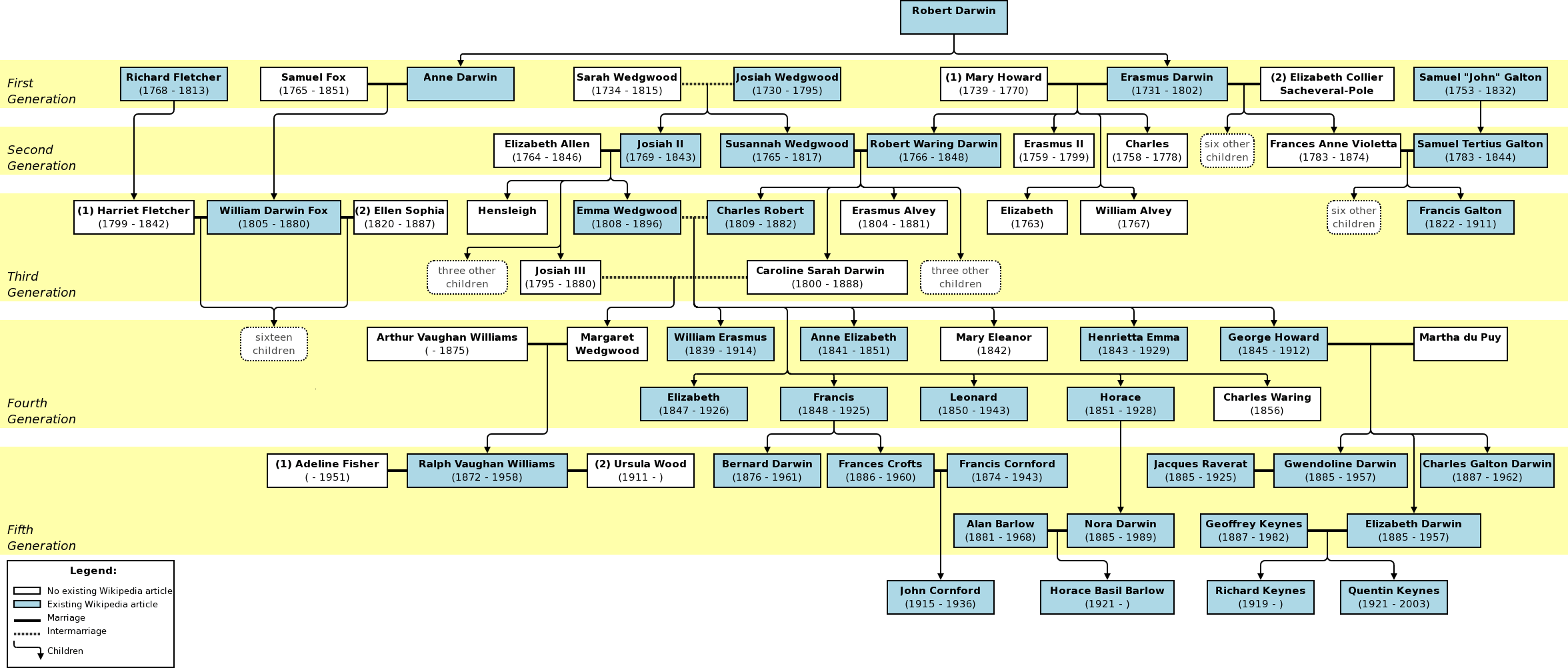

Here, Wikipedia provides a typical family tree with Darwin in the fourth row center. You can click on this yellow and blue image to see a larger, more legible version, but it’s still a seemingly shapeless mess.

By Steve Sailer

08/05/2007

Genealogy — the study of who a person’s ancestors are — is viewed by American intellectuals as a quaint hobby of only individual interest. But it’s actually one of the most under-explored paths to better understanding humanity.

So I was quite pleased to see the cover story in the August 6, 2007 issue of The New Republic, "The Genealogy Craze in America: Strangled by Roots" [Free registration required, or read it here.] by Steven Pinker, the Harvard psychologist and author of the outstanding 2002 bestseller The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature.

Pinker has become perhaps the pre-eminent spokesman for the human sciences. His next book, The Stuff of Thought: Language as a Window Into Human Nature, will be out in September.

I was especially happy because Pinker’s article cogently articulates many of the ideas about the overlooked importance of kinship that he and I kicked around via email in the late 1990s, and which have provided the basis for many of my VDARE.com articles ever since.

In The New Republic, Pinker graciously credits me with having forecast the present chaos in Iraq:

"In January 2003, during the buildup to the war in Iraq, the journalist and blogger Steven Sailer published an article in The American Conservative in which he warned readers about a feature of that country that had been ignored in the ongoing debate. As in many traditional Middle Eastern societies, Iraqis tend to marry their cousins. About half of all marriages are consanguineous [between first or second cousins. A second cousin is someone who shares a great-grandparent] … The connection between Iraqis' strong family ties and their tribalism, corruption, and lack of commitment to an overarching nation had long been noted by those familiar with the country. … Sailer presciently suggested that Iraqi family structure and its mismatch with the sensibilities of civil society would frustrate any attempt at democratic nation-building."

Pinker also notes how little highbrow thought is given to genealogy these days:

"For all its fascination, kinship is a surprisingly neglected topic in the behavioral sciences. A Martian reading a textbook in psychology would get no inkling that human beings treated their relatives any differently from strangers. Many social scientists have gone so far as to claim that kinship is a social construction with no connection to biology."

In reality, we more easily team up with our relations:

"… blood relatives are likely to share genes. To the extent that minds are shaped by genomes, relatives are likely to be of like minds. Close relatives, whether raised together or apart, have been found to be correlated in intelligence, personality, tastes, and vices.

This has profound social and political consequences:

"The overlap of genes among relatives does more than make them similar; it … sets the evolutionary stage for feelings of solidarity and affection at the emotional level, and that in turn shapes much of human life. In traditional societies, genetic relatives are more likely to live together, work together, protect each other, and adopt each other’s orphaned children, and are less likely to attack, feud with, and kill each other."

Despite its tremendous predictive power, the genealogical perspective hasn’t caught on in academia. Why not?

One technical issue that confuses people: you need to be able to picture family trees in your head. Yet, the messy-looking family tree loaded with nephews and cousins that your uncle sends you in his Christmas card gives the wrong impression. To be able to generalize about genealogy, you need to imagine a cleaner, more abstracted diagram of your relation to your biological ancestors.

Let’s take a look at a two different types of family tree for, appropriately enough, Charles Darwin’s family.

The Darwin clan has maintained a level of distinguished achievement from the 18th Century into the 21st that few other families can match, furnishing ten Fellows of the famous Royal Society of scientists over six straight generations.

Here, Wikipedia provides a typical family tree with Darwin in the fourth row center. You can click on this yellow and blue image to see a larger, more legible version, but it’s still a seemingly shapeless mess.

While disorderly, this common format is highly informative. It shows some of Darwin’s many illustrious relatives, such as his grandson Bernard Darwin, a lawyer who pioneered golf writing in the London Times, his great-nephew Ralph Vaughn Williams, the admired composer, and, most relevantly, his half-cousin Sir Francis Galton, the polymath who founded, among much else, the scientific study of human heredity.

Galton was perhaps inspired to begin his inquiry into Hereditary Genius (the title of his pioneering 1865 book) by the fact that the one grandparent he shared with his famous cousin was Erasmus Darwin, who had been the most noted doctor in England and a prominent intellectual.

Still, for all the richness of its content, few could glance at this convoluted diagram and be reminded of such simple truths as that everybody has two parents, four grandparents, eight great-grandparents and so forth.

In contrast, here is a schematic of the family tree of Charles Darwin and his forebears as the scientist himself might have pictured it:

|

16 |

8 |

4 |

2 |

1 |

|

William Darwin |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Robert Darwin |

|

|

|

|

Anne Waring |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Erasmus Darwin |

|

|

|

John Hill |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Elizabeth Hill |

|

|

|

|

Elizabeth Alvey |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Robert W. Darwin |

|

|

Charles Howard |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Charles Howard |

|

|

|

|

Mary Bromley |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mary Howard |

|

|

|

Paul Foley |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Penelope Foley |

|

|

|

|

Elizabeth Turton |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Charles Darwin |

|

Thomas Wedgwood |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Thomas Wedgwood |

|

|

|

|

Mary Leigh |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Josiah Wedgwood |

|

|

|

? |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Mary Stringer |

|

|

|

|

? |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Susannah Wedgwood |

|

|

Thomas Wedgwood |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Richard Wedgwood |

|

|

|

|

Mary Hollins |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sarah Wedgwood |

|

|

|

? |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Susan Irlam |

|

|

|

|

? |

|

|

|

|

(Of course, while everybody has this same structure of ancestors, the number of descendents differs wildly. Darwin, for instance, had ten children. Thus, family trees of descendents can’t be standardized.)

Despite the elegance of this schematic, some problems inherent in the study of ancestry leap out.

First: few people know every name in their family tree back more than a few generations.

Darwin is one of the more famous men in history, and he lived in a culture obsessed with pedigree. He himself came from eminently respectable stock — besides his famous paternal grandfather, Erasmus Darwin, his maternal grandfather Josiah Wedgwood founded in 1759 what remains today the most famous brand name in fine china.

And yet, by the time we go back four generations, we only know the names of 12 of Darwin’s 16 great-great-grandparents. Another generation back, and we are missing 14 of the 32 names, including one on the more traditionally posh paternal side of his family.

Second: cousin marriage is not exclusively confined to the Middle East.

Darwin’s grandfather Josiah Wedgwood, the great potter, married Sarah Wedgwood, a third cousin. (Darwin himself married Emma Wedgwood, his first cousin. Unsurprisingly, their children were sickly and/or brilliant.)

Third: the sheer number of direct biological ancestors becomes mentally overwhelming the farther back you go in your family tree.

Ten generations in the past (at 25 years per generation, that’s about 250 years ago), your family tree has 1024 slots to fill. That’s too large a number for most people to deal with. So, genealogists try to simplify ancestry, often by just tracking the surname through the direct male lineage. By way of illustration, the Darwin family name has been tracked back to William Darwin who died in 1542.

Beyond ten generations ago, the ancestor overload keeps getting worse, doubling with each generation. Twenty generations ago, you had room for 1,048,576 ancestors — a meg. Thirty generations — a gig. Forty generations (roughly around 1000 AD), you had more than a trillion openings for ancestors.

As Pinker explains:

"But the fact that our ancestors never covered the surface of the Earth ten deep shows that medium-distant-cousin marriages must have been the rule rather than the exception over most of human history… "

For example, due to Darwin’s Wedgwood grandparents being third cousins, the 64 slots in his family tree six generations before him were filled by only 63 separate people, with one Wedgwood doing double duty.

Because travel was so slow in the past, even in cultures that didn’t endorse cousin marriage a boy was more likely to marry the girl next door. So, couples often ended up related to each other by many genealogical pathways that added up to the equivalent of being a close relation.

Anthropologist Robin Fox, author of the classic Kinship and Marriage, observed:

"If we could only get into God’s memory, we would find that eighty per cent of the world’s marriages have been with at least second cousins. In a population of between three and five hundred people, after six generations or so there are only third cousins or closer to marry. During most of human history, people have lived in small, isolated communities of about that size, and have in fact probably been closer to the genetic equivalent of first cousins, because of their multiple consanguinity."

Sounds creepy. But Pinker says:

"This chronic incest, by the way, did not turn our ancestors into the cast of Deliverance. The degree of relatedness, and hence the risk that a harmful recessive gene will meet a copy of itself in a child, falls off a cliff as you move from siblings to first cousins to more distant cousins."

If you could plot the actual unique individuals in your family tree, they would initially fan out into the past, doubling with each generation, just like the number of slots in the family tree. But at some point in the past, the number of individuals would start to get fewer in number, ultimately forming a diamond-shaped rather than fan-shaped family tree. Genealogists label this "pedigree collapse".

Demographer K.W. Wachtel estimated that an Englishman born in 1947 would have had two million unique ancestors living at the maximum point around 1200 AD, 750 years before. There'd be a billion open slots in the family tree in 1200, so each real individual would fill an average of 500 places. Pedigree collapse would set in farther into the past than 1200.

Pedigree collapse delivers a profound implication about how the biology of race is rooted in the biology of family, even though so many fashionable thinkers today claim race doesn’t even exist. (But in my Random House Webster’s College Dictionary, the first definition of "race" is "1. A group of persons related by common descent or heredity," so it’s hard to see how it can’t exist.)

Why only two cheers? Because, unfortunately, Pinker tries to avoid discussing the relation between genealogy and race. So his New Republic article is ultimately misleading.

Pinker echoes Steve Olson, author of Mapping Human History, who claims that everybody living today has a common ancestor within the last few thousand years. Pinker writes:

"The same arithmetic that makes an individual’s pedigree collapse onto itself also makes everyone’s pedigree collapse into everyone else’s. We are all related–not just in the obvious sense that we are all descended from the same population of the first humans, but also because everyone’s ancestors mated with everyone else’s at many points since that dawn of humanity. … a single mating between people from two ethnic groups results in all their descendants being related to both groups in perpetuity.

Well, that’s one way of looking at it. But the two Steves are getting themselves bogged down in essentially symbolic thinking — in which having one ancestor from racial group X is seen as in some way just as important as having millions of ancestors from racial group Y.

Ironically, Pinker makes gentle fun of genealogy hobbyists for getting excited about finding that they are distantly related to famous people:

"And before you brag about the talent or courage you share with some illustrious kinsman, remember that the exponential mathematics of relatedness successively halves the number of genes shared by relatives with every link separating them. You share only 3 percent of your genes with your second cousin, and the same proportion with your great-great-great-grandmother."

But exactly the same math explains why intellectuals shouldn’t get so excited about the fact that, say, tens of millions of white people in America are a tiny bit black. Neither means much.

The more significant insight we can garner from the necessary existence of pedigree collapse is not that everybody is related to everybody else, but that every person is much more related to some people than to other people.

Say that we somehow knew the name of every single ancestor of Charles Darwin who was alive 750 years before his 1809 birth. And say that, somehow or other, one of Darwin’s two million unique ancestors who populate the one billion open slots in his family tree was, say, n!Xao, a Bushman of the Kalahari Desert, from whom he was descended by one pathway.

That would certainly be interesting. But it wouldn’t be important in determining Darwin’s genetic makeup — because he'd also turn out to be descended from, say, William, a farmer in Wessex, by 500 different paths.

And then there would be Catherine and John and Ann and Mary and …

Add them all up and, yup! Darwin would be, for all practical intents and purposes, English rather than Bushman.

As I reported earlier this year in VDARE.com, Oxford population geneticist Bryan Sykes estimates that the ancestors of living natives of the British Isles arrived there, on average, an astonishing 8,000 years ago, or 320 generations. Back that far, Darwin’s family tree would have an unthinkably large number of slots to fill — a number with 96 zeros — but the number of unique individuals would be quite small.

In other words, we can be sure that Darwin was, for all practical purposes, racially English.

And that’s what’s missing from Pinker’s otherwise superb article: an explanation of how kinship means not just family, but race.

As we've seen, pedigree collapse implies that when you go back enough generations, inbreeding become the overwhelming fact of genealogy.

And, as I pointed out in VDARE.com in 2002 in "It’s All Relative: Putting Race in Its Proper Perspective," the most useful definition of a racial group is "a partly inbred extended family".

Sure, the genealogical relationships between two random members of a racial group are usually not close. But they are numerous enough that they sum up to a sizable amount.

We can see these hereditary similarities within races all around us. The genetic anthropologist Henry Harpending of the U. of Utah has pointed out that if he had never met his grandchildren before, he'd have a hard time picking them out by sight from the other children playing on the street. Yet, he'd have very little difficulty visually distinguishing children by race.

|

|

Let’s try this experiment with Darwins. On the left is Charles Darwin and on the right is his beloved grandson Bernard Darwin, the golf journalist. Notice the Darwin family genes?

Well, uh … maybe …

Perhaps you could pick Bernard out as Charles' grandson if you had enough pictures, but what is more immediately evident is that, genetically speaking, they're a couple of white guys.

According to Harpending’s genetic math, on average, people are as closely related to other members of their subracial "ethnic" group (e.g., Japanese or Italian) versus the rest of the world as they are related to their grandchildren or nephews and nieces versus the rest of their ethnic group.

That’s highly important to understanding how the world works.

With that caveat registered, let’s let Pinker have the last word:

"… the almost mystical bond that we feel with those whom we perceive as kin continues to be a potent force in human affairs. It is no small irony that in an age in which technology allows us to indulge these emotions as never before, our political culture systematically misunderstands them."

This is a content archive of VDARE.com, which Letitia James forced off of the Internet using lawfare.