What McVeigh Meant

By Sam Francis

05/14/2001

For all the fun and frolic that the nation’s media elite was enjoying over the now-delayed execution of Timothy McVeigh, there remains a nagging question in their minds about the Oklahoma City bombing that McVeigh now openly admits having committed: Why doesn’t this terrorist feel any guilt?

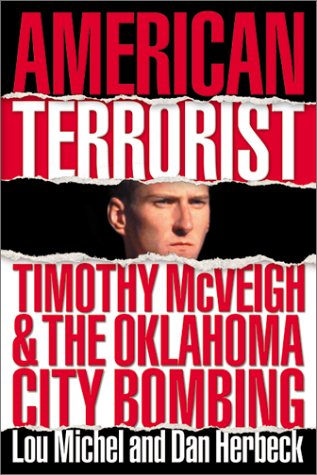

The question permeates the best-selling examination of the bombing and the bomber, American Terrorist: Timothy McVeigh and the Oklahoma City Bombing, by Buffalo News reporters Lou Michel and Dan Herbeck, and it pops up at the end of the series of letters that McVeigh wrote to yet another journalist, Phil Bacharach, published in Esquire this month. (RealAudio interview with Bacharach, 30 min.)

Indeed, in both the book and the letters, McVeigh, guilty of the largest mass murder in American history, is also probably the cheeriest murderer in all of history. In the letters to Mr. Bacharach, he is mainly concerned about the movies and TV shows he’s been watching (his favorite seems to be Clint Eastwood’s "Unforgiven," but he didn’t much care for "Seinfeld").

As for the bombing, he shows no remorse, regret or guilt whatsoever; he’s referred to the day care center and the children he slaughtered in the Murrah Building as "collateral damage" and compared all his innocent victims to the imaginary bad guys of "Star Wars." As Mr. Bacharach himself concludes his article, "It is beyond me to reconcile the Timothy McVeigh who murdered 168 people with the writer of these letters … . I do know one thing: In the written word, at least, he has not a whisper of conscience."

Is that because McVeigh is a "psychopath" or "sociopath" or fits some other psycho-babble label invented to explain the unexplainable? Probably not. The psychiatrist who studied him in prison doesn’t use such terms but has no better explanation himself. Moreover, McVeigh has always claimed he didn’t know the day care center was there, that it wasn’t visible from the street, that he would have picked another target if he had known, that he tried to avoid harming non-government employees.

Most of that, of course, doesn’t help. Even if the day care center hadn’t been there, the bombing was still more brutal than most people could ever imagine committing. And McVeigh really didn’t try very hard to avoid "innocent" casualties. Any federal building is full of people who have nothing to do with the federal government McVeigh hates so much — taxpayers, crime victims, veterans, maybe even men like David Koresh of Waco or Randy Weaver of Ruby Ridge trying to extract a little justice for themselves. It didn’t matter very much to Timothy McVeigh that he blew these kinds of good people up along with the bureaucrats, and it doesn’t matter to him now.

But the reason it doesn’t matter to him ought to be pretty clear from what he tells Mr. Michel and Mr. Herbeck and from what he’s written to Fox News reporter Rita Cosby. Timothy McVeigh thinks of himself as a soldier fighting a war, and he has no more conscientious reaction to killing civilians, government employees or not, than Allied airplane pilots had in World War II when they firebombed Japanese and German civilians in Tokyo, Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and Dresden, or American pilots when they hit civilian targets in Vietnam, Iraq and Serbia.

"Bombing the Murrah Federal Building," McVeigh writes to Miss Cosby, "was morally and strategically equivalent to the U.S. hitting a government building in Serbia, Iraq or other nations. Based on observations of the policies of my own government, I viewed this action as an acceptable option. From this perspective, what occurred in Oklahoma City was no different than what Americans rain on the heads of others all the time and, subsequently, my mindset was and is one of clinical detachment."

"Clinical detachment" may not be an accurate description of how many American soldiers and airmen regard the killing of civilians, but it’s probably true that most who have killed civilians don’t agonize about it very much, and some (like those who to this day celebrate Arthur "Bomber" Harris, who led the murderous destruction of Dresden from the air two months before the end of World War II in Europe) go to their graves proud of it.

To understand why McVeigh feels no guilt for what he did is not to say that he shouldn’t. What he did was indeed an act of mass murder that deserves death, if not a good deal more than death. But the point he tried to make in his act of murder remains a serious one — that in modern warfare as practiced routinely and happily by the United States and other modern democracies and increasingly in law enforcement, civilian targets and civilian casualties are acceptable — if not often deliberately targeted — casualties. After we kill Timothy McVeigh, Americans should think hard about what he was trying to tell us.

COPYRIGHT 2001 CREATORS SYNDICATE, INC.

May 14, 2001