"A Most Violent Year" — Hollywood On Mobbed-Up Immigrant Businesses

By Steve Sailer

02/02/2015

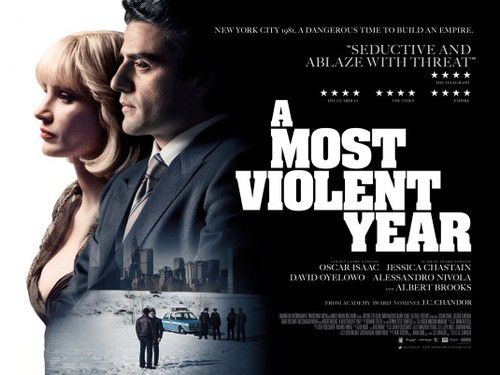

“A Most Violent Year” stars Oscar Isaac as, pretty much, a brooding Michael Corleone trying to go straight in the heating oil business in New York’s outer boroughs in 1981. Isaac plays a Colombian immigrant who has worked his way up to the point where he’s on the verge of buying a huge storage facility and dock, but his trucks are getting hijacked, the DA is looking through his records, and his bank is getting antsy about loaning him the money to complete his deal. His wife (Jessica Chastain) keeps suggesting her mobster father and brother could help him out with some muscle, but, as he repeatedly enunciates in his Guys-and-Dolls-like contraction-free English, he wants to play it clean: “I have always chosen the path that is most right.”

(Of course, he already made his million dollar downpayment on the property to its ultra-Orthodox owner in cash, so sticking to the straight and narrow in the heating oil business in NYC in 1981 is a relative concept.)

It’s the third movie from writer-director J.C. Chandor after his fine debut Wall Street movie Margin Call and his Robert Redford as an executive in a yachting accident in All Is Lost.

Chandor comes from a business background. The Kevin Spacey character in Margin Call is based on his father, a Merrill Lynch veteran. And before the director’s movie career finally took off, he did some real estate deals buying apartment buildings and then renovating them. Chandor’s point of view seems to be that affluent businessmen and corporate executives are people too.

On the plus side for A Most Violent Year, Isaac wears a terrific early 1980s camel hair overcoat. When I moved to Chicago in 1982, I wanted one, but always wound up buying a cheaper and easier to clean dark overcoat. As I’ve mentioned before, my sense of men’s fashion permanently congealed during the first Reagan Administration.

On the plus side for A Most Violent Year, Isaac wears a terrific early 1980s camel hair overcoat. When I moved to Chicago in 1982, I wanted one, but always wound up buying a cheaper and easier to clean dark overcoat. As I’ve mentioned before, my sense of men’s fashion permanently congealed during the first Reagan Administration.

Many movies these days are underexposed (e.g., American Sniper, Wild, Gone Girl). It seems to be a shortcut to getting your film described as “dark.” (Tarantino seems to be just about the last director who likes sunshine.)

This one is extremely underexposed.

This new film got good reviews, but none of the Oscar nominations it needed (instead the more crowd-pleasing “Whiplash” got the small movie Best Picture nod), and hasn’t taken off at the box office.

One problem is the stilted dialogue Chandor gives Isaac, who comes across as sententious. Chastain has one hilarious line at a key plot point, but otherwise doesn’t get as good lines as either Jennifer Lawrence or Amy Adams in the much funnier American Hustle, which is set in the a very similar era, location, and milieu.

A second problem might be that while Oscar Isaac, the son of a surgeon, has been a classy presence in movies for some years (e.g., as Carey Mulligan’s supposed gangbanger husband in Drive, as the folksinger in the Coen Brothers’ last movie, as Prince John in Robin Hood), he’s not yet quite a movie star. Originally, Javier Bardem, who is a star, was going to play this role, but dropped out because of disagreements with Chandor. At present Bardem is to Isaac as Cary Grant was to David Niven.

In this movie, Oscar Isaac’s businessman employs a Spanish-speaking immigrant truckdriver doppelganger played by Elyes Gabel, yet another extremely classy Hispanic actor (Gabel was born in the Westminster neighborhood of London, around the corner from the Queen).

Another camel hair coat

A third reason is the relative lack of violence in A Most Violent Year. Movies are typically set in Hobbesian worlds ruled by violence rather than law, but the outcome of Chandor’s story implies that Chandor is aware that, you know, the heating oil business isn’t completely Hobbesian. Noah Millman explains (with lots of spoilers) how the plot turns out less apocalyptically than is portended:

So again, I wonder: is this part of Chandor’s point? That these “high-stakes” business dealings only feel that way because of the atmospherics we surround them with? That, in reality, we’re generally talking about the difference between doing fine and doing fantastically well, between being the sole boss or having partners, between doing it “the most right way” or having to cut a few corners?I could ask more questions of this ilk. Over and over, this film felt to me that it was subverting the expectations we have of the genre and the period, but I couldn’t tell to what end. If Chandor really was trying to make an homage to the great New York movies of the 1970s, stories of crime and corruption and battles for supremacy over a feverish and perhaps-dying city, then “A Most Violent Year” is simply a failure. But if he was trying to say, “no, it wasn’t really like that; it was honestly more like this, with much lower stakes than the lighting, score and line delivery would suggest” — well, he got what he wanted. But I’m not sure how satisfying a successful result really is as a cinematic experience.

I would presume that something Chandor learned from doing real estate renovations is that a lot of things blue collar in New York are a little bit mobbed up. But, on the other hand, they’re not actually very lethal, just expensive.

For example, I was once on a flight from New York to Las Vegas sitting next to three couples who were straight out of Married to the Mob. They squabbled nonstop with each other but were very friendly to me. When I asked what business they were in, the guy said “Private sanitation.”

Leasing Andy Gumps to construction sites is one of those odd little industries that organized crime controls in certain cities. They’re not inherently high profit extra-legal businesses like drugs. They’re typically just businesses that nobody really wants to be in all that much. So if bookies foreclose on a bunch of private sanitation businesses because of, say, the owners ran up big gambling debts, it might be worth it to organized crime to exert enough pressure to cartelize the business. Cartels work better if participants can enforce agreements to keep prices up with violence, and inherently unattractive businesses like private sanitation are easier to defend from outsiders.

So, if you hire construction workers in NYC, like Chandor did, you have to pay a ridiculous amount for one of those port-a-potties because the mafia took over that little business a long time ago.

But, you pay the mobsters’ monopoly price and nobody gets actually murdered and then you pass this cost of doing business in New York on to your tenants.

So it’s not really as operatically epic as Michael Corleone having Fredo rubbed out. A Most Violent Year turns out to be a cross between The Godfather series and American Hustle, with The Godfather’s sense of humor and American Hustle’s high stakes.

By the way, what history is the movie based on? A Colombian immigrant in New York in 1981 probably would be less tempted by the dark side of the heating oil business than by the cocaine trade. So who was in the heating oil business and why?

I looked up the historical heating oil — organized crime ties in the Tri-State Area. According to the Handbook of Organized Crime in the United States, a 1993 indictment in New Jersey explained that the Soviet Jewish immigrant mob of Brighton Beach ran it to evade about $1 billion in taxes annually:

It exploits the fact that diesel fuel (which is taxable as motor fuel) and home heating oil (which is not taxed) are basically the same product. The tax in this instance acts as a market control that creates the opportunity to illegally market an otherwise legal commodity. The typical scam for the tax evader is to buy No. 2 fuel oil and sell it as diesel with some markup for taxes but without remitting those taxes to the state or federal government. Often this scam is accomplished by the creation of a convoluted paper trail that includes dummy companies that cease operating before authorities are even aware that a crime has been committed.… States like New York and New Jersey are particularly vulnerable to this kind of motor fuel tax evation because they have many refineries and fuel distributors. The various investigations of the scheme have disclosed that many of those involved are ex-Soviets — most now living in Brooklyn (Brighton Beach).

The ex-Soviets wouldn’t pay taxes to the U.S. government, but they did pay taxes to the Gambino Family for protection.

Here’s an interesting observation from a New Jersey government investigator named Harvey Borak on why so many ex-Sovs become mobsters over here:

“… many of them back in their home country had been involved in black market and white-collar crimes, like one has said to me on occasion this is a country club, we are a very, very open country, we are a very open society, and for people who were able to survive doing these type of things in their very closed and very closely monitored society, it’s kind of easy for them to do it.”… The issue of screening these emigres by INS seems to be an area where either there is no policy, the policy is ambiguous, or it is not enforced.