American Indian Sports Mascots And Team Names A Big Hit In England, Europe, And Even Scandinavia

By Allan Wall

09/17/2018

Activists who oppose American Indian sports mascots and team names have their work cut out for them, because they are also being used across the pond in Britain and Europe.

The New York Times had an article about it, entitled Tomahawk Chops and Native American Mascots: In Europe, Teams Don’t See a Problem, By Andrew Keh, New York Times, May 7, 2018.

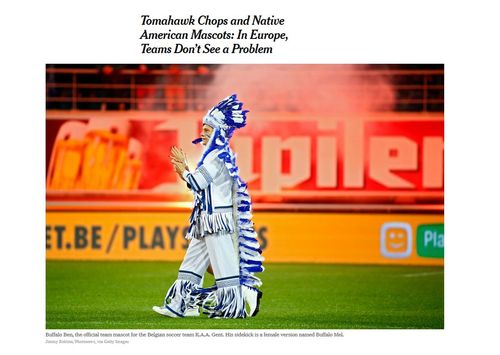

It starts out by introducing the reader to “Buffalo Ben”, a mascot for a Belgian soccer team:

Benjamin Bundervoet was wearing his normal workday outfit — a blue-and-white feathered headdress, a fringed tunic and chaps, bright paint streaked across his cheeks — as he stepped onto the grass. For the next few hours, Bundervoet would be Buffalo Ben, the official team mascot for K.A.A. Gent, a top Belgian soccer team. As the players warmed up before kickoff at a recent home match, Bundervoet smiled and waved a flag bearing the team’s logo, the profile of a Native American, which is also plastered around the Ghelamco Arena.

Interestingly, an Indian chief first appeared on a K.A.A. Gent flag in 1924, inspired by a visit to Ghent more than a century ago by Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show.

And Buffalo Ben is not the only one.

Scenes like this play out every weekend across Europe, where teams big and small and across a variety of sports employ Native American names, symbols and concepts of wildly variable authenticity in their branding. There’s the hockey team in the Czech Republic that performs a yearly sage-burning ritual on the ice, the rugby team in England whose fans wear headdresses and face paint, the German football team called the Redskins and many more.

Nobody saw a problem with this until recently.

For years, these teams were insulated from the vigorous discussion about the use of this type of imagery by sports teams in the United States, where critics long ago deemed the practice offensive and anachronistic. This year, the Cleveland Indians announced that they would stop using their Chief Wahoo logo on their uniforms beginning in 2019, continuing a decades-long trend in which thousands of such references have disappeared from the American sports landscape. During that same period, though, new examples were appearing in Europe, where teams and fans have long viewed the mascots and logos through kaleidoscopes of local culture and, detached from the charged history that the imagery carries in the North America, formed their own ideas about what is socially acceptable.

But these ideas are slowly being challenged, and increasingly these teams are finding themselves being asked to confront the same questions of representation, appropriation and stereotyping.

There’s a rugby team in England called the Exeter Chiefs, with their mascot Big Chief.

Exeter, which rebranded itself as the Chiefs in 1999, calls its team store the Trading Post and its online fan group the Tribe. Fans chat on a message board named Pow-Wow. Among the 15 bars at the team’s home stadium are Wigwam, Cheyenne, Apache, Mohawk, Tomahawk, Buffalo and Bison.

The article includes a link to the Exeter Chiefs’ fans chanting the tomahawk chop, used by the fans of the Florida State Seminoles and other teams. The FSU tomahawk chop has been called “the most intimidating tradition in college football”. Watch this video which shows Chief Osceola riding onto the field with a flaming spear, which he eventually thrusts into the turf. It’s impressive.

Back in Britain, the criticisms have begun for the Exeter Chiefs fans.

Two years ago, Rachel Herrmann, a historian of early American history at Cardiff University, wrote a blog post criticizing the team after noticing “a bunch of people dressed up as Indians” on a train platform one afternoon and learning that they were fans of the club.

There’s even a real Indian living in Exeter who has gotten involved in this.

“Americans, Canadians, they’re working on this issue, talking about it, debating,” said Stephanie Pratt, a cultural ambassador for the Crow Creek South Dakota Sioux and longtime resident of Exeter, England. “Europeans are late to the table. They’re just beginning to debate it — or maybe not at all.”

The Exeter Chiefs aren’t letting The New York Times drag them into the debate.

The Chiefs for the past two years have made no public statements about the discussion and declined several requests for comment from The New York Times. “We have ‘no comment’ to make and do not want to engage in any article on this subject,” a team spokesman wrote in an email message last week.

There’s a hockey team in the Czech Republic with an Indian mascot. Historically, there’s an important connection between American Indian culture and Bohemia, as that’s where many of the trade beads acquired by American Indians were made.

HC Plzen, a hockey team in Pilsen, Czech Republic, rebranded with an American Indian logo and mascot in 2009. The Czech Republic is one of the many countries in Europe where the novels of the 19th-century German writer Karl May, who wrote adventure stories about the American West that depicted Indians as noble savages, were wildly popular and hugely influential in shaping the European public consciousness of Native Americans. (May, whose books have sold more than 100 million copies, never set foot in North America.)

And there’s a U.S. WWII military connection.

Lucie Muzikova, a spokeswoman for HC Plzen, said the club’s logo — the profile of a Red Indian wearing a white headdress — was designed in part as a nod to the insignia of the United States Army’s Second Infantry Division [Pictured right] which liberated Pilsen near the end of World War II.

HC Plzen carries out some Indian-themed pre-game ceremonies.

As part of its in-game presentation, HC Plzen employs the help of West Park, a nearby museum with a 19th-century American West theme. At the start of each season, performers from West Park, who are not of American Indian descent, conduct a public sage-burning ceremony, traditionally seen as a cleansing ritual, inside the team’s arena. Before every game, the performers play drums and carry out a purifying ritual as the players skate onto the ice amid a swirl of smoke, lights and music.

“We perform everything the way the Natives are doing it and with deep respect,” Petra Michlova, a marketing manager and show team member at West Park, said.

In Sweden there is the Frolunda Indians hockey team in Gothenburg. Even Sweden’s Equality Ombudsman (“a government agency that addresses discrimination”) rejected complaints about this club from a concerned Swedish citizen.

According to Frolunda spokesman Peter Pettersson Kymmer, “…we sincerely think that our Indian, in our point of view, is in no way offensive to the Native Americans. On the contrary, it’s a tribute, and we’re proud to wear it.”

The NYT article only mentions one team on the other side of the pond which has dropped an Indian name, the Streatham Redskins, a hockey team in England, now called the Redhawks.

Apart from that one, as the article puts it “…most other clubs have no interest, at least for now, in doing the same.”