Automation: Silicon Valley Paper Provides Two Views of the Automated Future

02/13/2019

Sunday’s San Jose Mercury-News had a big spread on automation with photos and two articles. One is of the Don’t-Worry style — Robot-made coffee and burgers in SF? How automation is affecting jobs — produced by the SJM and appropriate to the tech-friendly view of the Silicon Valley town.

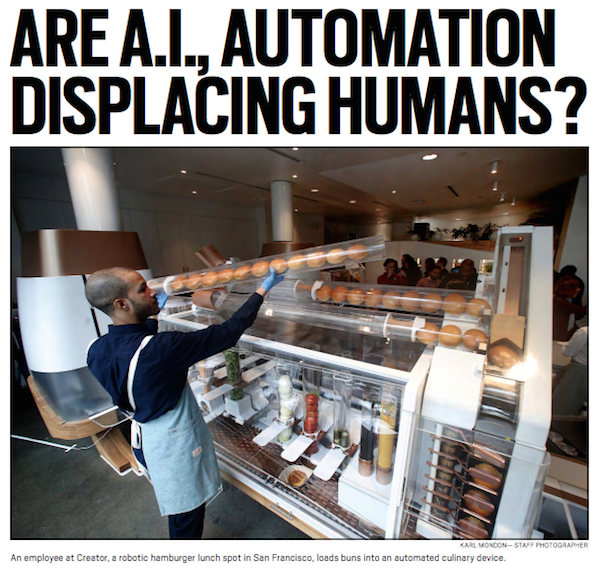

Below, a front page photo asks the big question of job displacement:

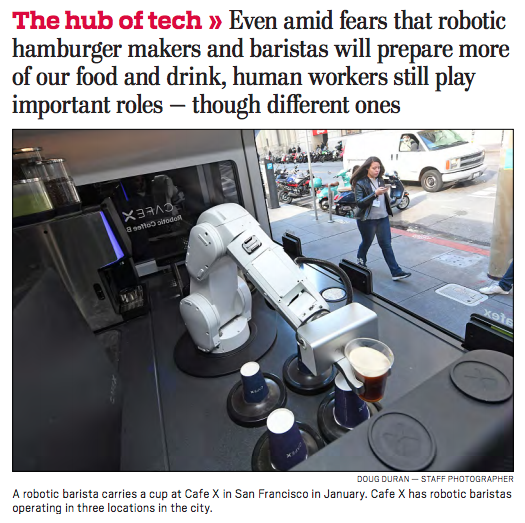

Below, another SJM photo shows a robot barista preparing coffee at Cafe X in San Francisco.

The other article is from The New York Times and it takes a more critical view of the brave new world that technology is creating. It looks realistically at the bifurcated workforce of the future, where a small techno-literate group is financially safe and the remaining millions of ordinary workers are left out to dry.

The article is filled with facts about historical trends arising from mechanization and bears careful reading. It notes how the 2018 Brookings study (Is Automation Labor-Displacing?) found the “over the last 40 years, jobs have fallen in every single industry that introduced technologies to enhance productivity.” So now “productivity” is a buzzword that may indicate potential job loss.

Certainly the workplace is about to change fundamentally, and low-skilled people like the thousands of Central American aliens claiming asylum will not be needed at any wage because the machines will soon be cheaper and more efficient. Indeed, the United States will not need any low-skilled immigrant workers, because:

Automation Makes Immigration Obsolete

The New York Times article is reprinted in another paper, linked below:

Tech is splitting the workforce in two, By Eduardo Porter, New York Times, February 10, 2019

PHOENIX — It’s hard to miss the dogged technological ambition pervading this sprawling desert metropolis.

There’s Intel’s $7 billion, 7-nanometer chip plant going up in Chandler. In Scottsdale, Axon, the maker of the Taser, is hungrily snatching talent from Silicon Valley as it embraces automation to keep up with growing demand. Startups in fields as varied as autonomous drones and blockchain are flocking to the area, drawn in large part by light regulation and tax incentives. Arizona State University is furiously churning out engineers.

And yet for all its success in drawing and nurturing firms on the technological frontier, Phoenix cannot escape the uncomfortable pattern taking shape across the U.S. economy: Despite all its shiny new high-tech businesses, the vast majority of new jobs are in workaday service industries, like health care, hospitality, retail and building services, where pay is mediocre.

The forecast of an America where robots do all the work while humans live off some yet-to-be-invented welfare program may be a Silicon Valley pipe dream. But automation is changing the nature of work, flushing workers without a college degree out of productive industries, like manufacturing and high-tech services, and into tasks with meager wages and no prospect for advancement.

Automation is splitting the U.S. labor force into two worlds. There is a small island of highly educated professionals making good wages at corporations like Intel or Boeing, which reap hundreds of thousands of dollars in profit per employee. That island sits in the middle of a sea of less educated workers who are stuck at businesses like hotels, restaurants and nursing homes that generate much smaller profits per employee and stay viable primarily by keeping wages low.

Even economists are reassessing their belief that technological progress lifts all boats, and are beginning to worry about the new configuration of work.

Recent research has concluded that robots are reducing the demand for workers and weighing down wages, which have been rising more slowly than the productivity of workers. Some economists have concluded that the use of robots explains the decline in the share of national income going into workers’ paychecks over the last three decades.

[ … ]

In 1900, agriculture employed 12 million Americans. By 2014, tractors, combines and other equipment had flushed 10 million people out of the sector. But as farm labor declined, the industrial economy added jobs even faster. What happened? As the new farm machines boosted food production and made produce cheaper, demand for agricultural products grew. And farmers used their higher incomes to purchase newfangled industrial goods.

The new industries were highly productive and also subject to furious technological advancement. Weavers lost their jobs to automated looms; secretaries lost their jobs to Microsoft Windows. But each new spin of the technological wheel, from plastic toys to televisions to computers, yielded higher incomes for workers and more sophisticated products and services for them to buy.

Something different is going on in our current technological revolution. In a new study, David Autor of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Anna Salomons of Utrecht University found that over the last 40 years, jobs have fallen in every single industry that introduced technologies to enhance productivity.

The only reason employment didn’t fall across the entire economy is that other industries, with less productivity growth, picked up the slack. “The challenge is not the quantity of jobs,” they wrote. “The challenge is the quality of jobs available to low- and medium-skill workers.”

Adair Turner, a senior fellow at the Institute for New Economic Thinking in London, argues that the economy today resembles what would have happened if farmers had spent their extra income from the use of tractors and combines on domestic servants. Productivity in domestic work does not grow quickly. As more and more workers were bumped out of agriculture into servitude, productivity growth across the economy would have stagnated.

“Until a few years ago, I didn’t think this was a very complicated subject: The Luddites were wrong, and the believers in technology and technological progress were right,” Lawrence Summers, a former Treasury secretary and presidential economic adviser, said in a lecture at the National Bureau of Economic Research five years ago. “I’m not so completely certain now.”