By Steve Sailer

12/17/2013

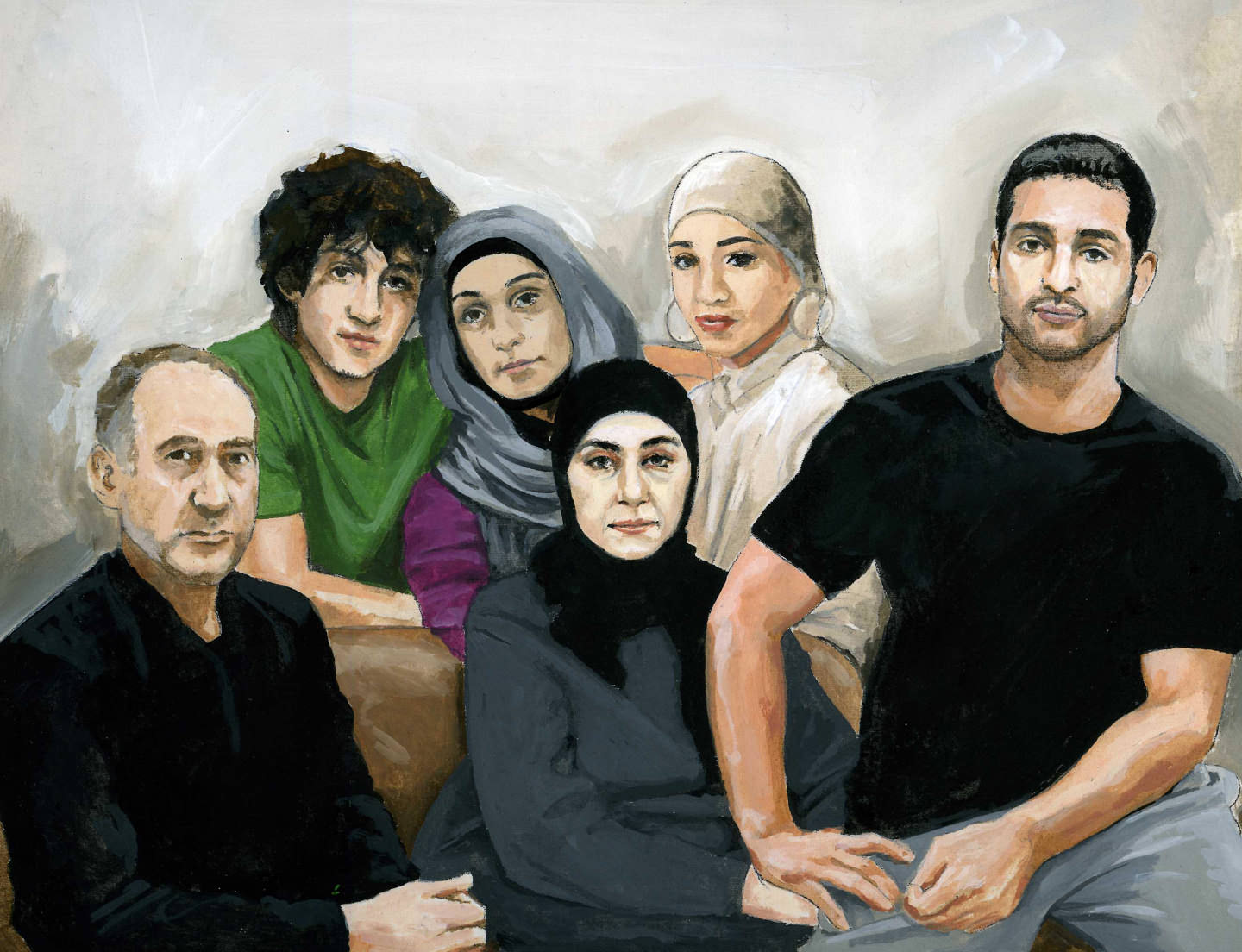

The Boston Globe has published an in-depth story of the Tsarnaev family, including asking a key policy question: Why were they here?

The Globe’s five-month investigation, with reporting in Russia, Kyrgyzstan, Canada, and the United States, also:

? Fundamentally recasts the conventional public understanding of the brothers, showing them to be much more nearly coequals in failure, in growing desperation, and in conspiracy.

? Establishes that the brothers were heirs to a pattern of violence and dysfunction running back several generations. Their father, Anzor, scarred by brutal assaults in Russia and later in Boston, often awoke screaming and tearful at night. Both parents sought psychiatric care shortly after arriving in the United States but apparently sought no help for Tamerlan even as his mental condition [hearing voices in his head] grew more obvious and worrisome.

? Casts doubt on the claim by Russian security officials that Tamerlan made contact with or was recruited by Islamist radicals during his visit to his family homeland.

? Raises questions about the Tsarnaevs’ claim that they came to this country as victims of persecution seeking asylum. More likely, they were on the run from elements of the Russian underworld whom Anzor had fallen afoul of. Or they were simply fleeing economic hardship.

In any case, the family from which two alleged bombers emerged very likely should not have been here at all. … .

[Anzor, the dad] would later say in interviews that he also earned a law degree, but the university in Kyrgyzstan’s capital, Bishkek, where his three sisters and one of his brothers earned law degrees, has no record that Anzor received a diploma. Friends say he was more likely just taking classes.

Anzor and family members have also said that he worked for a district prosecutor’s office in Bishkek, but the Kyrgyz Interior Ministry has no record that Anzor ever did. More likely, according to Uzbek Aliev, a leader of Tokmok’s Chechen diaspora, he had some kind of unpaid internship.

But the internship provided Anzor with something perhaps more valuable to him than a law degree — an ID card from the prosecutor’s office. This, according to friends, helped him ward off corrupt officials and extortion gangs seeking to get in on his main livelihood: “Shuttle trading,” moving consumer goods to meet free market demand in the ruins of the Communist economy.

One product Anzor traded in was tobacco, according to Badrudi Tsokaev, a longtime family friend. Anzor and an uncle would transport tobacco from a factory in southern Kyrgyzstan and to buyers elsewhere in the former Soviet Union. It was a good business, but a dangerous one. Gangsters were also drawn to the tobacco trade.

It is possible that threats from such criminals prompted Anzor’s hasty departure, with his family, from Kyrgyzstan. His wife would later suggest as much, but that wasn’t the story Anzor told.

In interviews with Russian journalists after the Boston bombing, Anzor said that the family had been the victims of oppression of ethnic Chechens. Anzor, according to family and friends in the United States, suffered post-traumatic stress disorder and often woke up screaming or weeping in the middle of the night.

But some associates believe that Anzor exaggerated his narrative of persecution. Among them is Aliev, the deputy head of the Chechen diaspora. While Chechens faced hardships in Kyrgyzstan, he said, “there was no special treatment, bad treatment, for Chechens” in Tokmok when Anzor lived there.

Some experts have also raised doubts about Anzor’s claim. Kathleen Collins, a University of Minnesota associate professor of political science who worked in Kyrgyzstan in the mid-1990s, said that Chechen community leaders complained about harassment in Kyrgyzstan after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks in the United States — and after the Tsarnaevs left Kyrgyzstan for Zubeidat’s homeland of Dagestan in southern Russia.

Taking a look at the life of Tamerlan and Dzhokar’s grandfather sheds light on their violent roots.

Mark Kramer, program director of Harvard University’s Project on Cold War Studies, who has testified in a number of asylum cases from the region, says he sees, “no basis for their being granted asylum at all.”

So, too, do associates of the family in Kyrgyzstan scoff at the notion of such persecution. As the family friend Tsokaev, put it, “He made that up … so that the Americans would give him a visa.”

Zubeidat told a different story of the origins of her husband’s nervous disorder and nightmares to a health care aide in the United States who worked with Zubeidat for over a year caring for a disabled couple in West Newton. The aide said Zubeidat told her that Anzor had “tried to prosecute” some members of the Russian mob involved in an illegal trading venture. “When the case was over, the mob came and took Anzor for one week and tortured him so severely that he almost died. When they were done they dumped him out of their truck in the middle of nowhere,” said the aide, who spoke on condition of anonymity.

“Zubeidat went to the hospital and when she saw how horribly beaten he was she said that she realized they had to get out of the country,” the associate said.

The mob, according to this account, took one macabre, parting shot. Before Anzor could leave the hospital, someone took the family’s German shepherd, cut off its head, and deposited it on the Tsarnaevs’ doorstep.

“Zubeidat said that is why they left,” added the aide.

Back in Kyrgyzstan, there is still another account of why the Tsarnaevs wanted to go to America, and it, too, has nothing to do with persecution.

“We watched all these films, saw how beautiful Hollywood was,” said Nurmenov. “It seemed that life was good there. [Anzor] told me, ‘Let’s go to America. Why should we sit here and rust?’ One day I found out that he was going away. He said, ‘You can get a visa to America. It’s easy.’ And then later he left.”

We need a National Immigration Safety Board that inspects policies and implementation after disasters like this, much like the National Transportation Safety Board uses plane crashes to order improvements in procedures.

By the way, there’s little mention of the role of Uncle Ruslan, who used to be married to CIA insider Graham Fuller’s daughter. I've always thought it likely that that somehow played a role in the Tsarnaevs' getting refugee status, but it never comes up in this article.

Also, the reporters didn’t come up with anything new on the ritual murder on the tenth anniversary of 9/11 of three of Tamerlan’s dope-dealer buddies, or the FBI shooting of a Chechen "refugee" while being questioned about the triple murder.