Breaking Into Your Own House

By Steve Sailer

07/30/2009

Throughout StupidGate, whenever anybody rhetorically says, "Officer Crowley should have left as soon as Professor Gates showed ID demonstrating he'd broken into his own house!" I've had in the back of my mind a vague recollection that I've heard something somewhere about a man who broke into his old house after his wife had changed the locks on him.

Therefore, a cop shouldn’t just leave, especially when the angry, agitated man is acting much like a man whose wife has changed the locks. And, when the man won’t answer the cop’s question about who else is in the house, the cop has to hang around while Dispatch checks the name of the householder he called in for restraining orders, warrants, and the like. (Maybe they should have thicker skins, but cops really don’t like it when you loudly hurl abuse at them while they're on the radio checking on these matters.)

I couldn’t remember the story, so I kept coming up with thought experiments scenarios in which a rich Texas oilman breaks into his old house in order to hurt his future ex-wife.

But then it finally occurred to me that this isn’t just a thought experiment. In fact, it was not only one of the most notorious crime stories of my lifetime, but, heck, I even worked for the man’s legendary Houston defense attorney Racehorse Haynes in 1980 as a research assistant, pulling together his scrapbook on this case for use in an autobiographical book Racehorse planned to write with Rice sociologist William Martin.

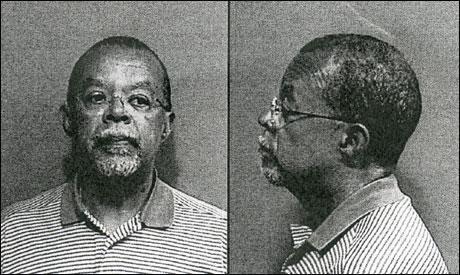

It’s the story of oil heir T. Cullen Davis, who may still be the richest man ever tried for murder in the United States. In 1976, he broke into his former $6 million dollar mansion and settled down to wait for his separated wife and her new boyfriend to get home.

When his young stepdaughter surprised him, he took her to the wine cellar and executed her. He then waited for his primary targets. When the couple walked in, Davis shot both, killing the man but only wounding his tough, gold-digging wife.

Two young people who were friends of the family walked up the driveway of the 180 acre estate. Davis shot one, and the girl ran off and flagged down a passerby. The wounded wife crawled off down the hill on the other side. Both witnesses immediately and separately told neighbors, "Cullen’s up there shooting everybody."

Racehorse Haynes got Cullen Davis acquitted.

A few years later, Davis was back in jail for paying a hitman $25k to kill the judge in his divorce settlement case. The man went to the FBI, who got the judge to climb in the trunk of a car, covered him with ketchup, and took a Polaroid. They then wired the supposed hitman for sound and filmed him on video as he showed Davis the picture of the supposedly murdered judge and accepted the cash in return.

Racehorse got him off again.

I lost track of Cullen Davis after that, although I do recall one year the Forbes 400 issue did a Where Are They Now? feature on former members. Davis was now recognized as America’s Poorest Man based on having the most negative net worth of anybody in America. The funny thing is, though, that when you are worth $-800 million, you still live pretty well.

Racehorse is doing fine in his early 80s. He told the ABA Journal:

For instance, he’s represented three dozen women in what he refers to as “Smith & Wesson divorces,” which are cases where the husband had been abusive, leading the wife to kill in self-defense. “I won all but two of those cases,” he says. “And I would have won them if my clients hadn’t kept reloading their gun and firing.”

I remember some of those very Texan cases from my job summarizing Mrs. Haynes' scrapbook of his newspaper coverage: like Sicilian grand opera set to the twang of steel guitars.

After a meeting at Racehorse’s house in Houston in 1979, he insisted on driving me back to my car, which was only parked a block way. That’s because he had just bought a whale-tail Turbo Porsche. He floored it and we accelerated down his quiet street (in River Oaks?) for three blocks, topping out at 85, then, like a rocketship in a Robert Heinlein novel, decelerated for three blocks back to zero. I pointed to some random car, got out, thanked him, then, after he had turned the corner, walked the five blocks back to my Datsun 310.

Sen. Fred Thompson played Racehorse in a 1992 miniseries "Bed of Lies" about a doctor client of his who was accused of poisoning his wife, the daughter of a very rich, very angry man. Racehorse got the doc off, but a hit man rubbed him out later. Haynes and Thompson are equally charming, but Haynes is a high-energy bantamweight, while Thompson, as we saw in the Presidential primaries last year, is not.

Dennis Franz of NYPD Blue played Racehorse in a 1995 miniseries about Cullen Davis, aptly entitled "Texas Justice." Once again, curious casting.