03/15/2015

How is an economy supposed to function when human workers are becoming obsolete because of smart machines in the workplace? Leisure time is certainly nice, but humans require money for acquiring goods and services. Curiously, the captains of industry don’t seem to notice the consumption part of the economy equation, and when people don’t get paychecks they are not shopping.A 2013 Oxford University study (“The Future of Employment”) asserted that nearly half of American jobs may be automated in 20 years, so the Jetsons future is rushing toward us. The jobless recovery suggests that big automation is already here to a degree, and its negative effects upon employment will only grow.

In a 2014 PBS Newshour report (below), co-author of “The Second Machine Age” Andrew McAfee imagined a future society like ancient Greece, where “citizens debated democracy and led enlightened lives; they were supported by the work of human slaves … we won’t have human slaves, we’ll have an army of technologies that are doing the heavy lifting required for a society.”

Robot utopia — woo hoo!

When enlightened Athenians weren’t debating democracy, they were also sentencing Socrates to death for his unpopular opinions, so the cultivated lifestyle experienced a few bumps along the way.

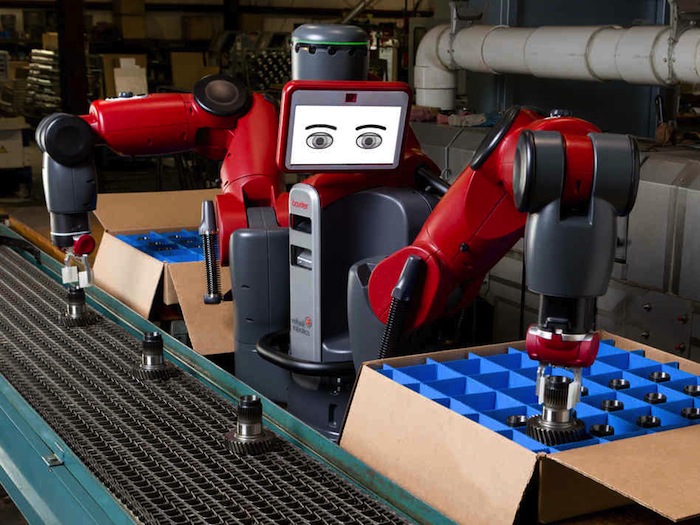

In addition, roboticist Rodney Brooks explained how the Baxter robot (pictured) does unpleasant tasks that no human in the factory wants to do. He perhaps does not understand that people don’t flock to factories to do fun things, but to perform jobs to get a paycheck.

What kind of society would evolve where leisure would be the norm rather than work? These days, when we meet someone new we ask, “What do you do?” Perhaps in the future that question will be, “What’s your hobby?”

The world is an interesting place: some people would be very happy filling a life with intellectual or artistic pursuits. But probably not everyone.

Anyway, the future robotic utopia imagined by McAfee has a lot of troubling details to be ironed out.

For one thing, importing millions of immigrant workers for non-existent future jobs is a very bad idea. Today’s unemployed persons are angry, and they have a right to be after the government allowed the shipment of whole industries overseas and imported foreign workers by the millions to take the remaining jobs. Now workers face smart machines who don’t need sleep, lunch breaks or paychecks. (See my article “Three Stakes in the Heart of the American Dream.”)

Jeb Bush recently visited New Hampshire and while there endorsed the Senate’s failed Gang of Eight amnesty bill which included the doubling of legal immigration. Unfortunately he is typical among politicians in ignoring the effect of automation on the nation’s requirement for future workers. America needs Zero imported workers.

Robots may make it harder for some Americans to get ahead, CNBC, by Heesun Wee, March 13, 2015More linebacker than running back, Baxter is a tough, reliable worker. His arm span is wide and he takes instruction well, all valuable assets on a manufacturing shop floor.

Baxter is a robot and made by Rethink Robotics, a start-up founded by Rodney Brooks, who produced the Roomba vacuum when he was at iRobot in the 2000s. Robots and more broadly automation have been around for decades, especially in the auto industry. We’re talking six-figure robots in cages that are so big they could hurt workers if the machines toppled onto humans.

Robots have since advanced and are smaller, nimble and more affordable. Small- to medium-sized businesses are introducing automation onto shop floors. Some economists see a future where robots will push down labor costs and lift productivity so companies will think twice before offshoring U.S. jobs.

Automation is forecast to raise productivity by as much as 30 percent in many industries, and cut labor costs by at least 18 percent in the coming decade, according to recent research from The Boston Consulting Group. As an example, “We’re thinking about something like a 16 percent drop in the labor costs for manufacturing plants over this time period,” Hal Sirkin, a senior partner at The Boston Consulting Group, told CNBC. The researchers did not spell out how labor cost savings might translate into potential number of jobs lost to automation.

This is the embedded “botsourcing” fear. More robots = lost jobs. Or seen another way, higher wage pressures = more automation. And maybe even more worrisome is a suspicion that robots will not only jeopardize jobs but make it even harder for less-skilled workers to remain employed, let alone get ahead.

From 1995 to 2013, technological changes accelerated America’s output per worker. But those gains were offset by income inequality and a drop in labor force participation. Those working or looking for work have declined to around 62.8 percent from prerecession levels of around 66 percent, suggesting more Americans are getting discouraged and disappearing permanently from the workforce. President Barack Obama laid out how middle-class stagnation is dragging down the economy in the 2015 Economic Report of the President released by the White House last month.

So if advanced robots knock out more automatable jobs, will lower-skilled workers fall further from the pack and essentially vanish from the American jobs landscape? This is a big debate among economists and experts on robotics.

The recovery after the Great Recession has been dominated by job gains in lower-wage industries, according to analysis from the National Employment Law Project. Higher-wage sectors have accounted for 33 percent of new jobs, while mid-wage industries pulled in 26 percent of new positions from July 2013 to July 2014. But lower-wage sectors have ricocheted higher during the same period, raking in 41 percent of new jobs.

“Economic growth has been more and more concentrated not just at the top, but at the tippy top of the pay scale,” said economist Jared Bernstein, a senior fellow at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities in Washington, D.C.

As more automation seeps into industry and everyday consumer lives, there’s a concern robotic innovation may sideline more Americans — workers already buckling under low employment levels and stagnant wages.

A robot in every home

It’s been eight years since Bill Gates predicted a robot in every home. “I can envision a future in which robotic devices will become a nearly ubiquitous part of our day-to-day lives,” wrote Gates in the January 2007 edition of the Scientific American.

States are passing laws on driverless cars. Amazon is developing small, unmanned aerial vehicles, known as drones, to deliver packages to customers’ homes. The U.S. military is researching robots for search and rescue operations. And there are surgical robots to treat soldiers in remote regions. U.S. venture capital investments in robotic start-ups nearly tripled to $172 million in 2013 from 2011 levels. That’s according to PwC’s MoneyTree survey, which tracks VC investments.

But the promise of new machines — and its presumed preference for higher-skilled workers — also highlights how innovation can weed out some workers. About 47 percent of U.S. employees — nearly half — are in jobs that could be at risk of being displaced by computerized technology, according to a 2013 University of Oxford study.

Measured another way, the portion of automatable tasks done by robots globally is projected to reach nearly 25 percent in 10 years, up from 10 percent at current levels, according to the International Federation of Robotics and The Boston Consulting Group. In China, for example, where wages are rising, the nation ordered more robots in 2013 than any other country, some 37,000, according to research published last year from PwC and the Manufacturing Institute.

Other economic data show the emerging gulf between pockets of workers, as U.S. employment levels are historically low and productivity keeps rising.

Bernstein at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities has tracked how labor productivity and private employment became decoupled in the late 1990s. The U.S. employment-to-population ratio is lower than any time in at least 20 years.

The gap between productivity and employment can partly be explained by weak labor demand. The U.S. job market had been slack but recently has tightened. The unemployment rate dropped to 5.5 percent in February, according to the Labor Department.

“It’s not just automation that leads to that gap. It can also be weak labor demand,” Bernstein said.

Of course, companies aren’t just deploying robots to slash human-powered jobs. The math behind automation isn’t that simple. Next generation robots will require college-educated electrical and mechanical engineers and higher wages.

And despite robotic advances, some tasks still need that nuanced human touch and decision-making that can’t be replicated, so far, by machines.

Consider the gestures of a health-care worker helping an aging patient. “There are actually lots of low- and middle-wage occupations that are hard to replace by labor-saving technology,” said Bernstein. “I don’t think robots have sealed our fate as much as people think they have,” he said.

Meet Baxter

Rethink Robotics, based in Boston, makes Baxter, which sells for about $25,000 or a fraction of what robots cost a generation ago. And while older robots operated inside cages, Baxter and newer robots operate freely, right on shop floors next to humans. Baxter has arms and a computer screen that renders facial expressions — telegraphing to co-workers their next moves.

Factory workers can also guide Baxter’s arms through physical tasks on an assembly line — in essence programming Baxter through demonstrations, and cutting the need for specialized software or technicians. Reprogramming older machines for automated tasks used to be expensive. A lot of shops have graveyards of dusty, boxy robots that simply became too costly to reprogram and repurpose.

Back then, “you had to create the programming to do the jobs,” said Jim Lawton of Rethink Robotics. “It was like buying an iPhone with no apps.”

Looking ahead, four sectors in particular are forecast to employ roughly 75 percent of robots through 2025 — the transportation, machinery, computer and electrical fields, according to the Boston consultancy’s report, released last month.

And robots over human labor already makes economic sense. Robotic price and performance are better than — or near parity — with manual labor costs in the U.S. auto and electrical equipment industries, according to the consultancy’s research. In other areas like the U.S. furniture industry, robots could surpass manual labor in the next decade.

Beyond labor cost savings, some companies are using automation to expand and improve product quality and increase production. The ‘bots are not only here, they’re multiplying.

Justin Rose is a manufacturing expert for The Boston Consulting Group. He studies trends like how robotics and other economic shifts are contributing to American re-shoring. Years ago, Rose first encountered Baxter, roaming free on a shop floor and without a cage.

“For the price of a car, you can have a robot that can run 24 hours a day with impressive capabilities,” Rose said. “This is the beginning of that revolution.”

This is a content archive of VDARE.com, which Letitia James forced off of the Internet using lawfare.