By Steve Sailer

09/14/2018

Do conspiracy theorists ever get anything right? If they don’t, does that prove that conspiracies never happen?

One way to examine these questions is to consider a giant conspiracy that actually happened: by the end of WWII, about 9,000 people were working on Ultra — the deciphering of German Enigma machine codes — at Bletchley Park in the middle of England, on the route between Oxford and Cambridge.

Yet, Ultra remained an official secret in Britain for about a third of a century — only in 1974 did the floodgates open.

Today, Ultra is one of the more famous parts of the British war effort. Yet, it remained remarkably obscure for 29 years after the war ended. This history tends to undermine the often used anti-conspiracy talking point that no effort involving large numbers of people could stay secret for long.

Yet, many thousands of people moved to Bletchley to work at a vast decryption factory. The male workers tended to come from the nation’s intellectual elite (e.g., codebreaker Dilly Knox was one of four famous brothers) and the female workers from the nation’s social elite. So it’s not as if those 9,000 workers were remote, inarticulate obscurities. And yet, the public as a whole didn’t know anything about this vast enterprise until 1974.

Historian David Irving stumbled upon the Enigma secret in the 1960s, but kept this huge scoop out of his books even though the government couldn’t prosecute him for violating the Official Secrets Act without letting slip that there was a Secret. In return for playing ball, he was later given a copy of a secret document about Rommel.

So, here’s a question: did conspiracy theorists ever theorize about Ultra before 1974?

If not, why not?

Update: I poked around to see if anybody had discussed Ultra in the context of conspiracy theorizing and found a 2009 post on DailyKos from somebody named NCrissieB who has some sensible things to say about Bletchley as a conspiracy:

Conspirators of commonality need to control events, so these conspiracies tend to be either very small — a few people working to cause an isolated event such as a bank robbery — or very big indeed. Once you get past things that three or four people can do, perhaps with assistance from a handful of others, the complexity quickly escalates to a point that you need a lot of people. The more people you need, the more compelling the shared interest must be to motivate both their participation and their silence. So you rarely see medium-sized conspiracies of commonality. They’re either very small and acting on a mundane interest, or very big and acting on a compelling interest. … A big conspiracy also often has enough clout to conceal documents and/or plausibly spread disinformation.

The author goes on to suggest a theory that I came around to believing in the early 2000s as well:

These ‘open’ conspiracies can rarely act in complete secrecy, or at least not for very long. They’re known and often prominent actors, so their actions usually get at least some attention. Some of their actions are impossible to hide by the nature of the action itself. For example, you can’t test a new military jet in an underground hangar. So while these ‘open’ conspiracies do employ secrecy, they often also use something even more dangerous: disinformation. …

And often the conspirator need only kick-start the disinformation, then stand back and let the public continue it. The UFO controversy is a case in point. There is now good evidence that some in our government thought attributing unusual aerial events to extra-terrestrials would be a good way to keep new technologies secret. The early ‘leaks’ that aliens might be visiting earth sparked a spate of science fiction movies, but also a plethora of concerned citizen groups determined to discover the truth. The government then issued official denials, and seeded ‘skeptic’ groups to debunk claims of UFOs, including some “explanations” as transparently absurd as the claims themselves.

Once both ‘believers’ and ‘skeptics’ had reached critical mass, those who had begun the disinformation campaign could sit back and watch as unprovable claims were met by often equally unprovable denials, all of it deflecting attention from the legitimate question: “What flew over my house last night?” The real answer — when it wasn’t an ordinary event — was probably a classified military project. But so long as the witnesses and skeptics were arguing about little grey visitors from Zeta Reticuli, the military could test almost anything, almost anywhere, and no one would be the wiser.

This strikes me as plausible, and I’ve made this argument myself several times. But I have to confess that I don’t have much smoking gun evidence that anybody in the U.S. government ever actually stoked UFO rumors as a distraction from military testing.

The late Jerry Pournelle told me the KGB did this to cover up a Soviet semi-orbital weapon that came down spectacularly over Latin America: have local Communists call up newspapers and rant about flying saucers and little green men to confuse and discredit the accurate eyewitnesses. Of course, maybe Jerry was projecting?

Elements within the U.S. government sometimes used sci-fi authors at times for various purposes, much as the British government used detective fiction authors to outsmart the Germans in WWII cloak and dagger episodes.

For example, in 1945-47, Robert Heinlein got help from the US Navy in learning about rockets, such as being invited to see the test launch of a captured German V2 missile in New Mexico, which he used in his classic juvenile novels from Rocket Ship Galileo onward. What the Navy wanted from Heinlein was for him to portray space travel as something that naturally should be under the control of the Navy — e.g., space ships, Space Marines, etc. But this wasn’t exactly a vast top-down conspiracy either: it was one Navy pal of Heinlein’s who was a player in the Pentagon.

In terms of hiding classified technology that can only be tested out in plain sight, it was a great success. But that success comes at a steep price: an entirely justified distrust of government and our media. Every time our government spreads disinformation and the media obligingly repeat it — as happened in the run-up to the Iraq War — the distrust only deepens. It becomes ever more difficult to know what sources to trust and what claims to believe, and more difficult to make informed decisions as citizens in a democracy.

Commenter Last Real Calvinist writes:

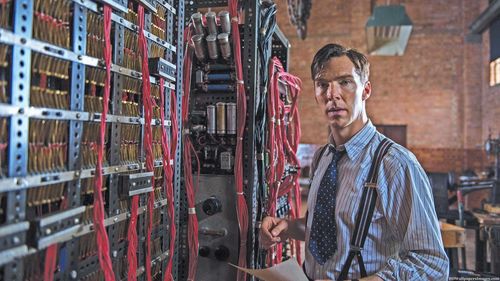

I’ve watched a number of TV shows and movies in the past few years that have featured Ultra/Bletchley, e.g. The Bletchley Circle, The Imitation Game, etc. A theme common to all of them was the absolute need for total secrecy. No one could talk about the Ultra ‘conspiracy’ at all, full stop, the end.

But if there were 9K people involved with Ultra in one way or another, did they all really keep it secret, not just during the war, but thereafter?

And, assuming some of them did not, especially after the war (human nature being what it is), how many leakers can a conspiracy of that size tolerate before course of The Narrative is altered? If just one person starting talking about this super-secret code-breaking project that went on for years, who (other than those involved) would believe him? What if 10 started talking? 100? 1000? It seems Ultra really did remain pretty much a secret. How many people talked about it, and were disbelieved/brushed off?

While researching his 1964 book Mare’s Nest about the V-1 and V-2 programs, David Irving found out about Ultra. From Wikipedia:

Irving nonetheless worked the secret material into his book, writing an entire chapter about Enigma in the first draft of The Mare’s Nest. When it came to the attention of the authorities, “one night I was visited at my flat by men in belted raincoats who came and physically seized the chapter. I was summoned to the Cabinet Office, twelve men sitting around a polished table, where it was explained to me why [the information] was not being released and we appeal to you as an English gentleman not to release [it].” Irving cooperated and withdrew the chapter, but by this time he had copied enough material from Cherwell’s archive to furnish several more books.[2] ULTRA remained secret for another decade.

Back to Last Real Calvinist:

Another way of putting this: there have been waves of conspiracy theories about the JFK assassination (BTW, I don’t want to talk about any of these — please! — I just want to point out their existence). Yet the Warren Report Narrative, I would argue, still largely holds. The great beast that is The Narrative has been able to absorb the countless nips and stings of the conspiracy theorists, and on it lumbers.

This question is extremely pertinent in the context of current political campaigns, ‘fake news’, etc. When The Narrative assures us that, for example, Barack Obama’s presidency was the most ‘scandal-free’ in history, how many ‘conspiracy theorists’ — with their blogs, their alternative news sites, their tweets — does it take to wound and even bring down that narrative beast?

From 1978 to 1999, there was a law mandating a Special Prosecutor to persecute the Executive Branch so there were lots and lots of easily reported scandals. But then everybody in DC got sick of this and let the law expire, so there haven’t been many Executive Branch scandals until, voila, Mueller got appointed as Special Prosecutor of this that and just about anything.

As I’ve said over and over, reporters love government reports. The only reason anybody ever paid attention to the plague of Pakistani pimps in England, for example, is because the city of Rotherham commissioned an official government report. Disreputables like me had been writing about these scandals before the official government report came out, but when the official government report came out in 2014, it became a Thing in the news, at least in Rotherham.

So there were no Special Prosecutors during Obama’s terms and therefore there were No Scandals.

Now you might think that Black Chicago Democrat ~ Scandal, but that’s because you are not a good person. You might think that Valerie Jarrett, slumlord in chief of Chicago, might have some scandals about her. You might think that the fact that Obama’s first two chiefs of staff were Rahm Emanuel and William Daley might suggest something. But nobody wanted to hear about it. You might think that Tony Rezko had kind of a colorful past: he had been the Black Muslims’ business manager including managing their most famous convert Muhammad Ali. But you are wrong: there’s nothing more boring in this world than a man at the intersection of Muhammad Ali, the Nation of Islam, and the President of the United States.

Boring, boring, boring.

In other words, what’s the critical mass needed for a story (whether it’s the truth, or a conspiracy theory, or the exposing of a conspiracy, or whatever) to break through The Narrative’s powerful defenses, and enter the popular consciousness?

There is a lot of Information out there, and what people notice depends a lot upon the zeitgeist.

For example, Bletchley Park is vastly famous today in part because the great Alan Turing, a major contributor to modern information technology, was gay and died tragically after being legally punished for his taste for young rough trade (it’s never phrased in those terms). And he fought Nazis.

In contrast, the great American who is a near exact counterpart in terms of his contribution to information technology, Claude Shannon, is highly obscure.

Shannon, as 21-year-old at MIT in 1937, had just about the greatest idea anybody ever had. He was working on Vannevar Bush’s mechanical computer when he pointed out in his M.S. thesis that the problem with computing engines (going back to Babbage) is that each one was designed as tour de force of cleverness and originality. Babbage had been stumped, in part, by the cost of manufacturing gears with ten teeth to work with the decimal system.

Yet, there was an already existing body of thought going back to George Boole’s binary logic in the mid-19th Century that could be applied en masse to electrical engineering to make computing vastly more straightforward. Everything should be binary because we can compute anything we want to do with Boolean logic. This enabled Moore’s Law, which has been the biggest single driver of prosperity for decades.

And then Shannon came back a decade later by inventing Information Theory.

Now, I’m not going to get into trying to adjudicate a Turing vs. Shannon contest. They are both way above my level. They both deserve to be heroes. But each age gets not the hero-worship it needs, but the hero-worship it wants, and our age wants Turing hero-worship.