Cost to Educate Dumped Alien Kids Is Toted Up for Maryland

08/29/2014

Fox News took some basic facts from a Baltimore Sun news story and plugged in the dollars: 2804 illegal alien kids from Central America, at $13,609 per Maryland student comes out to $38,159,636. But that’s the cost for normal citizen students: the newbies also need Spanish-speaking teachers, special counselors and psychological treatment for trauma incurred on their trip.

If state taxes are not raised to pay the additional costs, then cuts will have to be made in other areas, likely in services to American students.

The Baltimore Sun account only included dollar amounts when they illustrated the sob story of what little Leonardo had to pay to reach the freebies of America.

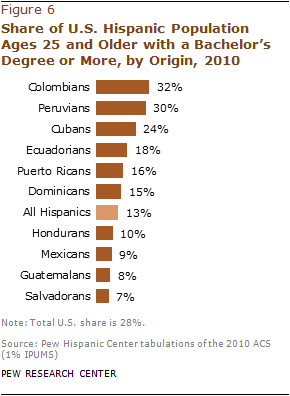

In addition, the cultures of Central America are among the least accomplished in educational achievement as shown by the Pew Research chart. Taxpayers will be forced to pay a lot of money for illegal alien services and many of the kids will probably drop out. Some of the kiddies don’t even speak Spanish or may not attended school at all in their homelands. They are exactly the wrong sort of foreigner for America’s future workforce which will require more education, not less.

Maryland schools see influx of immigrants from Central America: Children present challenges such as learning deficits, language barriers, Baltimore Sun, August 24, 2014With just $40 in his pocket and the killing of two friends fresh in his mind, 13-year-old Leonardo Enrique Navas set off from El Salvador in July and traveled alone for 15 days on buses and taxis until he crossed the border into Texas.

Every few days, he said, he called his mother in Maryland.

That was the first part of his American journey. When school opens Tuesday, he will have his first day in a U.S. seventh-grade classroom, at Bates Middle School in Annapolis, after being reunited with a mother he had not seen for seven years.

The thin, quiet boy will enter his classes not speaking English and with skills that may not be as advanced as those of his native-born classmates — posing challenges to educators that are being felt across Maryland.

While Maryland schools are well equipped to take in immigrants, the thousands of unaccompanied minors streaming across the border from Central America bring a new set of issues. They are most likely teenagers who not only don’t speak English but also have significant deficits in their education. School officials said they have seen nearly illiterate high-schoolers, girls who have been sexually assaulted during their journey across the border, and others who are overwhelmed and depressed.

“Many are coming with psychological or emotional trauma. Many are not literate in Spanish … and may only have gone to school up to the first or second grade. They may have huge gaps,” said Kelly Reider, coordinator for English language acquisition and international student services in Anne Arundel County.

In response, Baltimore-area schools are hiring more teachers who specialize in working with teaching foreign students, finding nonprofit partners to assist students when school resources are inadequate, and providing health clinics and group counseling sessions.

Maryland has taken in 2,804 unaccompanied immigrant children from January to July 30, the most per capita of any state, as their cases make their way through a backlogged immigration court, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. More children are expected to arrive throughout the year, with estimates from the state rising as high as 2,000 to 3,000.

Many of the students appear to have ended up in counties in Central Maryland, including Montgomery, Anne Arundel and Prince George’s, but Howard and Baltimore counties and Baltimore City have gotten a few dozen each as well.

Anne Arundel registered 1,000 new international students in about the past year, 600 of whom are kindergartners. Another 274 students had come recently from Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador, up from 162 the year before.

“It is a very different workload than it was two years ago,” said Reider, adding that her office had registered many more students this year.

The impact has been felt in Anne Arundel, where the county schools asked for 20 more teachers who teach English as a second language to handle the influx of international students; the county funded seven. There is now one teacher for every 30 international students in the county’s high schools and one teacher for every 40 elementary students, but Reider said she expects those ratios will rise as more students arrive throughout the year.

Montgomery County public schools have taken in 985 students from the region in the past year, 107 of whom are without a parent or relative in the country. As they register the children, school officials in Montgomery try to ensure that the students are healthy and have access to a health clinic, said Dana Tofig, a school system spokesman. Montgomery County, like other school systems, is not equipped to handle intensive counseling, and Tofig said the system is turning to nonprofits for help in meeting those needs.

“Some of these students may be facing issues that might be beyond what we can handle,” he said. “We are going to provide the services that kids need. Having more students who come needing more services, that does have a financial impact.”

Prince George’s has been registering 65 foreign students a day, most of them from Central America. Students coming to Prince George’s schools will receive a range of services, including placement in a group counseling session for international students.

Under a landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision in 1982, public school systems are required to provide children with an education regardless of their immigrant status. School officials say policies prohibit schools from asking about a child’s status when their parents or guardians register them.

While the state has taken in many new immigrants from Central America, enrollment figures show that those foreign-born students account for less than half of the total enrollment increases the state has seen in recent years. Schools absorbed 6,500 new students the year before the state saw a flood of new unaccompanied youths to the U.S.

Leonardo spent part of last year attending sixth grade, his mother, Marleni Araceli Navas, who also does not speak English, said through an interpreter. She first came to the U.S. in 2003 to make a better future for her son, who stayed behind with her parents. She stayed three years and then returned to El Salvador to try to work.

“As hard as you work there, you can’t make it work,” she said.

So she came back to the U.S., married and had three more children. The youngest is still in her arms. She spoke to Leonardo every few days by phone, but as he grew older she began to worry for his safety.

“When you are 10 or 11, [the gangs] come to you and if you don’t work for them, they kill you,” she said.

Four years ago, she added, her brother disappeared. She doesn’t know whether he is dead or alive.

Leonardo had seen the gangs recruiting people at the school near their house and, two days before he left, two children he knew were killed, she said.

While she was afraid for him to make the trip alone, she said her greater fear was what would happen if she left him there.

Leonardo traveled for days on a crowded bus, suffering from carsickness. But, he said, he wasn’t afraid because he was making progress.

Once he got to the Mexican border, his family made a partial payment on a $3,500 fee to have someone take him into Texas. He was apprehended by federal immigration officials and eventually took a flight to Baltimore, where he was reunited with his mother. His mother said he will have to appear at an immigration court to ask to stay in the country.

As he awaited the opening of school, he said he is nervous about feeling like a foreigner but wants to make new friends.

“We are hearing some amazing stories,” said Patricia Chiancone, an outreach counselor in Prince George’s International Student Counseling Office. The number of students from Central American countries rose there from 65 to 180 in two years. Over the past year, Chiancone said, the number of unaccompanied minors who have enrolled has doubled. The school system increased staff to register new students and added evening hours.

“We are talking about hundreds of kids a week, and there are several counselors doing the registration,” she said.

The students will enter a well-established course of study that segregates them from the rest of students for a large portion of the school day until they are proficient in English. The program, which has existed in schools for decades, is known as English for Speakers of Other Languages, or ESOL. Many school systems designate a few schools to become magnets for English-language learners, so all the international students are bused to a few schools.

“We have had immigrant students for a very long time and have streamlined the system,” Chiancone said.

The academic classes are taught by educators with a specialty in teaching subjects to non-native speakers, and a single class may be filled with students from around the globe who speak languages from Urdu to Russian to Spanish. Students attend regular classes for art, physical education and music. For students who come to this country with a solid academic background, acquiring sufficient English to be mainstreamed into regular classes can take a year or two.

In guidance to states and local systems in May, U.S. Secretary of Education Arne Duncan recommended schools make it as easy as possible for guardians to register these unaccompanied children while still adhering to requirements that they show proof of vaccination and proof that they reside in the county or city where they will attend school. For instance, schools should accept birth records from foreign countries, and not require that a relative have a driver’s license or that the child have a Social Security number.

Even when students are living with caring relatives, they are at high risk of dropping out, said Marcianna Rodriguez, the English language acquisition department chair at Annapolis High School, a ESOL magnet school in Anne Arundel.

She said students feel their first priority is not their education but working to pay back the smuggler who brought them to the U.S., a bill that she believes often runs between $6,000 and $10,000. It can take a young person as long as five years to repay the debt.

More recently, Rodriguez said, smugglers have become adept at keeping track of the relatives of children who are brought across the border, to make sure money is paid.

“They are very savvy in social media and they know how to track down the families. They can strong-arm them. … Their situation is quite dramatic,” Rodriguez said.

While it is not uncommon for an American teenager to work an after-school job, these teenagers are working much longer hours.

“I have students who have trouble staying awake because they are working 40 hours a week,” she said.

School officials said they are also dealing with girls who have been sexually abused along their journey, teenagers who are rebelling against parents or aunts and uncles they have been recently reunited with, as well as students who are dealing with the bewildering experience of exchanging a rural home with green hills for an apartment complex and a large suburban high school.

Rodriguez said that while the students present great challenges, they offer the chance for a country founded by immigrants to show compassion.

“While you have a moment to offer them education, love, whatever it was they weren’t getting, why would you not do that?”