04/11/2011

In 2001, the torso of a young black boy was pulled out of the Thames in London near the Globe Theater. The body had no head or limbs, so the mystery of who he was and where he came from took a decade to solve. Police called him Adam so the public wouldn’t forget that he was a real boy. (See my 2008 article, Witchcraft Imported by Immigration)

Analysis of the stomach, lungs and bones indicated he had lived most of his life in Nigeria and had come to Britain only a few days before his death. Other tests showed that he had ingested a paralytic agent, when rendered him unable to move as he was cut into pieces during a ritual witchcraft murder.

The case shined a light on the growing problem of human sacrifice in Britain, committed largely by African immigrants who practice witchcraft. The Times of London reported in 2006 that there were 50 such cases in that city alone (”Witch child' abuse spreads in Britain).

Incidentally, witchcraft diversity is alive and well in the Middle East, India and Mexico, as well as Africa. Every case is a reminder that all cultures are NOT morally equal, and immigration from those places welcomes practices that we consider reprehensible crimes.

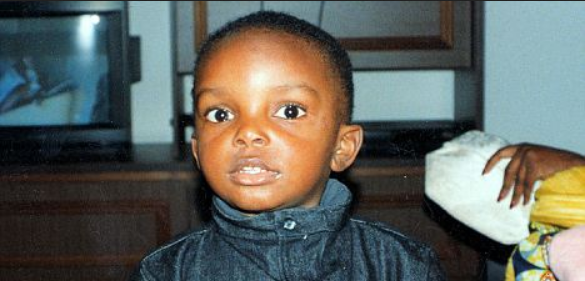

In the case at hand, we now know the name of the little boy who was so brutally murdered — Ikpomwosa — although he will likely be remembered as Adam. But the identity of the killers remains a mystery.

Voodoo and human sacrifice: The haunting story of how Adam, the Torso in the Thames boy, was finally identified, Daily Mail, by Ronke Phillips, April 9, 2011The horror of Adam’s last hours is almost beyond imagination. In his short life, he'd got used to being far away from his West African home and perhaps even accustomed to being passed — like a chattel — from one adult to another.

From the moment he was handed over to a man he didn’t know and brought to London, this poor little boy — five, maybe six years old — would have known only cruelty and terror. In those final hours, he must have been so frightened, so terribly alone.

What I want to believe is that he was so drugged he was unconscious and oblivious of the terrifying events that were about to unfold. But, deep down, I fear that wasn’t so.

Post mortem results, too grim to bear much repetition, reveal that he was still alive when his throat was cut; the West African poison that was found in his intestine is a paralysing agent, not an anaesthetic. There’s a very real chance that Adam would have seen what was coming.

Unable to move and unable to scream, Adam’s last sight on earth would have been of a man approaching him — and then the flash of a razor-sharp knife.

Britain’s first ritual killing had just claimed its victim, an innocent little boy.

Adam’s body was found in the River Thames in London, close to the reconstruction of Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre, on September 21, 2001. The case, however, soon became known as “the torso in the Thames' because when it was found, the body was without its legs, arms and head and had been entirely drained of its blood.

All that was left was the small trunk of a little black boy, its lower half clad in a pair of bright orange shorts. When it was first spotted in the river by a member of the public, he initially assumed he was looking at a barrel.

I’m a correspondent on ITV’s London Tonight programme and within days of the body being discovered I was dispatched to the first police press conference about the case.

It was one of those occasions you never quite forget, with the normal bustle and noise of a busy press conference making way for a stunned silence, with even the most hardened reporters visibly shaken by the horror of what the police were describing.

Some, I know, simply didn’t believe them.

The boy’s head, arms and legs had been removed with skilful precision, we were told, while his lower intestine contained a highly unusual mix of plant extracts, traces of the toxic calabar bean and, perhaps most surprisingly of all, clay particles containing flecks of pure gold.

The police knew that sheer shock value would keep the story in the headlines for a few days but they also knew that a body without a face, without a name, meant there was a real danger of this being perceived as a murder without a victim. So they gave the boy a name.

”His name is Adam,' a visibly affected Commander Andy Baker told us, “and until we can identify him and his family, we will act as his family.'

Ten years on, with the case still unsolved, they are still acting as his family. But, as of last week, there is one key difference — I have been able to tell them Adam’s real name.

Right from the start I'd always felt a close emotional connection to the case, but within weeks came a development that suddenly made that connection personal.

A sophisticated analysis of Adam’s bones for trace minerals that are absorbed from food and water revealed levels of strontium, copper and lead two-and-a-half times higher than would normally be expected in a child living in England.

From the analysis, forensic geologists gradually narrowed down Adam’s likely origin — it matched people who came from West Africa, probably Nigeria.

Well, my parents came from Lagos, the Nigerian capital, and I've been visiting the country all my life.

And if the victim was from Nigeria so, almost certainly, were his killers. Indeed, forensic work carried out by plant experts at Kew Gardens identified the unusual plant extracts found in Adam’s intestine as coming from plants that grow only in the area around Benin City, capital of Edo State in southern Nigeria.

The police team — led by Detective Constable Will O'Reilly and Commander Baker — soon knew three key things about Adam: his exact origin in Nigeria, that the orange shorts he was wearing were sold only in Germany and Austria, and that he had been killed in some sort of ritualistic way by someone convinced they would acquire power from such a barbaric act.

Dr Richard Hoskins, a leading expert on African religion then based at Bath University, came in on the case. He said that the calabar bean was commonly used by African witch doctors for voodoo.

It was exceptionally rare to see the bean used in Britain, but its presence in Adam’s gut — along with that of the other ingredients found there — convinced him this was something utterly horrific: a human sacrifice.

”Adam’s body would have been drained of blood, as an offering to whatever god his murderer believed in,' said Dr Hoskins. “The gold flecks in his intestine were used to make the sacrifice more appealing to that god.'

”The sacrifice of animals happens throughout sub-Saharan Africa and is used to empower people, often as a form of protection from the wrath of gods. Human sacrifice is believed to be the most "empowering" form of sacrifice — and offering up a child is the most extreme form of all. Thankfully, in Africa, it is very rare.'

But why was Adam’s body so grotesquely mutilated? Dr Hoskins, who has been instrumental in helping police with the case, said the precision of the cuts — the knife used was meticulously sharpened between each incision — shows that the dismemberment of the body was all part of the ritual.

In some forms of African witchcraft — particularly those associated with South Africa — dismembered body parts are used in medicine. In some cases, internal organs can be used in potions, and fingers, eyeballs or genitalia are used as charms. Heads and other body parts can be buried in front of homes to keep bad spirits at bay.

But in Adam’s case, the internal organs were intact and Dr Hoskins believes the limbs and head — along with the torso — were all disposed of in the Thames in some form of ritual and that they were never discovered.

After all, the police said that had the tide gone in and out just twice more, Adam’s torso would have been washed out to sea and no one would ever have known about it.

For the Met to be confronted with a ritual murder of this sort was unprecedented. But then, in a twist of fate, immigration police at Glasgow airport arrested a confused Nigerian woman, newly arrived from Germany.

She was claiming asylum, had two young daughters in tow and was making bizarre claims about “extreme religious ceremonies' that her estranged and violent husband was involved in. The Met team quickly headed north.

In the Glasgow flat the woman and her daughters had been put up in, the team made a vital breakthrough, finding a pair of orange shorts, identical to the ones Adam had been wearing.

There was more circumstantial evidence tying this woman, called Joyce Osagiede, to Adam.

In Germany, a young boy had been seen in her care, only to vanish shortly before Adam’s body was found floating in the Thames, while both her estranged husband and another man she associated with had been convicted of offences relating to people trafficking.

But Joyce denied ever having any contact with Adam and insisted she had only ever bought one pair of orange shorts. DNA tests showed she wasn’t related to Adam in any way.

So when it became clear that she had definitely been in Hamburg at the time of the boy’s death, police had no choice but to release her.

Joyce was deported back to Nigeria and, for the next six years, the trail went cold, with the police apparently no closer to identifying Adam or his killers.

But I was convinced Joyce knew who Adam was, and what his real name was. So I kept in touch, both with the investigation team in Britain and my contacts in the Nigerian police force.

Suffering from depression and other health problems, Joyce knew I wanted to speak to her but resolutely turned down all my requests.

Then, in 2008, seven years after Adam’s body had been found in the Thames, I got a call from the Nigerian police: Joyce’s brother, Victor, a former journalist and now a church pastor, said his sister was at last willing to talk.

Indeed, she'd already been talking to officers from Lagos CID, confirming that she'd had custody of a little boy in Germany and that she had dressed him in orange shorts belonging to one of her daughters.

I flew to Lagos with British detectives, only to discover she'd had a nervous breakdown and Nigerian police advised against interviews. I returned home bitterly disappointed without even seeing her. Almost a year would go by without any further contact.

Then, a few weeks ago, came another phone call. Joyce had recovered and was willing to talk to me. Once again, I flew out, first to Lagos and then on to the small airport in Benin City. There we were to meet her brother, Victor, but there was no sign of him and I couldn’t get him to answer his mobile phone. Had something gone wrong again? I let out a sigh of relief as his battered green Ford finally drew up outside. We were back on the case.

We drove for an hour before coming to a halt outside a simple, single-storey, breeze-block dwelling.

This is where Joyce lives, her rent and upkeep paid for by her brother. We went inside and there for the first time I met the woman who I am convinced holds the key to Adam’s tragic story.

My parents taught me Yoruba, while Joyce is a native Edo speaker, so we spoke in English. She was confused and unsure of herself at first, both nervous and slightly aggressive, which I put down to the medication she was on.

But, gradually, she got into her stride and it became clear that the best approach was to let her speak and not to interrupt with too many questions.

Finally, she told me that when she lived in Germany, she had looked after a boy as a favour to a friend, a woman who was not the boy’s mother, but who was about to be deported. Joyce then handed the boy over to a man she calls Bawa, who was taking him to London. The poor child had been passed from person to person like pass the parcel. No one seemed to know where he came from originally.

I then handed Joyce one of a set of photographs that had recently come into my possession, photographs of her with her two daughters. But in three of them there was also a young boy with them. Was this Adam, I wanted to know?

She nodded and then told me what I had travelled 3,000 miles and waited almost ten years to hear.

Joyce told me his native name: “Ikpomwosa.' At last, Adam had a face and a name. Joyce said she handed Ikpomwosa to the man she called Bawa before coming to Britain herself to seek asylum — or “refuge' as she put it.

She claimed she then phoned Bawa to ask about the boy and was told he was dead.

I asked her if she knew who had killed him. “I’m a mother, I have children,' she replied. “I can’t kill someone’s child.'

She hesitated, but then — insisting she didn’t know the group of people involved — admitted: “They used him for a ritual in the water.'

The confirmation came as a relief, but also as a shock. Human sacrifice in London? It’s unthinkable.

But while the Met said it is unprecedented, stories of abuse and child trafficking among African communities in the capital are not unknown. In 2005, three people originally from Angola were found guilty at the Old Bailey of torturing an eight-year-old girl they thought was a witch. The cruelty started when a boy told his mother that the girl had been practising witchcraft.

The girl was starved, cut with a knife and hit with a belt and shoes to “beat the Devil out of her'. She had chilli peppers rubbed in her eyes and, at one stage, was put into a laundry bag to be thrown into the river. She was saved from drowning only when one of the perpetrators warned that they would be sent to prison if caught and they decided against it.

This child, an orphan, was the victim of trafficking, like Adam — she was brought into the UK from Angola by her aunt, who had passed her off as her daughter.

After the case, representatives from the Government got together with the police, social services, African community leaders and church representatives to discuss ways of protecting young African children, who endure horrendous treatment at the hands of bogus practitioners performing what they claim are exorcisms and other rituals.

Dr Hoskins said the most likely explanation for Adam’s death is that the murderer was a trafficker of children and drugs who had sacrificed poor Adam in order to give him power to evade the authorities.

Whatever the truth, at last we are one step closer to understanding the appalling fate of this little boy.

Yes, Joyce is volatile, has mental health issues and the British police still have to corroborate everything she said, but I still listened transfixed, as the missing pieces of a ten-year-old puzzle finally began to fall into place.

I hope this breakthrough will help to spark new progress in this tragic case. Ten years after his poor, mutilated little body was fished out of the Thames, the boy known as Adam may now have a face and a name, Ikpomwosa.

But we have yet to find his killers.