"Does Raj Chetty Practice What He Preaches?"

By Steve Sailer

12/21/2023

I snarked five years ago about the brilliant staff assembled by Raj Chetty, now the Bill Ackman Professor of Economics back at Harvard, to do breakthrough analyses of anonymized official data from the IRS, Census, College Board, and the like:

Stanford economist Raj #Chetty has assembled an expert team of crack data analysts (shown below) to figure out why blacks and Indians (Americans, not Asian) have lower incomes.

One thing Chetty knows: it _couldn’t_ have anything to do with IQ and race.https://t.co/Wgbsn4n6NR pic.twitter.com/t8hKkEfoOQ

— Steve Sailer (@Steve_Sailer) March 22, 2018

Chetty is of course a South Asian. Of the other 12 people in the photo, one is almost completely blocked, one is a white woman, and the the other ten appear to be all white male or at least partly white male.

Now, from the Chronicle of Higher Education:

Does Raj Chetty Practice What He Preaches?

His research skewers elitist systems. But some former employees say his lab is part of the problem.

By Nell Gluckman and Francie Diep

DECEMBER 20, 2023Raj Chetty has reshaped our understanding of social mobility in the United States.

The Harvard University economist’s research, often featured in The New York Times, has renewed scrutiny of America’s identity as “the land of opportunity.” In 2015, Chetty and Nathaniel Hendren, a frequent co-author, posted a detailed analysis of every county in the U.S. sorted by how likely their poor children are to move up the socioeconomic ladder.

As I pointed out in my lengthy analysis “Moneyball for Real Estate” of Chetty’s rather opaque paper, the best county in the USA for blue collar kids to grow up in is ultra-conservative Sioux County, Iowa, where 40% are members of the Dutch Reformed Church and 80% are church-goers. In ironic contrast, the worst county to grow up in is the Sioux Indian reservation in Pine Ridge, South Dakota.

The basic finding of Chetty’s data on social mobility, as I pointed out in 2013 in the first week he started publishing it (in my post: “Breakthrough Study: Poor Blacks Tend to Stay Poor, Black“), is that whites regress toward higher mean incomes than do blacks or American Indians. But there are more minor influences as well, such as that north central Protestants and Mormons do better than other blue collar whites.

In 2018, Chetty, Hendren, and two other co-authors showed that Black men consistently earn less than their white peers from families with the same incomes, once they become adults.

It’s called blacks regressing toward a lower mean income than whites.

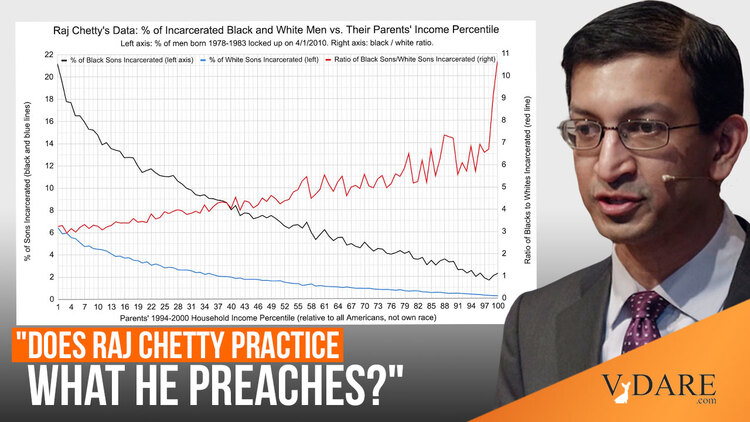

More strikingly, Chetty found that black men are imprisoned three to ten times as often as their white peers who had the exact same incomes growing up:

This is a pretty epic finding by Chetty. Virtually nobody thought they could get their hands on all this confidential government data until Chetty resolved to do it.

My graph of Chetty’s data is more jaw-dropping than his, but if you study Chetty’s own graph closely,

you’ll see he’s come up with the same answer as I have: that while the extraordinarily high black crime is partly correlated with income differences, a huge fraction is due to racial differences. Yet, almost nobody other than me figured out that’s what he was saying.

Chetty’s work has been used as a rallying cry to urge municipalities to do more to help their poorest residents reach the middle class.

Chetty was confident way back in 2013 that he was about to discover a whole bunch of ways for American society to be reorganized so that poor people could move up in the world over the generations. But, instead, he’s mostly come up with one good insight over the last decade: Mothers of black sons — move, right now, as far away from your nephews as possible before they recruit your son, their cousin, to join their street gang. Instead, go move to some white exurb far from your kin where the neighborhood boys play Grand Theft Auto rather than commit Grand Theft Auto.

But virtually nobody other than me grasps what Chetty is trying to tell them because he’s not going to phrase his findings as clearly as I will. After all, he’s the the William A. Ackman Professor of Economics at Harvard University and he intends to stay that way even if nobody other than deplorable Sailer readers ever comprehends what he’s found. It would be swell if his findings were made clear to black mothers, but he’s not going to sacrifice his brilliant career by first making his discoveries clear to white liberal social justice warriors so they can cancel him.

In contrast to me, the media seems convinced that Chetty’s data confirms liberal pieties. Myself, having looked over Chetty’s numbers carefully, I find that either he has confirmed my picture of how the world the works, or I’ve changed my worldview to conform to his findings.

Chetty has also dramatically recast how colleges are measured. Among his landmark findings: Many of the most selective institutions enroll more students in the top 1 percent of family income than in the bottom 60 percent. In recent months, he and his colleagues have revealed the extent to which many selective colleges put their thumbs on the scale for students from very rich families, as well as how strongly SAT scores correlate with family wealth….

… Economics is a notoriously white and male field, and Chetty has been credited with helping to change that.

Oh, boy … There’s definitely a shortage of South Asian academics these days. From The Atlantic in 2019:

His mother, Anbu, … showed the greatest academic potential of her five siblings … In 1962, Anbu married Veerappa Chetty, a brilliant man from Tamil Nadu whose mother and grandmother had sometimes eaten less food so there would be more for him. Anbu became a doctor and supported her husband while he earned a doctorate in economics. By 1979, when Raj was born in New Delhi, his mother was a pediatrics professor and his father was an economics professor who had served as an adviser to Prime Minister Indira Gandhi.

It’s almost as if Raj Chetty had been eugenically bred to be smart and successful. But of course that’s pseudoscience, so he turned out dumb and unsuccessful:

When Chetty was 9, his family moved to the United States, and he began a climb nearly as dramatic as that of his parents. He was the valedictorian of his high-school class, then graduated in just three years from Harvard University, where he went on to earn a doctorate in economics and, at age 28, was among the youngest faculty members in the university’s history to be offered tenure. In 2012, he was awarded the MacArthur genius grant. The following year, he was given the John Bates Clark Medal, awarded to the most promising economist under 40. (He was 33 at the time.) In 2015, Stanford University hired him away. Last summer, Harvard lured him back to launch his own research and policy institute, with funding from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative.

And Bill Ackman.

In 2003, after earning his doctorate, Chetty moved to UC Berkeley for his first job. He was, at the time, the only person in his immediate family — his parents and two older sisters, both biomedical researchers — who had not published a paper.

Both of Chetty’s parents descend from the Chettiar caste, a mercantile group historically involved in banking, and the kids were raised to carry on their cultural heritage. They learned Tamil in addition to Hindi. Chetty’s sisters married men with Chettiar backgrounds. Chetty rejects the caste system, though he first met his wife, Sundari, after one of his sisters got to know her through the Chettiar community. (Sundari is a stem-cell biologist.)

The Chettiar caste definitely practices social mobility!

Back to the Chronicles of Higher Education:

Born in India, his family moved to the U.S. when he was 9. He earned his economics Ph.D. from Harvard at age 23, won a MacArthur Fellowship in 2012, and was elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 2018. After stints as a faculty member at the University of California at Berkeley, Harvard, and Stanford University, he returned to Harvard in 2018, where he and two colleagues founded a research group called Opportunity Insights. He also started an introductory economics course that’s been lauded for attracting more diverse students to economics. Opportunity Insights has garnered tens of millions of dollars in grants from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, and others.

But inside the lab, Chetty and his colleagues have not always practiced what their research preaches, several former employees say. When hiring for their prestigious “pre-doctoral fellowship” program, for instance, the lab uses a rubric that explicitly favors students from the very colleges that its own research has called out for reinforcing elitist systems. Opportunity Insights didn’t have its first Black pre-doc until 2021.

How many black law clerks did Ruth Bader Ginsburg have?

As of 2018, she had had one in the first 38 years of career on the bench. (Not surprisingly, he was very good: one of the three finalists for an Obama Supreme Court nomination.)

Seven former employees who spoke to The Chronicle about their experiences were bothered by what they saw as contradictions between the lab’s practices and its stated values.

After landing the fellowship, some employees said they were also disturbed to find a culture of overwork that left them fried but feeling forced to impress in order to secure a letter of recommendation to a top Ph.D. program. For some employees, it took a toll on their health. Harvard even reviewed the lab following claims of unsustainable working hours. …

“If you’ve been at this handful of colleges we’re talking about, you have been taught probably by recent Nobel laureates, or students of Nobel laureates, about methods they developed in the last five years,” Chetty said. “We can feel that very clearly when we’re doing interviews or talking with students after we’ve hired them here.”

Chetty acknowledged the lab had room to improve. But he argued that it was much more diverse than other, similar pre-doc programs, and than the field’s doctoral programs. “We’re proud of that,” he said. “We view that as basically part of our mission. We’re trying to advance equity in opportunity and through our research.”

Interviews with dozens of former Opportunity Insights employees, several of whom would only speak anonymously out of fear of damaging their career prospects, painted a nuanced picture of what it was like to work there. At best, the trailblazing lab is making a real effort to be true to its stated values while constrained by larger forces of homogeneity and elitism within economics.

Or maybe the smartest, hardest working young economists tend to have smart, hard working parents?

At worst, its leaders have been content to let the lessons of their research go unrealized within their own organization.

Or maybe you should listen to me explain what the lessons of Chetty’s research really are, not Chetty? After all, why would I lie about what Chetty is digging up? In contrast, why would Chetty obfuscate his Sailerish findings? To avoid being canceled, of course.

Over the past decade, big data has revolutionized economics. …

Some economists hoped the advent of pre-doctoral fellowships would also help diversify the profession. The field is striking for its lack of representation. A paper published this fall in the Journal of Economic Perspectives reported that 65 percent of U.S.-born economics-Ph.D. recipients have a parent with a graduate degree. That was the greatest share among 14 broad Ph.D. fields — like humanities, biological sciences, and business — the researchers analyzed. “Economics is one of the least socioeconomically diverse fields,” the paper’s authors wrote.

It’s almost as if economists tend to grow up in families that are comfortable thinking intelligently about money and thus tend to have a lot of it. For example, former Harvard president and former secretary of the treasury Larry Summers is the son of two professors of economics and the nephew of two Nobel winning economists (Paul Samuelson was his father’s brother and Kenneth Arrow was his mother’s brother.)

That paper also found that among U.S.-born doctorate holders in those 14 fields, economics Ph.D.s are the least likely to be underrepresented racial and ethnic minorities, the least likely to be first-generation college students, and among the least likely to be women. (Math, engineering, and computer science have fewer female doctorates).

And, I guess, judging from Nobel Prizes, probably the highest percentage of Jews.

In theory, pre-doc positions could help to level the playing field. They give recent graduates a chance to try out life as a researcher before committing to a six-year Ph.D. This opportunity is especially important for people who didn’t attend a college with robust research programs. Pre-docs are seen as a good alternative to master’s degrees because they’re paid — at roughly $45,000 to $65,000 per year, according to one survey. (The pre-docs at Opportunity Insights make $65,000, Chetty said.)

Known for its prestige and mission, Opportunity Insights is a sought-after destination for prospective pre-docs. The group receives some 500 applications a year for the roughly half-dozen spots that open up annually. To sort through the stacks of materials, the lab created a rubric that assigns points based on different measures. Current pre-docs use the rubric to help make a first cut in the applicant pool for the successive class.

In a 2021 copy of the rubric obtained by The Chronicle, “caliber of university” was worth two points, out of nine. The other criteria were research experience, worth four points; grades, worth two points; and a bonus point that could go to applicants “who truly stand out,” have a unique skill or perspective, or go “above and beyond.” …

A college’s caliber is determined by a list the lab leaders maintain. One version of the list obtained by The Chronicle catalogs the 75th-percentile math SAT scores at more than 1,200 colleges. The rubric stipulates that the full two points go to alumni of colleges where the math SAT scores of top admitted students were 790 or higher; 1.5 points for scores of 750 to 789; and one point for 700 to 749.

Based on these copies of the rubric and calibrating list, applicants from the California Institute of Technology, Carnegie Mellon University, Swarthmore College, and 32 other colleges, got the full two points. Graduates of the University of California at Irvine, Rutgers University at New Brunswick, Kenyon College, and 68 other colleges got one point. Public universities that had lower SAT scores, but which were their state’s flagship, as well as “top” historically Black colleges, got a half point. All other HBCUs, along with about 1,000 other colleges — the vast majority of the institutions listed — got zero points. (It’s not clear which HBCUs were considered “top.”)

Chetty was a Harvard professor, then he was lured to Stanford, then Harvard and billionaire Bill Ackman lured him back to Harvard. It’s not clear if any HBCUs were ever in the running for Professor Chetty’s services.

Sarah Oppenheimer, executive director of Opportunity Insights,

What have people named “Oppenheimer” ever accomplished in math-intensive fields like stock investing, cartelizing diamonds, and blowing up Hiroshima?

… Several former employees saw the rubric as conflicting with the findings of Opportunity Insights’ own research. Data from the lab’s latest college-admissions paper show just how tightly students’ SAT scores correlate to their families’ incomes. That paper also showed that at “Ivy Plus” colleges — defined as the eight Ivy League institutions, plus Duke University, MIT, Stanford, and the University of Chicago — family income has an outsize influence on admissions. Even among students who have the same SAT scores, students from families in the top 1 percent of American incomes are more than twice as likely to get into an Ivy-Plus college as students from middle-class families.

“We conclude that highly selective private colleges currently amplify the persistence of privilege across generations,” reads the paper’s abstract.

… In interviews, the lab’s leaders said they saw benefits to hiring graduates of high-scoring colleges. The pre-docs often learn from one another, Chetty said, so it’s helpful to have at least some who come in highly trained. “If you’re trying to do the best research,” he said, “the reality is, I think it is valuable to hire students from top colleges.”

As for why the lab defines “top colleges” using their students’ math SAT scores, Friedman acknowledged it’s not a perfect measure, but, he said: “We’re trying to be consistent about how we do it, in a way that isn’t just us saying, ‘Oh, we like that school. We don’t like that school.’” Even as Opportunity Insights’ research has shown a close correlation between SAT score and family income, it’s also found that among students of the same race or level of family wealth, higher scores are associated with better incomes and jobs later in life. …

Chetty said he was aware that favoring prestigious colleges could “cut against having a diverse pool.” To account for that, Chetty said the lab also keeps an eye out for applicants “from those backgrounds that are less widely represented” and advances most of them, regardless of how the rubric scores them.

Underrepresented perspectives in the lab might mean skills, such as computer programming, or being from parts of the country or world that are unusual for Opportunity Insights, Chetty said. A large share of underrepresented-racial-minority applicants get the coding test and an interview, he said, adding that pre-docs working on admitting the next class weren’t told about this aspect of the hiring. He said he didn’t want to “create the social dynamics of: ‘This person was admitted through one process, and then this person got some other consideration.’”

The hiring process has yielded a relatively diverse group of pre-docs, the lab leaders say: Since 2018, about 15 percent of their pre-docs have been Hispanic or Black, and 44 percent are women or nonbinary. For comparison, just 4 percent of doctoral students in economics are Hispanic, Black, American Indian, or Pacific Islander, according to the latest available data from the National Science Foundation. Thirty-six percent of current economics Ph.D. students are women.

So after 2018 when I tweeted that photo of his staff, Chetty shifted over to affirmative action hiring, and now his staffers are whining about how hard he works them?

But the lab’s pre-doc alumni overwhelmingly hail from colleges of high “caliber,” as the rubric defines it. Of 76 former pre-docs for whom The Chronicle could identify an undergraduate institution — out of 81 pre-docs in the lab’s history — only one non-international student attended a college that received zero points in the 2021 copy of the rubric and calibrating list.

How many students at zero point colleges earn a 790 on their math SAT?

The problem isn’t the rubric, the lab’s leaders argue. It’s that less than 2 percent of people who apply to Opportunity Insights come from zero-scoring colleges.

Any efforts the lab made to specifically recruit Black pre-docs yielded no results until recently. By 2020, after nationwide protests sparked by a police officer’s murder of George Floyd, the lab still had never hired a Black pre-doc. Some staffers saw the situation as conflicting with the moral thrust of the lab’s research.

Shouldn’t a lab’s research have primarily a scientific thrust?

At least two classes of Opportunity Insights pre-docs advocated for changes to how pre-docs are hired, as did Maddie Marino, Chetty’s assistant in 2019 and 2020. Several pre-docs in the 2019-21 class compiled data for Chetty on who applied and got into the lab, showing which undergraduate programs were not well represented among applicants.

In other words, once Chetty started doing affirmative action hiring in 2019, his new hires roasted him for not doing more affirmative action hiring.

And they complained to the press about how exhausted they were.