Even in Nearly 80% White Asheville, North Carolina, Gun Violence Is DEFINITELY A "Black-Person Thing" …

By Paul Kersey

02/18/2021

Earlier: How Much Blood Does Black Lives Matter Have On Its Hands?

Spoiler Alert: in 11 percent black Asheville, North Carolina, gun violence is a “black-person thing.”

Multiagency collaboration seeks to stop gun violence, MountainX.com, February 13, 2021

Can rising gun violence in Asheville be stopped in its tracks by roughly $200,000 of funding supporting a year of on-the-ground programming? Probably not. But that doesn’t mean community organizations don’t plan to try.

Over the last year, the urgent need to address the interrelated causes and impacts of gun violence, systemic racism and poverty grew even more pressing. In 2020, the Asheville Police Department reported a five-year high for calls related to gun discharges and shootings, the vast majority of which involved Black men. Community members grew tired of witnessing the disproportionate impact of gun violence on their friends and neighbors, explains Tiffany Iheanacho, Buncombe County’s justice services director, prompting county leaders to look for new solutions.

In June, Buncombe County’s child fatality review team identified gun violence as a growing threat to children in Asheville. Buncombe County’s Justice Resource Advisory Council passed a proclamation declaring racism a public safety emergency in July.

In early January, Buncombe County announced a new partnership with four community organizations — the SPARC Foundation; Umoja Health, Wellness and Justice Collective; My Daddy Taught Me That; and the Racial Justice Coalition — to develop a community-led strategy to help address gun violence. Funded using a portion of the county’s $1.75 million Safety and Justice Challenge grant, which aims to reduce jail populations, the team plans to provide residents comprehensive services to support the journey out of poverty and trauma.

“In this day and age, it’s really hard to come up with a novel idea about anything,” says Jackie Latek, executive director of the SPARC Foundation. “What we’re doing here is taking existing programs that have evidence and research behind them that have worked, and we’re pulling those programs together.”

From redlining to predatory lending; from the era of mass incarceration to the enormous achievement gap between Black and white students enrolled in Asheville City Schools, gun violence cannot be solved without understanding the history of racism that drove many Black communities into poverty, Thomas argues. “You have to understand the history so the solution will not be seen as charity, because the solution will require a lot of resources, from people to money to infrastructure,” he says.

Residents in communities experiencing high rates of violence are likewise tired of watching programs come and go within a few years, Latek adds, making continued county support all the more important. “If we’re going to push this rock up a hill, don’t pull our people away from us when we get halfway up,” she says. “We need to get this rock to the top, before it comes crashing back down on us.”

Buncombe County hopes to continue funding the program after its first year, says Hannah Legerton, the Justice Services grants manager. Staff has applied for an additional year of Safety and Justice Challenge grant funding from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation; if awarded, the renewal includes a one-year program extension. Longer term, the county is beginning to look for outside funding streams to continue projects that have demonstrated success, she says.

If the city of Asheville wanted to get involved, Thomas suggests using a portion of the Asheville Police Department’s $30.1 million annual operating budget. As activists continue to advocate for a 50% cut to the APD budget, a fraction of that funding for a program like this could have a huge impact, he says.

“Gun violence isn’t just a Black-person thing, it’s not just a poor-person thing, it’s an everybody problem — you could get shot or robbed if you’ve been doing everything right in your life,” Thomas says. “With this program, we’re trying to work a miracle with a hope and a wish.”

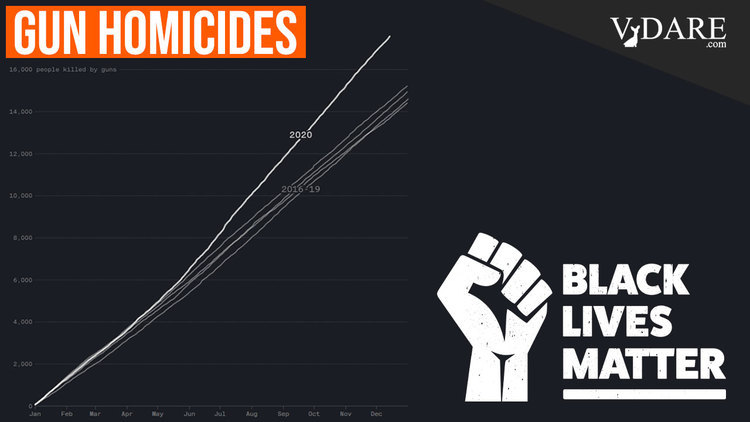

Black gun violence can’t be blamed on redlining, predatory lending, mass incarceration, the racial gap in learning/education or poverty, but simply on black individuals deciding to pull the trigger of a gun and target other black individuals, which collectively aggregate to being the "vast majority" of gun violence in Asheville. Or for that matter, the state of North Carolina or the United States of America.