Former SPLC Employee: "We Were Part of the Con, and We Knew It."

By Steve Sailer

03/22/2019

From The New Yorker:

The Reckoning of Morris Dees and the Southern Poverty Law Center

By Bob Moser 11:05 A.M.

Moser was employed by the SPLC from 2001 to 2004 — i.e., a long time ago. And yet the SPLC continued to be promoted by the Great and Good as the final, unquestionable arbiter of Virtue vs. Evil until, hopefully, last week.

The firing of Morris Dees, the co-founder of the S.P.L.C., has flushed up uncomfortable questions that have surrounded the organization for years.

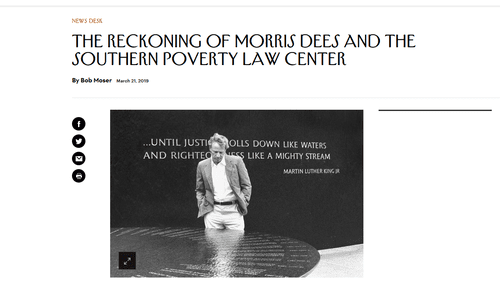

In the days since the stunning dismissal of Morris Dees, the co-founder of the Southern Poverty Law Center, on March 14th, I’ve been thinking about the jokes my S.P.L.C. colleagues and I used to tell to keep ourselves sane. Walking to lunch past the center’s Maya Lin–designed memorial to civil-rights martyrs, we’d cast a glance at the inscription from Martin Luther King, Jr., etched into the black marble — “Until justice rolls down like waters” — and intone, in our deepest voices, “Until justice rolls down like dollars.”

The Law Center had a way of turning idealists into cynics; like most liberals, our view of the S.P.L.C. before we arrived had been shaped by its oft-cited listings of U.S. hate groups, its reputation for winning cases against the Ku Klux Klan and Aryan Nations, and its stream of direct-mail pleas for money to keep the good work going. The mailers, in particular, painted a vivid picture of a scrappy band of intrepid attorneys and hate-group monitors, working under constant threat of death to fight hatred and injustice in the deepest heart of Dixie. When the S.P.L.C. hired me as a writer, in 2001, I figured I knew what to expect: long hours working with humble resources and a highly diverse bunch of super-dedicated colleagues. I felt self-righteous about the work before I’d even begun it.

The first surprise was the office itself. On a hill in downtown Montgomery, down the street from both Jefferson Davis’s Confederate White House and the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, where M.L.K. preached and organized, the center had recently built a massive modernist glass-and-steel structure that the social critic James Howard Kunstler would later liken to a “Darth Vader building” that made social justice “look despotic.”

… But nothing was more uncomfortable than the racial dynamic that quickly became apparent: a fair number of what was then about a hundred employees were African-American, but almost all of them were administrative and support staff — “the help,” one of my black colleagues said pointedly. The “professional staff” — the lawyers, researchers, educators, public-relations officers, and fund-raisers — were almost exclusively white. Just two staffers, including me, were openly gay.

During my first few weeks, a friendly new co-worker couldn’t help laughing at my bewilderment. “Well, honey, welcome to the Poverty Palace,” she said. “I can guaran-damn-tee that you will never step foot in a more contradictory place as long as you live.”

“Everything feels so out of whack,” I said. “Where are the lawyers? Where’s the diversity? What in God’s name is going on here?”

“And you call yourself a journalist!” she said, laughing again. “Clearly you didn’t do your research.”

In the decade or so before I’d arrived, the center’s reputation as a beacon of justice had taken some hits from reporters who’d peered behind the façade. In 1995, the Montgomery Advertiser had been a Pulitzer finalist for a series that documented, among other things, staffers’ allegations of racial discrimination within the organization. In Harper’s, Ken Silverstein had revealed that the center had accumulated an endowment topping a hundred and twenty million dollars while paying lavish salaries to its highest-ranking staffers and spending far less than most nonprofit groups on the work that it claimed to do. The great Southern journalist John Egerton, writing for The Progressive, had painted a damning portrait of Dees, the center’s longtime mastermind, as a “super-salesman and master fundraiser” who viewed civil-rights work mainly as a marketing tool for bilking gullible Northern liberals. “We just run our business like a business,” Dees told Egerton. “Whether you’re selling cakes or causes, it’s all the same.”

Co-workers stealthily passed along these articles to me — it was a rite of passage for new staffers, a cautionary heads-up about what we’d stepped into with our noble intentions. Incoming female staffers were additionally warned by their new colleagues about Dees’s reputation for hitting on young women. And the unchecked power of the lavishly compensated white men at the top of the organization — Dees and the center’s president, Richard Cohen — made staffers pessimistic that any of these issues would ever be addressed. …

… another former writer at the center said, speculating about what might have prompted the move. “It could be racial, sexual, financial — that place was a virtual buffet of injustices,” she said. Why would they fire him now? …

The staffers wrote that Dees’s firing was welcome but insufficient: their larger concern, they emphasized, was a widespread pattern of racial and gender discrimination by the center’s current leadership, stretching back many years. …

The controversy erupted at a moment when the S.P.L.C. had never been more prominent, or more profitable. Donald Trump’s Presidency opened up a gusher of donations; after raising fifty million dollars in 2016, the center took in a hundred and thirty-two million dollars in 2017, much of it coming after the violent spectacle that unfolded at the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, that August. George and Amal Clooney’s justice foundation donated a million, as did Apple, which also added a donation button for the S.P.L.C. to its iTunes store. JPMorgan chipped in five hundred thousand dollars. The new money pushed the center’s endowment past four hundred and fifty million dollars

Most people are assuming that Morris got fired last week for being a horndog and/or a Good Old Boy who doesn’t think highly of blacks. But that was evident for decades. So what happened lately to get him fired rather than (forcibly) let him retire at age 82?

Maybe a tape turned up of him using the N-word? Or maybe somebody taped him talking honestly about the SPLC’s donors? I dunno.

Or what about something financial? It would be interesting to know just how certain it is that every penny the SPLC claims to have piled up is really sitting there in their onshore and offshore accounts.

Here’s the SPLC’s auditor’s statement. It seems pretty reassuring. I think.

So, I dunno …

Back to The New Yorker:

, which is more than the total assets of the American Civil Liberties Union, and it now employs an all-time high of around three hundred and fifty staffers. But none of that has slackened its constant drive for more money.

Can you imagine how much Morris could have reaped for the SPLC off of New Zealand if he hadn’t been fired the day before?

… In the late sixties, Dees sold the direct-mail operation to the Times Mirror Company, of Los Angeles, reportedly for between six and seven million dollars. But he soon sniffed out a new avenue for his marketing genius. …

A decade or so later, the center began to abandon poverty law — representing death-row defendants and others who lacked the means to hire proper representation — to focus on taking down the Ku Klux Klan. This was a seemingly odd mission, given that the Klan, which had millions of members in the nineteen-twenties, was mostly a spent force by the mid-eighties, with only an estimated ten thousand members scattered across the country. But “Dees saw the Klan as a perfect target,” Egerton wrote. For millions of Americans, the K.K.K. still personified violent white supremacy in America, and Dees “perceived chinks in the Klan’s armor: poverty and poor education in its ranks, competitive squabbling among the leaders, scattered and disunited factions, undisciplined behavior, limited funds, few if any good lawyers.” Along with legal challenges to what was left of the Klan, the center launched Klanwatch, which monitored the group’s activities. Klanwatch was the seed for what became the broader-based Intelligence Project, which tracks extremists and produces the S.P.L.C.’s annual hate-group list.

The only thing easier than beating the Klan in court — “like shooting fish in a barrel,” one of Dees’s associates told Egerton — was raising money off Klan-fighting from liberals up north, who still had fresh visions of the violent confrontations of the sixties in their heads. The S.P.L.C. got a huge publicity boost in July, 1983, when three Klansmen firebombed its headquarters. …

By the time I touched down in Montgomery, the center had increased its staff and branched out considerably — adding an educational component called Teaching Tolerance and expanding its legal and intelligence operations to target a broad range of right-wing groups and injustices — but the basic formula perfected in the eighties remained the same. The annual hate-group list, which in 2018 included a thousand and twenty organizations, both small and large, remains a valuable resource for journalists and a masterstroke of Dees’s marketing talents; every year, when the center publishes it, mainstream outlets write about the “rising tide of hate” discovered by the S.P.L.C.’s researchers, and reporters frequently refer to the list when they write about the groups. …

For those of us who’ve worked in the Poverty Palace, putting it all into perspective isn’t easy, even to ourselves. We were working with a group of dedicated and talented people, fighting all kinds of good fights, making life miserable for the bad guys. And yet, all the time, dark shadows hung over everything: the racial and gender disparities, the whispers about sexual harassment, the abuses that stemmed from the top-down management, and the guilt you couldn’t help feeling about the legions of donors who believed that their money was being used, faithfully and well, to do the Lord’s work in the heart of Dixie. We were part of the con, and we knew it.

Outside of work, we spent a lot of time drinking and dishing in Montgomery bars and restaurants about the oppressive security regime, the hyperbolic fund-raising appeals, and the fact that, though the center claimed to be effective in fighting extremism, “hate” always continued to be on the rise, more dangerous than ever, with each year’s report on hate groups. “The S.P.L.C. — making hate pay,” we’d say.