From Derb’s Email Bag: Janet Banana, R.I.P., Jim Crow v. Jim Snow, And Toppling King George III

08/10/2021

Just a few from the Derbyshire email bag.

• Brainteaser. There is a worked solution to my July brainteaser here. Please note, however, that I misstated the conditions of the IMO final exam in my diary. I described it as a "6-problem, 4½-hour competitive exam." In fact it’s a 9-hour test, with 4½ hours for the first three problems and 4½ hours for the last three.

• Janet Banana, R.I.P. In my July 30th podcast I lamented — not for the first time, and on entirely onomastic grounds — the 2003 passing of Zimbabwe’s first president, the Rev. Canaan Banana, the only head of state in modern times whose national legislature made it a crime to joke about his name.

A listener has chidden me for having failed to note the death on July 29th this year of the Rev. Banana’s widow, Janet Banana. Duly noted.

Should you wish to know more about the Rev. and Mrs. Banana, the widow’s death has inspired a whole bunch of interesting obituaries.

• Jim Crow v. Jim Snow. A reader of my musings on this topic has directed my attention to this new book by Bowling Alone author Robert Putnam. The book’s title is The Upswing, subtitle: "How America Came Together a Century Ago and How We Can Do It Again." The Upswing was published last October.

The book, says my reader, offers some support to my doubts about Jim Snow being any improvement on Jim Crow. It seems to agree (he writes) that "before the mid-1960’s all was getting better, but then shortly after all trends were plunging." He offers a rather striking graph from Putnam’s book.

Prof. Putnam, who is an old-style liberal — the gentlemanly sort, not a witch-hunter, and in fact a very good quantitative social scientist — would be horrified to think of his book being brought forward in evidence of my Jim Snow / Jim Crow thesis. Still, it wouldn’t be the first time his scrupulously empirical researches have directed him to a conclusion he finds temperamentally unwelcome. (And see Chapter 2 of We Are Doomed.)

Is it just me, or does anyone else have the impression of a slow-wakening awareness, on the part of people who think deeply about our society and culture, that the U.S.A. took a dramatically wrong turn in the mid-1960s? In further evidence I offer Christopher Caldwell’s 2021 book The Age of Entitlement (although there is much more to Caldwell’s book than just that).

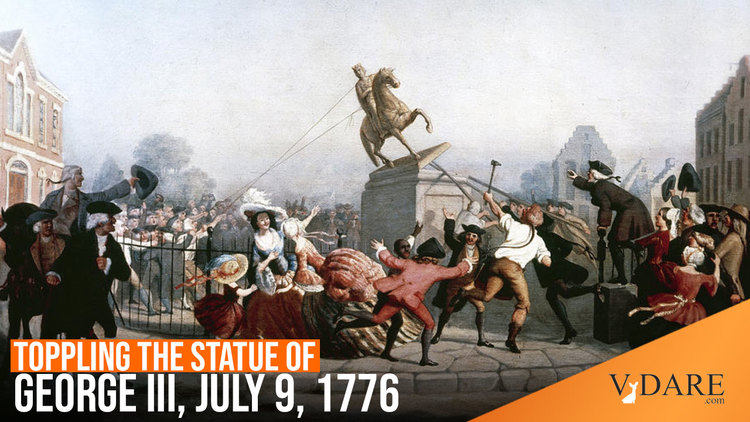

• Iconoclasm. In my July Diary I had a segment on the toppling of statues, inspired by a review I'd read of a new book by Alex von Tunzelmann. The first statue-toppling described in this book, the reviewer tells us, was "one of George III in New York, made of gilded lead and erected in 1770 but pulled down just six years later by American revolutionaries."

A friend adds some colorful details:

After the French and Indian War … the grateful colonists, or at least the government, set up the gilded lead statue of George III in Bowling Green, at the southern end of Broadway. Of course, it was the after-effects of the war that eventually led to the Revolution, and in the lead-up to that, the statue was the target of vandalism. That, and papers blowing down Broadway would collect at the base of the statue, a less intentional form of lèse-majesté. So in 1773, a cast-iron fence was erected around the park. To drive the point home, every twelfth fencepost or so was larger and topped with a royal crown.

A few days after July 4, 1776, the Declaration of Independence made its way to New York and was read publicly. A mob then rushed to the statue and tore it down, and, the legend says, the lead statue was melted down and "returned to the British ball by ball."

It’s not clear how true that last detail is — the head at least was saved and sent back to England, and pieces of the statue still survive in various museums. But the bulk is gone, so it’s not unlikely the legend is mostly true.

Anyway, as part of the statue-toppling, the crowd also lopped off the crowns from the fenceposts. Otherwise, the fence, almost 250 years old, is still completely intact. Every time I would be down in that neighborhood, I'd run my finger on the still-jagged tops of the larger posts and feel a bit of history.