Geekwire: Presidential Candidates Ignore Automation Job Challenge

08/04/2016

Last winter I wrote an article for The Social Contract titled Presidential Candidates: Why Is Automation’s Job Destruction Not Being Debated? (PDF version here). That piece covered the whole primary field, which turned out to be easy because none of the various 20+ contenders discussed the looming economic and social threat of machines and software replacing humans.

Naturally, I pointed out that immigrant workers would not be required in America’s automated future.

Interestingly, Geekwire’s article on the automation topic mentions immigration, but tech expert Moshi Vardi thinks that potential immigrants may be dissuaded from coming if they learn there is more competition for low-skilled jobs — really? Professor Vardi has been effectively warning about the technology threat to society, but he may not fully grasp the magnetic pull factor of American freebies on the third world.

The report below confirms my assessment that it is unwise for first-world nations to continue admitting immigrants, particularly with lower skill levels (hello, Germany!), because a growing underclass of unemployed persons will create social problems in the future.

In short:

Automation makes immigration obsolete.

Other than ending immigration, the fixes for the long-term future challenges caused by smart machines are rather limited. A basic income program for all is briefly discussed in the piece below, but that proposal sounds difficult to implement — not to mention being the mother of all illegal immigrant magnets.

Neither Trump nor Clinton is addressing the biggest challenge to jobs: automation, Geekwire, by Alan Boyle, July 30, 2016

Presidential candidates Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump are both promising to bring good-paying jobs back to America, but analysts say neither of them has addressed one of the biggest challenges looming ahead: the impact of automation and the rise of artificial intelligence.

Some argue that the challenge will soon become impossible to ignore.

“Job losses due to automation and robotics are often overlooked in discussions about the unexpected rise of outside political candidates like Trump and Bernie Sanders,” Moshe Vardi, an expert on artificial intelligence at Rice University, said before this month’s conventions.

Previously: AI prophets say robots could spark unemployment — and a revolution

Vardi pointed out that manufacturing employment has been falling for more than 30 years, and yet U.S. manufacturing output is near its all-time high.

“U.S. factories are not disappearing: They simply aren’t employing human workers,” Vardi said.

That trend is hitting America’s working class particularly hard.

“While manufacturing is the most striking example, there is considerable evidence that automation is transforming other sectors of the labor market, and there’s increasing evidence that this leads to economic stratification, the decline of the middle class and the subsequent undercurrent of misery that is driving support of Trump,” Vardi said.

The transportation sector is likely to be next, as autonomous vehicles start moving products and people. It’s widely recognized, for example, that the biggest expense for ride-share services like Uber is the driver’s pay.

In an email to GeekWire, Vardi said the automation of transportation could eliminate millions of jobs in the United States. “This is going to be a huge f…. deal,” he wrote.

So far, automation has disproportionately affected routine occupations, University of British Columbia economist Henry Siu noted this month during a White House AI workshop in New York. “Those are occupations that perform a narrow set of rule-based and repetitive tasks,” he said. That category takes in middle-class workers ranging from machine operators to travel agents to administrative assistants.

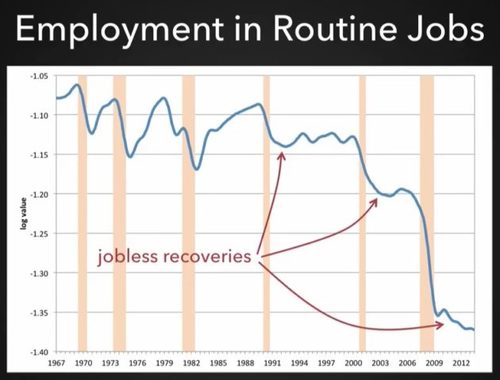

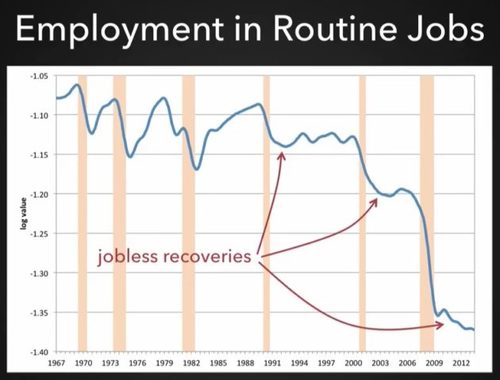

Historically, employment in routine jobs has bounced back after recessions. But the past three recessions and recoveries have shown significant declines in routine jobs, which makes for “jobless recoveries.” (Credit: Jaimovich and Siu, 2015, via Artificial Intelligence Now)

In the years ahead, artificial intelligence is likely to bring automation’s disruptive impact to less routine occupations, Siu said.

“It’s obviously hard to predict, but its effects will likely move away from routine jobs and push towards more complex jobs, in fields like journalism … and medicine,” he said. “But what’s true about complex jobs is that they typically involve a richer variety of tasks. And many of those tasks, AI, in the near term, cannot do.”

Workers in complex jobs also tend to have more education, and more adaptability to find employment in other fields if they’re displaced, Siu said.

The developing trends in employment could worsen the rift between folks who are perceived as the working class vs. the educated elite — a situation that’s unlikely to be remedied by building a wall, or curbing immigration, or bringing manufacturing operations back to the U.S. from abroad.

Vardi acknowledged that automation isn’t the only factor reshaping the workplace.

“Automation is interacting with other major societal forces, such as immigration and societal aging,” Vardi told GeekWire. “One reason that China is putting a major focus on automation is that they expect their workforce to shrink. Also, if there is more competition for low-skill jobs, that may discourage immigration.”

The combined effect could mean that half of the world’s population will be out of the labor force by the year 2050, Vardi said.

That’s not as much of a stretch as it sounds. The U.S. civilian labor force participation rate — which includes discouraged and disabled workers as well as working-age Americans who just don’t want a job — is currently at 62.7 percent. (The distinction between the unemployment rate and the labor force participation rate has already stirred up a statistical kerfuffle in the presidential campaign.)

So if automation looms so large as a factor affecting future employment, surely Clinton and Trump are including the issue on their policy agendas, right?

“Sadly not,” Vardi said, “but [President Barack] Obama has been talking about the impact of globalization and automation, and the need to rethink the social compact.”

Over the past couple of months, the White House’s Office of Science and Technology Policy has helped organize a series of workshops on the anticipated social impact of artificial intelligence. It’s expected to issue a policy report and a strategic plan for AI research and development before Obama leaves office.

Job training programs represent one strategy to address the challenge, although they’re not typically cast as a response to workplace automation. Clinton would expand tax credits to encourage worker training and apprenticeships, while Trump would increase funding for job training for veterans.

The most talked-about concept is something that may be too radical for either Trump or Clinton: setting a wage floor for all U.S. citizens. Such a system would widen the safety net in a world where fewer human workers are needed — setting the stage for the world of work portrayed in “The Jetsons.”

Several countries have been looking at the concept, which is known as universal basic income (UBI) or guaranteed minimum income (GMI).

You could argue that Alaskans have benefited from a basic-income plan for decades, in the form of the Alaska Permanent Fund Dividend. Last month, Swiss voters rejected a UBI proposal to pay out the equivalent of $2,555 per month to every adult, and $644 for each child. Meanwhile, pilot projects are under consideration in Finland, the Netherlands and Canada.

Charles Murray of the American Enterprise Institute is proposing a universal basic income plan that would take the place of America’s current welfare programs, as well as Social Security, Medicare and farm subsidies. Even though the American Enterprise Institute leans toward free enterprise and laissez-faire economics, Murray and other conservatives argue that automation’s rapid rise will force us to rethink our approach to work and compensation.

“It will need to be possible, within a few decades, for a life well lived in the U.S. not to involve a job as traditionally defined,” Murray wrote in The Wall Street Journal last month. “A UBI will be an essential part of the transition to that unprecedented world.”

It may turn out that whole new classes of jobs will arise to replace the occupations that robots and AI agents will fill. “Every time technology disrupts a job, a new set of jobs is created,” Seattle-area entrepreneur Naveen Jain observed.

Humans are likely to be in charge of designing new generations of intelligent devices, coming up with creative ways to use them, and keeping them in working order. Moreover, AI assistants could help displaced factory workers and truck drivers reinvent themselves as artists, caregivers or coders.

But even if the next generation is in for a work-free utopia rather than a robo-apocalypse, it’s high time for policymakers and programmers to address how the automation revolution can work for us — instead of against us.