George Floyd, Homicides, And The 22nd Paragraph Effect

By Steve Sailer

06/02/2021

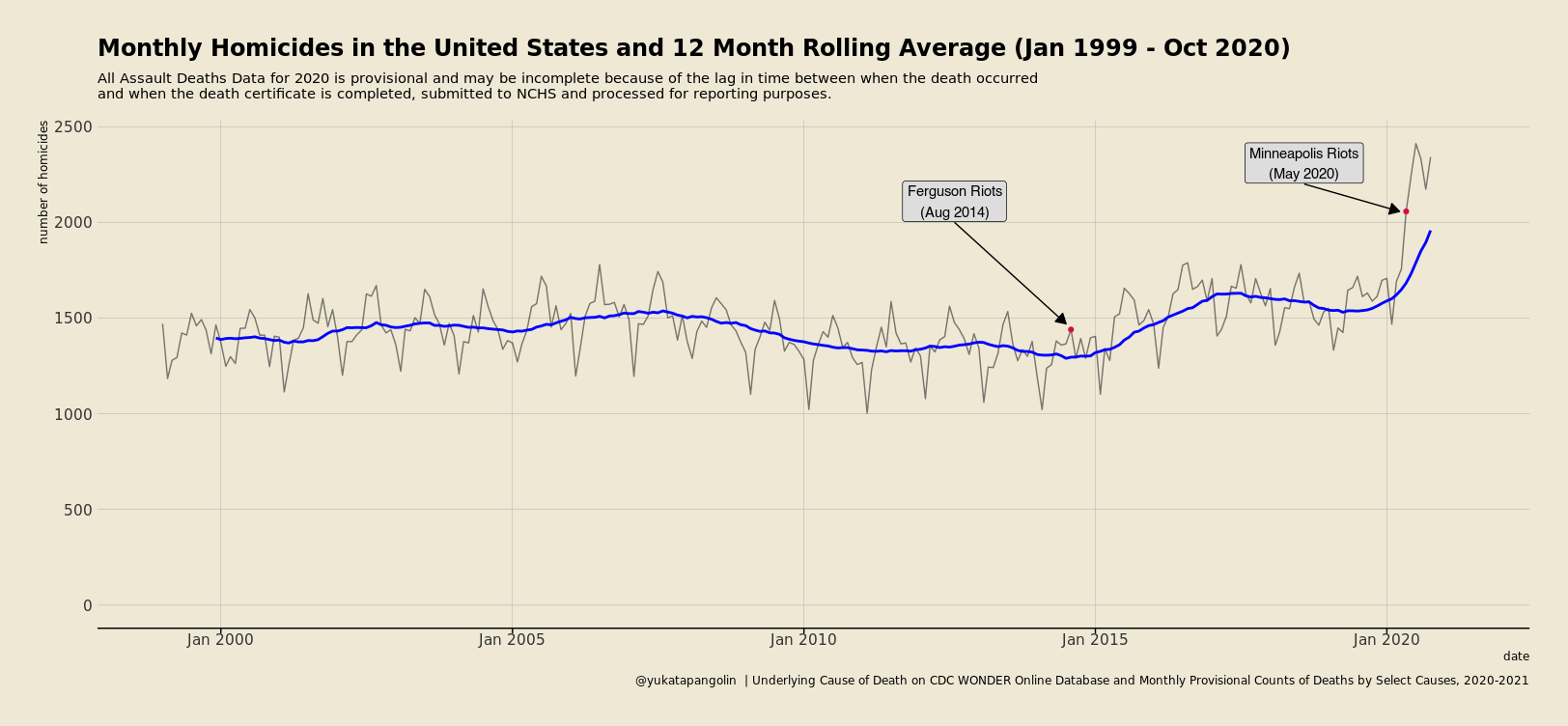

This is from Forest Dweller. The CDC counts deaths by homicide by month, with a huge increase from May onward (jagged gray line). The smoothed blue line is a 12 month running average.

In The New York Times news section, Neil MacFarquhar shows how to talk about the Murder Surge without mentioning the Racial Reckoning until the 22nd paragraph:

With Homicides Rising, Cities Brace for a Violent Summer

Homicide rates in large cities were up more than 30 percent on average last year, and up another 24 percent for the beginning of this year, according to criminologists.

By Neil MacFarquhar

June 1, 2021, 5:25 p.m. ETThe upbeat mood at an album release party at El Mula Banquet Hall in Miami-Dade County was shattered when three men in ski masks jumped out of a stolen white Nissan S.U.V. and fired randomly into the crowd early Sunday.

A white Nissan S.U.V., ladies and gentlemen. Whiteness continues to run amok.

Some revelers fired back. The whole encounter unrolled in about 10 seconds, leaving two people dead and 21 others injured. It was one of the worst shootings in the Miami area in recent memory, and came just a day after one person died and six were wounded in a drive-by shooting in another part of the city.

Memorial Day weekend typically kicks off a three-month summer season for violent crime, and in the past few days there were also homicides at a nightclub in Dallas, on a freeway in Detroit and in an apartment building in Baton Rouge, La., where a 1-year-old was among the three people killed.

With the pandemic precautions that kept people at home receding, officials and police departments are bracing for a violent summer. “We are seeing an uptick in violent crime across the country, specifically gun violence,” Daniella Levine Cava, the mayor of Miami-Dade County, said. “People have been cooped up, they have been psychologically affected by this pandemic.”

The question now is whether the rising level of killings in American cities that began last year, as the pandemic wrought economic and social hardship, will continue to climb.

The F.B.I. does not release full statistics until September, but homicide rates in large cities were up more than 30 percent on average last year, and up another 24 percent for the beginning of this year, according to criminologists.

In some places, …

The drop …

Superintendent David Brown …

Given the high numbers in 2020, no rapid decrease should be anticipated this year — the hangover from any significant crime wave continues after the peak is reached, the police and criminologists said.

“Even though the pandemic is receding, it casts a really long shadow, along with the social unrest related to policing,” said Max Kapustin, an assistant professor of economics and public policy at Cornell University who studies crime.

Overall crime figures were down during the coronavirus pandemic. Rape, robbery and petty thefts — which constitute the vast bulk of the numbers — tend to be crimes of opportunity, and with people staying home and businesses shuttered, there were far fewer chances. Those numbers should rebound as life across the United States returns to more normal patterns, analysts said.

Homicides were a notable exception, however, with almost every major city in the United States seeing large increases in 2020. In Chicago and several other cities, last year was the worst year for killings since the mid-1990s.

Homicides in Portland, Ore., rose to 53 from 29, up more than 82 percent; in Minneapolis, they grew to 79 from 46, up almost 72 percent; and in Los Angeles the number increased to 351 from 258, a 36 percent climb, according to statistics analyzed by Jeff Asher, a former crime analyst for the New Orleans Police Department.

Those increases have continued in many cities this year.

Homicides in Philadelphia are up almost 28 percent, with 170 through May 9, compared with 133 in the same period last year; in Tucson, Ariz., the number jumped to 30 from 17 through May 13, an increase of 76 percent.

In New York …

Analysts are still pondering exactly why.

Trying to ascribe reasons for a crime wave is often a puzzle, but the pandemic is considered an important contributing factor to the elevated homicide rates. It created economic turmoil and widespread unemployment as well as other side effects like leaving domestic abuse victims trapped at home.

Well, what happened to domestic homicides?

Police departments in New York and Detroit saw occasional periods of fewer officers on the streets when Covid-19 outbreaks forced significant numbers to isolate or quarantine.

Guns contributed to the equation as well. “Were it not for the proliferation of firearms through our society and in our big cities, we would not have seen these big jumps in homicide,” said Richard Rosenfeld, a criminologist at the University of Missouri in St. Louis.

Homicide rates, already ticking up in the few months after March 2020 when the pandemic began, exploded last summer. This is partly because of what criminologists refer to as the “seasonal effect,” the habitual rise in crime during the warm months in northern cities, starting with Memorial Day.

And, oh, yeah, something else happened on Memorial Day 2020, which, this being the 22nd paragraph probably only 1% of NYT readers are going to get this far:

Another significant factor was the unrest following the murder of George Floyd by a Minneapolis police officer, which prompted a wave of protests in more than 140 cities across the United States.

The year before Mr. Floyd’s death — from May 25, 2019, to May 25, 2020 — there were 2,885 shootings in Chicago that resulted in 521 deaths. From May 25, 2020, to May 25, 2021, there were 818 deaths from 4,562 shootings, an increase of almost 60 percent in both categories, according to Christopher Herrmann, a professor of law and police science at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice.

In the aftermath, some criminologists attributed the spike in homicides to hesitancy among residents to turn to the police for help. Others argued that it was the police who held back. The debate, frequent after any crime wave, remains unresolved.

“When police legitimacy is greatly reduced, you get more crime because people are no longer relying on the criminal justice system for assistance,” Dr. Rosenfeld said. “People are less willing to cooperate with police in investigations, less willing to report crimes or other problems to the police and more willing to take matters into their own hands.”

Some police officials said the outlook for addressing violent crime appeared bleak, especially with no bipartisan effort to reduce crime or gun violence materializing. “I am very sad to say that this summer is going to be a long summer for the American people,” Art Acevedo, the Miami police chief, said on CBS’s “Face the Nation” on Sunday.

The lingering question is whether 2020 and its aftermath will prove to be an outlier, with the toll receding toward the record lows seen around 2013 or stopping somewhere higher than it was before the pandemic.

Wait, what happened after the relatively non-lethal year of 2013? … Oh, yeah, Ferguson and Black Lives Matter.