Glenn Burke: The Great Gay Hope Who Couldn’t Actually Hit The Ball

By Steve Sailer

06/03/2022

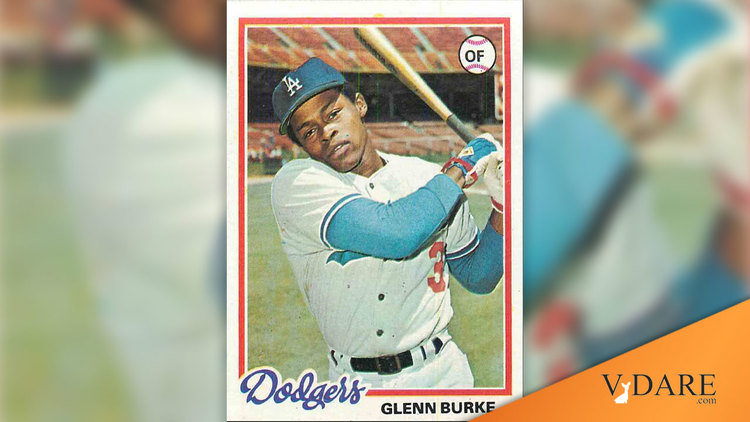

It’s Pride Month so sportscasters are writing their annual Narrative about the career of the first “openly gay” major league baseball player Glenn Burke and how the Los Angeles Dodgers homophobically ran him out of town in 1978. I’m going to do my definitive (and hopefully last) debunking of this old trope by looking at the, you know, baseball statistics. From The New York Times sports section:

The Dodgers Embrace the Family of a Player They Once Shunned

At Pride Night, Los Angeles will celebrate the life of Glenn Burke, M.L.B.’s first openly gay player. His family will be there hoping the honor makes Burke “partially whole.”

By Scott Miller

June 2, 2022

LOS ANGELES — The life and times of Glenn Burke are too big to squeeze into one night, but the Los Angeles Dodgers are finally giving it their best shot. In staging their ninth annual LGBTQ+ Pride Night, they will celebrate their former outfielder — and the first major leaguer to have come out as gay — on Friday during their series with the Mets.

Call it closing the circle 44 years later. Call it righting a wrong after they drove him out of town in 1978.

… Burke played big and lived bigger, his time in Los Angeles brief but his imprint lasting.

No, he played small. I can remember listening to Vin Scully broadcast Dodger games in the 1970s and my heart dropping whenever he said Glenn Burke was coming to the plate. Burke was a rally killer, a big fast guy with no power and no ability to get a walk. He wasn’t even a good defensive outfielder. He was a classic Looks Good In a Uniform But Can’t Play type, as both my memory of listening to a lot of games and modern statistics show:

Teammates adored the outfielder with outrageous athleticism and an outsized personality. They describe him as a player who could beat you on the baseball field and school you on the basketball court. The athlete and showman who invented the high-five and had a physique that a teammate said could rival even Bo Jackson’s.

… But Burke was also a man so far ahead of his time that the times didn’t — wouldn’t — recognize him. He was traded by the Dodgers, shunned by the Oakland Athletics and, eventually, ostracized from baseball. He wound up lost, alone and alienated. He was briefly homeless and turned to cocaine and crack. He did a short stint in prison for drug possession. He contracted AIDS and died from its complications at 42 in May 1995.

It’s almost as if Glenn Burke wasn’t a really good decision maker, which might have had something to do with his failure to capitalize on his athletic gifts…

That’s where the story could have ended. But today, the credits continue to roll.

Burke made his debut with the Dodgers in 1976 and mostly backed up their great outfield of that era — Baker, Reggie Smith and [Rick] Monday. In the 1977 World Series, between the Dodgers and the Yankees, he started Game 1 in center field while Monday nursed a sore back.

Only seven months later, the Dodgers shipped him to Oakland in a trade for Bill North. It was a baffling, mid-May deal that didn’t add up unless you knew about Burke’s personal life.

No. The Dodgers trading the terrible 25-year-old Glenn Burke for adequate veteran centerfield Bill North was a terrific move that helped the Dodgers edge out Cincinnati’s aging but still formidable Big Red Machine by 2.5 games.

The Dodgers in 1978 had a super stable infield of Steve Garvey, Davey Lopes, Bill Russell and Ron Cey (who went to four World Series together from 1974-1981) and they had a bunch of veterans who could hit and maybe play some outfield: Reggie Smith in right, Dusty Baker in left, and 32-year-old Rick Monday (who’d been a centerfielder, but now was too old to cover the territory), Lee Lacy, and Joe Ferguson. But they needed a centerfielder.

From looking at him, you might think third-year player Glenn Burke could fill that role. But they’d given him 219 at-bats in 1977 and he had an okay sounding .254 batting average, but only a .280 on-base percentage and a .320 slugging average, making him 38% worse than the average National League hitter, pitchers included. And in 1977 he was a bad outfielder, too, being defensively -0.9 wins worse than average (i.e., costing them one win with his glove vs. a normal outfielder).

In 1978, he started off even worse. By May 17, 1978 the Dodgers had only given him 19 plate appearances and he had 4 singles, no extra-base hits, and no walks, only 19% as good as the average NL hitter of 1978. Clearly, Burke wasn’t going to be the solution to the Dodgers’ centerfield problem.

So they traded him to the Oakland A’s for 30-year-old Bill North, who was hitting at 85% of the AL average. North played in 110 games, almost all in center for the Dodgers, and produced at 82% of the NL average offensively (mostly due to getting a lot of walks for a singles hitter).

In terms of Wins Above Replacement, which tries to estimate the total offensive and defensive contribution a player makes to winning ball clubs relative to a “replacement player” — the kind of forgettable player you can always scrounge up from the minors or off the waiver wire — at the time of the trade in May, North had +0.6 WAR and Burke -0.2. With their new teams, they both continued at the same pace: in the remaining 3/4ths of the season, North was +1.8 WAR for the Dodgers and Burke was -0.6 for the A’s. So, if the Dodgers had decided not to make the trade, Burke would likely have cost them, relative to North, an additional 2.4 wins, or their 2.5 game margin over the Reds in the NL West division race to make the playoffs.

The A’s brought Burke back in 1979 and he was terrible again and that was his last season.

The point is that it’s easy for journalists to look up Burke’s statistics and realize that the whole Narrative is inflated. But they don’t because it’s Pride Month.