By Steve Sailer

09/05/2011

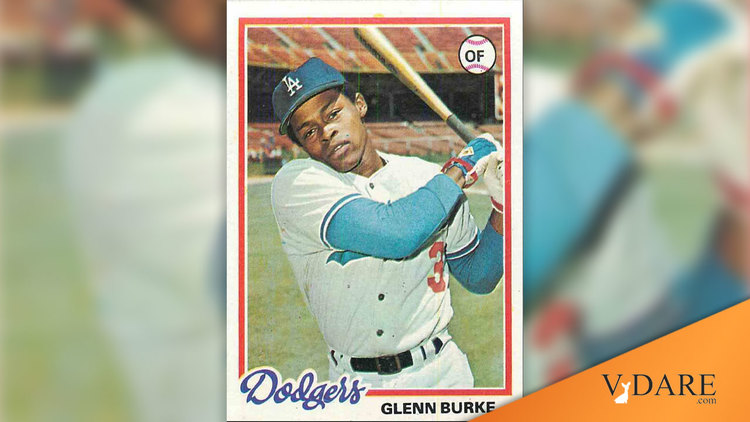

From ESPN.com, about Glenn Burke, a 1970s ballplayer who died of AIDS:

What most people didn’t know was that Burke was gay. Following his retirement, in 1980, he became the first major leaguer to come out. Even though he tried to keep his sexuality a secret during his playing days, there had been rumors in the clubhouse. And as the 2010 television documentary Out: The Glenn Burke Story revealed, Dodgers executives scrambled to squash those rumors at all costs: In the off-season of 1977, team VP Al Campanis offered Burke $75,000 to get married. According to a friend, Burke rejected the marriage deal with a mix of wit and rebelliousness. He told Campanis, "I guess you mean to a woman."It was around that time that Burke struck up a relationship with Spunky Lasorda, aka Tommy Lasorda Jr. Spunky was a lithe young socialite who frequented West Hollywood’s gay scene, smoking cigarettes from a long holder. A 1992 GQ profile of Spunky portrayed his homosexuality as an open secret. But his father was in staunch denial and remained so even after Spunky’s death, in 1991, from pneumonia. GQ reported that the death certificate said his illness was likely AIDS-related. "My son wasn’t gay. No way," Lasorda Sr. told the magazine.

Burke and Spunky’s relationship didn’t become public until years later and remains ambiguous. Burke’s sister, Lutha Davis, insists the two men were just close friends. In his 1995 memoir, Out at Home, co-authored with Erik Sherman, Burke went out of his way to leave the true nature of the relationship unclear. "That’s my business," he wrote. He also explained that Lasorda Sr.’s homophobia was something he and Spunky commiserated about. Burke described them turning up together at Lasorda’s house one night, done up in pigtails and drag, hoping to stage a kind of gay Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner. They chickened out before knocking on the door.Whatever the case, Burke’s association with Spunky marks the point at which his big league career took an irrevocable left turn. Lasorda stopped being amused by the player’s dugout antics and, according to Burke, turned on him. "Glenn had such an abundance of respect and love for Tommy Lasorda," says Burke’s sister. "When things went bad at the end, it was almost like a father turning his back on his son." Early in the 1978 season, the Dodgers abruptly dealt Burke to the Oakland A’s — among the most lackluster teams in baseball — for Billy North, an outfielder past his prime. L.A. sportswriters described the trade as sucking the life out of the Dodgers' clubhouse. A couple of players were seen crying at their lockers.

For Burke the trade had everything to do with his sexuality — though the outfielder sounded off to the press about it in only the most cryptic terms. "I never got a chance here," he said. "I felt I was supposed to kiss ass and I didn’t."After unproductive years in 1978 and '79, Burke hoped for a fresh start in 1980 under new A’s manager Billy Martin. But the gay rumors followed Burke to Oakland. Martin threw the word "faggot" around the clubhouse and didn’t play Burke. Some teammates even avoided showering with him. Burke, accustomed to being the heart of the clubhouse, felt crippled by the discomfort he was causing. His unhappiness was compounded by a knee injury and a demotion to Triple-A. After playing just 25 games in the minors in 1980, he abruptly retired. He was 27 years old. "It’s the first thing in my life I ever backed down from," he later said.

Burke started hanging around San Francisco’s Castro district. He became a star shortstop in a local gay softball league and dominated in the Gay Softball World Series. "I was making money playing ball and not having any fun," he said of his time in the majors. "Now I’m not making money, but I’m having fun." Jack McGowan, a friend in the Castro who has since passed away, once said of Burke: "He was a hero to us. He was athletic, clean-cut, masculine. He was everything that we wanted to prove to the world that we could be."

In the Castro, Burke’s creation of the high five was part of his Herculean mystique. He would flash his magnetic smile and high-five everyone who walked by. In 1982, he came out publicly in an Inside Sports magazine profile called "The Double Life of a Gay Dodger." The writer, a gay activist named Michael J. Smith, appropriated the high five as a defiant symbol of gay pride. Rising from the wreckage of Burke’s aborted baseball career, Smith wrote, was "a legacy of two men’s hands touching, high above their heads."

By that time, however, Burke was struggling with a drug habit. It escalated in 1987, when a car plowed into him as he was crossing a street, breaking his right leg in four places and stealing his athleticism. He couldn’t hold a job. He went broke. He did some time at San Quentin for grand theft. Then, in 1993, he tested positive for HIV. He passed away on May 30, 1995, after a sharp and grisly decline.

I remember Glenn Burke from when I was an intense Dodger fan in the late 1970s. He struck me then as a useless waste of space any time he got into the lineup. Looking up his statistics, I see I was right: In his career, he had 556 plate appearance, or about one full season’s worth. His career stats in MVP form were .237 average, 2 homers, and 38 rbi. He got all of 22 walks in his career. His career on base percentage was .270 and slugging average was .291, for an OPS of .561. His OPS+ on a scale where an average big leaguer is 100 was 57. His career wins above replacement was -3.1, evenly split by being terrible on both offense and defense. The remarkable thing about Burke was not that his promising career was sidetracked by irrational discrimination, but they let him stay in the big leagues so long when there were better players in Triple A.