By Steve Sailer

09/09/2022

City Journal runs an article I’ve long been looking forward to: exactly how suburban Oak Park, Illinois (where my father grew up) managed to avoid getting destroyed by tipping from all white to all black like Oak Park’s neighbor, the Austin neighborhood of Chicago (where my wife grew up).

In Austin in the late 1960s, unscrupulous realtors went for the Quick Killing of flipping the whole place from white to black, pocketing commissions on every house on a block in a couple of years, and often two sales: white to middle class black to underclass black. (Of course, they drove down property values so much that they must have paid some kind of price for ruining their neighborhood in the long run, but they made the Big Score in the short run.)

So, Oak Park took a number of steps to rein in realtors, many of them sensible but likely illegal. And managed to stabilize the demographics of Oak Park for the last several decades. What’s interesting is that all the social engineering is still going on to maintain that stability.

Chicago suburb Oak Park’s effort to achieve racial balance counsels skepticism about engineered diversity.

William Voegeli

Summer 2022 The Social Order… One of the most durable and, by its own standards, successful efforts to achieve a stable integrated community can be found in Oak Park, Illinois, a suburb of some 55,000 residents abutting Chicago’s border, eight miles west of the Loop. Oak Park was 99 percent white in 1970, but blacks accounted for 11 percent of its residents in 1980 and 18.5 percent by 1990. Based on the pattern established in many other Chicago neighborhoods and suburbs, as well as in communities across the country, Oak Park should have been poised for “white flight,” as the black population’s growth reached a “tipping point” that saw the slow departure of whites turn into a rush for the exits. Instead, Oak Park’s demographics have changed only slightly. In 2021, the village’s population was 18.4 percent black. (As such, it satisfies Rothstein’s criterion for integration, since African-Americans account for 16.7 percent of metropolitan Chicago’s population.) The modest decline in Oak Park’s white population, from 76.9 percent in 1990 to 66.1 percent in 2021, corresponds to a rising number of Hispanic and Asian residents.

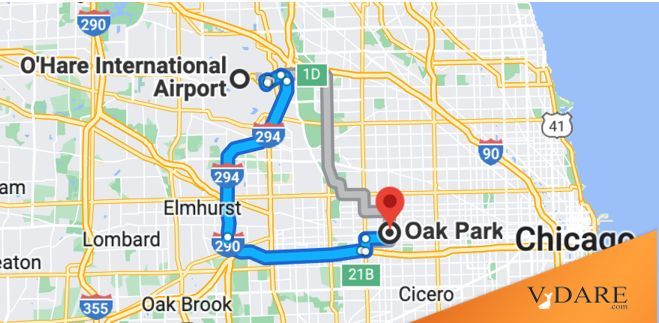

To achieve this degree of integration and then sustain it for decades is as unusual in northeastern Illinois as it is throughout the United States. You won’t find it anywhere in Oak Park’s immediate vicinity, which is made up of other communities that were also nearly all-white for most of the twentieth century. An adjacent village, River Forest, remains 83 percent white and 7 percent black. Cicero and Berwyn, to Oak Park’s south, are now predominantly Hispanic, with small minorities of non-Hispanic whites and even smaller ones of non-Hispanic blacks. Just west of Oak Park, Maywood and Bellwood have large African-American majorities, as does Austin, the Chicago neighborhood immediately east of Oak Park, which is 84 percent black and 4 percent white.

Austin’s transformation from middle-class and predominantly white (more than 99 percent white in 1960) to poor and predominantly black (over 86 percent black in 1990) was the proximate cause of Oak Park’s decision to confront and control its demographic change. “Reconsidering the Oak Park Strategy,” an academic paper written in 2002 by Evan McKenzie, a political scientist, and Jay Ruby, an anthropologist, states: “The 1970s witnessed classic block-by-block resegregation in Austin, an event that had enormous psychological impact on Oak Parkers.” As a result, “Austin became a negative example for many Oak Parkers, who were determined to chart a different course.”

That course became “managed integration,” also known as “integration maintenance” or “intentional integration.” The policy was carried out by the village government, advisory boards, civic groups, and, above all, the nonprofit Oak Park Regional Housing Center (OPRHC), created in 1972. The goal was to assist people seeking to move into Oak Park, especially blacks, while reassuring those thinking about leaving Oak Park, especially whites.

Beyond stabilizing Oak Park’s demographic profile to resemble closely that of the Chicago metropolitan area, the managed integration program worked to prevent the emergence of any predominantly black or white neighborhoods within the suburb. As J. Robert Breymaier, executive director of OPRHC from 2006 to 2018, has written, the goal is to encourage as many relocations as possible that will “sustain or improve the integration of a particular building or block.” McKenzie and Ruby observed that 81 percent of Oak Park’s blocks had at least one black family in 2000. This is, they say, “an achievement that few communities have realized.” It is also, however, an effort consistent with writer Steve Sailer’s derisive opinion that managed integration amounts to making sure that there is “one black per block” but as few as possible in excess of that.

I wouldn’t say my opinion of Oak Park’s black-a-block racial quota was derisive. I concluded, “I can recall reading about Oak Park’s “black-a-block” quota in a newsmagazine, probably Newsweek in 1988. As a young idealist, I was totally against racial discrimination. Yet, having taken my father and uncle to visit their boyhood home, driving through the endless desolation of un-quotaed Austin only to suddenly arrive in suburban paradise as imagined by F.L. Wright in Oak Park … well, maybe there are worse things than racial quotas …”

I wouldn’t say my opinion of Oak Park’s black-a-block racial quota was derisive. I concluded, “I can recall reading about Oak Park’s “black-a-block” quota in a newsmagazine, probably Newsweek in 1988. As a young idealist, I was totally against racial discrimination. Yet, having taken my father and uncle to visit their boyhood home, driving through the endless desolation of un-quotaed Austin only to suddenly arrive in suburban paradise as imagined by F.L. Wright in Oak Park … well, maybe there are worse things than racial quotas …”

Initially, Oak Park’s managed integration effort focused on homeowners, seeking simultaneously to encourage “fair housing” — a nondiscriminatory real-estate market — and discourage white flight. To keep the sight of For Sale signs on lawns from triggering panic selling, as had occurred in Austin and other Chicago neighborhoods, Oak Park prohibited them. A 1977 Supreme Court ruling held that such bans violated the First Amendment, but because no Oak Park real-estate agent has challenged it in court, the prohibition remains in effect as a practical matter.

My conspiracy theory is that Oak Park’s many no doubt illegal policies are almost never challenged in court and seldom even mentioned in the newspapers because The Powers That Be would prefer not to see America’s most architecturally famous suburban housing stock reduced to ruin.

Oak Park also offered, beginning in 1978, the Equity Assurance Program, an insurance policy providing protection from housing-market changes related to integration. In Chicago neighborhoods that had resegregated, either the fact or fear of demographic change had led many homeowners to sell at a loss. The Equity Assurance Program guaranteed policyholders that they would be compensated if they found themselves selling their home at a price below what they paid for it.

Perhaps the best evidence for the success of Oak Park’s effort to stabilize integration is that no claims have ever been made under this insurance program. Instead, property values rose steadily as Oak Park became one of the most affluent suburbs in western Cook County. Breymaier writes that diversity is among Oak Park’s “core values,” central to its “identity and sense of place,” as well as the village’s “brand.” Integration, in this view, is sustained by a virtuous circle: it draws people of all ethnicities who value life in a diverse community, and then gives them a stake in preserving it. The steadily climbing property values, in turn, guarantee that homeowners of any ethnicity are likely to be upper-middle-class professionals with compatible outlooks and concerns.

Oak Park these days is pretty gay, presumably attracted by the fabulous aesthetics.

By the time McKenzie and Ruby examined Oak Park’s managed integration program, nearly 30 years after its inception, it had “become so complicated that few Oak Parkers fully understand it.” There’s nothing esoteric about a crucial element, however. Oak Park is an older inner-ring suburb, unlike those around the country that saw subdivisions of single-family homes spring up in the years after World War II. As a result, it has fewer homeowners and more renters than most suburbs. Breymaier reports that when the managed integration effort began in the 1970s, half of Oak Park’s residential units were rental properties; 40 percent remain so. Most of these rental units are apartments in small buildings, managed by “mom-and-pop” landlords who own, at most, a handful of additional apartment buildings.

The city government has used sticks, such as building inspections and the threat of fines, and carrots, including loans and other financial benefits, to motivate landlords to use OPRHC as their rental agent. Through the city’s Diversity Assurance Program (DAP), for example, owners of apartment buildings can receive low-interest loans to make upgrades in exchange for a five-year commitment to do business with OPRHC. In addition, McKenzie and Ruby write, DAP “pays the owner rent for leaving apartments empty until a tenant of the proper race can be found — i.e., a white tenant for a predominantly black building, or a black tenant for one that is predominantly white.”

Breymaier estimates that OPRHC brokered 40 percent of the leases signed in Oak Park over the five years from 2010 through 2014. OPRHC, in turn, engages in “affirmative escorting” or “reverse steering” when an apartment-seeker contacts it to inquire about vacancies. A 1988 Chicago Reader article on Bobbie Raymond, OPRHC’s founder, described the goal less clinically: for clients to end up in “appropriate apartments.” That is, “whites are usually given listings on the east side of the village, next to Chicago’s mostly black Austin neighborhood.” Blacks, conversely, “are sent to white neighborhoods in the center and west of Oak Park, or referred to other suburbs with newer housing.”

In other words, some blacks are steered clear out of town. Presumably, the OPRHC cherry picks the more desirable blacks for Oak Park. At my old employer, it wasn’t uncommon for black secretaries to rent in Oak Park.

Breymaier calculates that 68 percent of relocations that OPRHC facilitates are “affirmative moves” — ones that increase a block’s or a building’s racial integration. By his estimation, only 25 percent of relocations taking place on the open market, without OPRHC involvement, are affirmative moves.

Managed integration operates in a gray area. As Breymaier carefully stipulates, “Landlords do not have the same legal ability to engage in integration activity that the nonprofit and property-free Housing Center enjoys.” Translated, this means that an Oak Park landlord would invite endless trouble by rejecting an application from a tenant of the “wrong” racial or ethnic group. OPRHC, by contrast, has spent 50 years telling clients, based on their race, that they should consider this neighborhood rather than that one, and has done so without incurring lawsuits or bad publicity. “It is through direct, face-to-face conversation that OPRHC addresses irrational fears, provides missing information, replaces myths and stereotypes with facts, and engages in gentle persuasion to consider new options,” in Breymaier’s account of the coaching process. “This results in a much different housing search than would occur without OPRHC.”

Its long-term success in stabilizing integration makes Oak Park an exception. But what rule does it prove? It’s clear to Breymaier that, because managed integration has bequeathed “strong and stable property values” and “a foundation for community harmony,” Oak Park has “provided a replicable model for other communities.”

If this is true, why have only a few other places tried the Oak Park strategy, and why has none replicated its success?