By Steve Sailer

03/26/2021

Oh, yeah, well, my mom was that really racist white woman portrayed in Spike Lee’s BlacKkKlansman and in 1981 she massacred 40 Tibetan monks in a Colorado Springs lamasery with just a set of corncob skewers.

Try to top that!

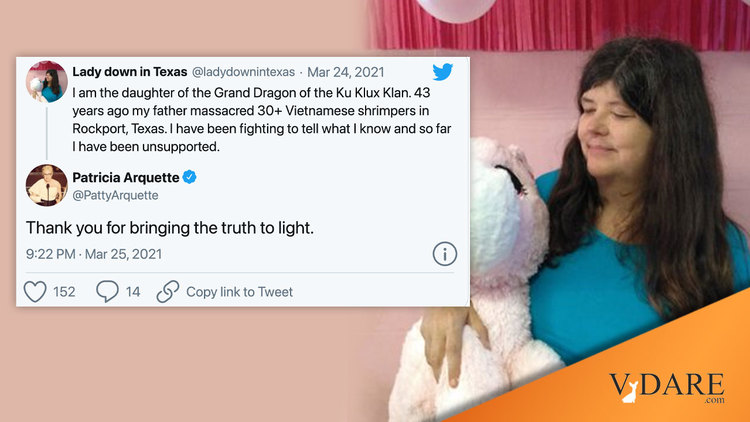

Judging from the comments on Twitter, a large fraction of Americans today automatically believe these kinds of Hate YT tall tales.

Personally, I can recall reading many times about this long-running struggle between Texas shrimp fishermen, who understood the ecological limits of their fishing grounds, and Vietnamese refugee fishermen who did not. The story was so well known it was made into Louis Malle’s 1985 movie Alamo Bay, starring Ed Harris and Amy Madigan.

The only killing on record is one American fisherman, Billie Joe Aplin, being gunned down by some Vietnamese, who were eventually acquitted on self-defense.

Besides massacring all those Vietnamese and Mexicans, her dad, the KKK Grand Dragon, once borrowed my cousin’s Chevy. When he brought it back, it was all dinged up but he refused to pay for the body shop bill.

The man is a MONSTER.

Seriously, the true story of the clash between native and newcomer shrimpers in Texas, while less like a scene from John Wick 4 is of intellectual interest. It’s an example of Garrett Hardin’s concept of the Tragedy of the Commons. Elinor Ostrom became the first female winner of the quasi-Nobel Prize in Economics in 2009 for her work on how fishing communities work out local customs to keep from wiping out near-shore fishing grounds. In my review of Jared Diamond’s 2005 book “Collapse,” I worked through the logic:

Diamond notes that there are three possible solutions to what Garrett Hardin called “the tragedy of the commons,” or the tendency for individuals to over-consume resources and under-invest in responsibilities held in common, leading to ecological collapse.

- Government diktat.

- Privatization and property rights — but that’s impractical with some resources, such as fish.

- “The remaining solution to the tragedy of the commons is for the consumers to recognize their common interests and to design, obey, and enforce prudent harvesting quotas themselves. That is likely to happen only if a whole series of conditions is met: the consumers form a homogeneous group; they have learned to trust and communicate with each other; they expect to share a common future and to pass on the resource to their heirs; they are capable of and permitted to organize and police themselves; and the boundaries of the resource and of its pool of consumers are well defined.”

A classic supporting case that that Diamond doesn’t bring up: American shrimp fishermen in Texas were universally denounced as racists in the late 1970s when they resisted the government’s efforts to encourage Vietnamese refugees to become shrimpers in their waters. French director Louis Malle made a movie, Alamo Bay, denouncing ugly Americans fighting hardworking immigrants.

What got lost in all the tsk-tsking is that fishing communities always resist newcomers, especially hardworking ones, because of the sizable chance that the outsiders who don’t know the local rules or don’t care about them will ruin the ecological balance and wipe out the stocks of fish.

The evidence Diamond assembles indicates, although of course he never dares to state it bluntly, that the fundamental requirement for dealing effectively with environmental danger is: start with a population that’s limited in number, cohesive, educated, and affluent.

Needless to say, mass immigration from the Third World works against all those characteristics.

For example, the Washington Post reported on the shrimp wars in 1984 in the classic upside down manner. If you keep reading, the story gets more interesting as it progresses from a simple tale of white racism to a complex story about immigrants disrupting sustainable environmentalism.

Vietnamese Shrimpers Alter Texas Gulf Towns

By Paul Taylor December 26, 1984

“The Vietnamese shrimper is one tough competitor. He’s rugged. He don’t listen to the weatherman or go by any work schedule. He’s out there day and night, dragging the bay.

“And the SOB, he can live on practically nothing.”

Emery Waite, shrimp wholesaler, popped open another late-afternoon light beer and motioned toward the shrimp boats docked outside his office window.

“There are 150 boats in the harbor,” he said. “Maybe 25 are still owned by Americans. Same way with the shrimp houses. We got 11 in Seabrook. Eight are owned by Vietnamese, three by Americans.”

“And,” he added, “mine’s up for sale.” …

“They ain’t beating us with brains,” Waite shot back. “They’re beating us with a lifestyle. They live eight or 10 in a trailer and eat only what they catch. How do you compete with that?” …

Several of the Vietnamese boats were burned, and there were one or two instances of gunplay out on the water as the Vietnamese fishermen kept breaking all the “rules of the road” that govern how long shrimpers are supposed to stay on the bay and who gets priority to fish in which sections. (They broke them, of course, because they were ignorant of them.)

The Ku Klux Klan became active in the area. “I promise them a lot better fight here then they got from the Viet Cong,” vowed Louis Beam, the Texas Grand Dragon, in 1981.

The hostilities resulted in the shooting of an American fisherman by two Vietnamese shrimpers in Seadrift, a community 50 miles down the bay. The two claimed self-defense and were acquitted. (The incident is the basis for a Louis Malle movie, “Alamo Bay,” due out next year.)

In time, peace was restored with the help of a U.S. District Court restraining order against Klan activity.

… The Vietnamese fishermen’s only gripe is that the American shrimpers won’t let them work in the Houston Ship Channel, where catches are usually plentiful. “A Vietnamese tries to go in there,” Khanh said, “and he’ll get his boat sunk.”

The Americans say the Vietnamese don’t work the channel because they lack the skills. It is crowded and treacherous — a mine field of sunken wrecks, enormous oil tankers and tug boat operators who don’t think twice about ramming little 35-foot shrimp boats that get in their way. “If they ever tried working the channel, they’d rip their nets in about five minutes,” said Derek Stout, 38, a lifelong shrimper.

The Americans, for their part, grudgingly concede that the Vietnamese work hard, but they consider them rotten competitors. “At the dock, they think nothing of pulling up alongside your boats and unloading their catch right across your deck,” said Reynolds.

“Out on the water, if you see a shrimp boat circling around, you pretty well know it’s because he’s found something he wants to go back and get. It’s always been considered bad form to help yourself to what he’s discovered. But once the Vietnamese came onto the bay, you’d have a dozen boats right on top of that poor guy in no time.

“It is a collection of small irritants, but they add up. It’s not so much racial prejudice that makes people here resent the Vietnamese, it’s more like a culture clash.”

Perhaps more importantly, the natives also resent the Vietnamese for overworking the bay. Catches have been down by 50 percent or more in the past several years. “There are only so many shrimp out there,” said Stout. “You bring more boats in, each one gets less. Plus the overall harvest goes down, because the constant dragging doesn’t leave the shrimp with any chance to grow.” …