By Steve Sailer

07/20/2021

The New York Times runs an insanely in-depth analysis of the 1.7 million pitches thrown in the major leagues since 2017 by three of its baseball-crazed staffers to measure the effects of umpires starting to crack down on June 3 of the increased use of super-sticky glue by pitchers to increase the spin rates of their pitches.

The Pitchers Whose Spin Rates Fell Most After a Crackdown on Sticky Substances

By Josh Katz, Kevin Quealy and Tyler Kepner, July 19, 2021

In the comments, an NYT reader asks why the newspaper doesn’t devote this much brilliant attention to more substantive matters like gun violence and public school test scores.

To be fair, sometimes it does, such as its 2016 article that investigated all 358 mass shootings in 2015 and found that in almost three-fourths, the victims and perps were black. But few subscribers were much interested in hearing that back then, and such a finding would probably get you canceled in 2021.

So, for Bill James–like analysis of important social issues you need to come to iSteve and similar obscure sites, while baseball statistics remain the Safe Space for smart white guys at The New York Times to exercise their natural curiosity and pattern recognition skills.

To summarize the article, yes, umpires finally broadening enforcement of the rule against applying foreign substances to the baseball from just slippery stuff (the spitball) to also include sticky stuff has lowered the spin rates of 102 of the top 131 pitchers, a four percent overall drop in spin rates, and boosted batting. A four percent decline in spin rate translates into one inch less movement, which is the difference on a fastball between, say, a lazy fly ball and a hit. Since June 3, strikeouts have dropped from 24.2% of plate appearances to 23.0%, which is a step in the right direction of getting more action back into baseball.

All in all, a good thing since in April and May pitchers were getting the upper hand, throwing a record pace of no-hitters, and turning baseball into a boring game of strikeouts and occasional homers.

Of the top 10 pitchers whose spin rates have fallen the most since June 3, the three biggest names are Dodgers Trevor Bauer and Walker Buehler and Yankee Gerrit Cole.

Bauer, a nerd, and Cole, a jock, were archrival teammates at UCLA, and have long been conducting a feud over spin rates (that I wrote about in 2019) that’s strikingly similar to the feud between nerd golfer Bryson DeChambeau and jock golfer Brooks Koepka.

This spin rate scandal (if it’s really a scandal) goes back to 2015, when big league baseball started measuring with radar and publishing online the revolutions per minute of every pitch thrown. The smarter, nastier franchises like the Houston Astros started having their MBAs look at the data, which confirmed that higher spin rates help breaking balls break more and four-seam fastballs stay up.

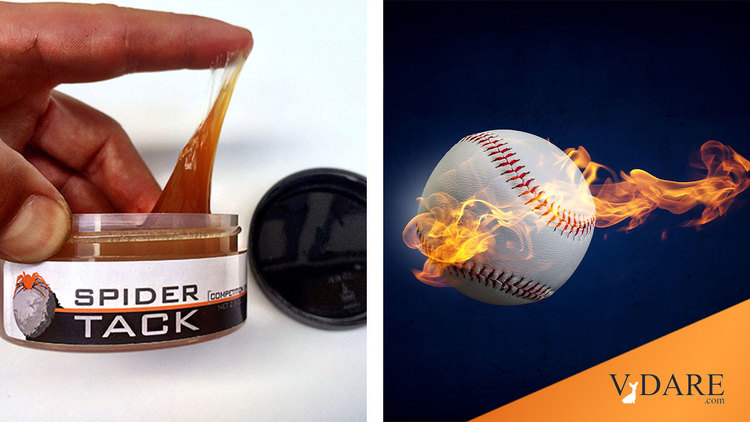

Now everybody sort of knew this already — generating huge amounts of spin with his big hands is how Sandy Koufax dominated in the 1960s with a sailing fastball and a dive-bombing curve. But once you could measure every pitch, teams got to work on doing something about it — a general rule: outside of astronomy, if you can measure something, you can likely figure out a way to manipulate it — which usually involved using ever stickier substances, such as Spider Tack, to get a better grip on the ball.

It appears that Houston identified Cole, then with Pittsburgh, as a major talent who wasn’t maxing out his spin rate, acquired him and persuaded him to do whatever it takes to boost spin, turning Cole into maybe the #2 pitcher in the game behind Jacob DeGrom.

A few years ago, Bauer staged a one-inning science experiment to expose what Houston was doing with Cole, coming out and throwing the first inning of a game with Cole-like spin rates, then, presumably, going back to his normal spin rates in the second inning after, presumably, washing his hands. The nerds who follow Bauer’s Twitter feed figured out instantly what he was signaling, but the MLB didn’t do anything at the time about the stickum trend. So Bauer boosted his spin rates too and won a Cy Young award last year, got a huge contract from the Dodgers, and now, as perhaps tends to happen to athletes with giant contracts, is suspended and being sued for sexual assault by a young lady.

This year, apparently, a sizable majority of pitchers were using stickum, which was making games even more boring. So, the MLB finally did something about it.

Hopefully, the next rule change will be to ban extreme defensive shifts stationing more than two infielders on one side of a line from home plate to second base. Nowadays, left-handed pull hitters (a glamor category in baseball history featuring fan-pleasing names like Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Ted Williams, and Barry Bonds) routinely hit rocket line drives into right field but get thrown out at first by second basemen playing as extra outfielders because the shortstop is playing where the second baseman normally would be. So, why even try to get a base hit, just swing for the fences and hit a homer or strike out?

An interesting ethical question is whether in baseball violating a rule that was not being enforced by the umpires is cheating or not.

In contrast to ballplayers, pro golfers are expected to enforce all written rules on themselves while out on the course. I once saw on TV Arnold Palmer call a penalty on himself for an utterly invisible fraction that pretty much ruined his chance of winning the Senior U.S. Open. Golfers’ relationship with rules officials is cooperative, rather like the French legal system, where the magistrate and attorneys are supposed to work together to arrive at justice.

The relationship between baseball players and umpires is adversarial, rather like the American legal system. It’s the umpires’ job to catch the players if they are cheating. Players are not held to an on-field honor code. For example, if an outfielder traps a line drive a millisecond after it hits the ground for a single, he is supposed, by the traditions of the game, to pretend he caught it on the fly and celebrate his great catch so that the umpire gives him a break.

Which system is better: cooperative or adversarial?

The no foreign substances rule was enforced only on slippery substances, i.e., against the spitball. Sticky substances to get a better grip were considered by hitters and umpires as a way to cut down on beanballs caused by pitches slipping out of the pitcher’s hand. Since hitters compete for salary and playing time against other hitters, there’s no active hitter’s lobby for higher batting average, while hitters do lobby against getting hit in the face by a fastball gone awry. (There’s no mention in this article over whether hit batsman have increased since the ban on stickum.)

But fans tend to like hitting more than pitching. (I’d guess that 5-4 is the ideal score in a ballgame).

But all good things come to an end, and teams like the Astros dedicated to advanced data analytics pushed this way to advantage pitchers to scientific new extremes, which made the game duller.

Have advanced data analytics ever made baseball a better spectator sport? Baseball is now a great game to think about statistically. But to watch?

I’m guessing that improvements in batting order construction have helped score more runs, which fans generally like. Back in the 1960s and 1970s, it was self-defeatingly standard to use your speedy Latin free-swinging base-stealer as your leadoff hitter even though he almost never got on base with a walk. He just looked right, even if he only scored 75 runs per year as your leadoff man.

But I’m not coming up with too many other improvements in the game for spectators wrought by the sabermetrics revolution.

This is a content archive of VDARE.com, which Letitia James forced off of the Internet using lawfare.