By Paul Kersey

08/05/2017

Previously on SBPDL: ‘Worst of the Worst’ (All Black People) Removed From the Streets of Chattanooga; Black Community Comes to Their Defense

Before we begin our journey, let’s consider the facts. Chattanooga, Tennessee is 60 percent white and roughly 33 percent black. For 2016, basically all fatal and nonfatal gun violence in the city was committed by blacks.

A few years ago, the newspaper in Chattanooga tried to quantify the cost of homicide to the city, though it tried to gloss over the race responsible for the bulk of the homicides.

Hint: blacks.

Nothing more than a representation of the black community in Chattanooga, a 60% white city … . where the crime problem is reflected in glaring blackness

Here’s how our friends came up with the data:On average, each murder costs society $17 million, according to a study published in the The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology in 2010. The researchers looked at 654 murder cases and quantified the costs of the victim’s death, the court system, lost productivity and the public’s willingness to pay for crime prevention programs to stop murder.But whom exactly is responsible for this gratuitous waste of resources and capital?By that count, Chattanooga will spend more than $408 million on just 2015’s homicides. For all 119 homicides since 2011, the cost is higher than $2 billion.

Blacks.

The toll in Chattanooga: The Cost Of Chattanooga’s Homicides, Times Free Press, October 18, 2015Every time Satedra Smith pulls into her driveway, her mind goes back to one day a few months ago, when her sons wrestled in the front yard.

That day was a good day.

They were all outside, laughing and enjoying each other as her 20-year-old son roughhoused with his brothers. Every time Smith pulls into her driveway, her mind goes back to that day.

But now it’s a bittersweet memory, because her son, Jordan Clark, is dead — shot to death during a drive-by in Chattanooga on Aug. 25.

In the weeks after he died, she mourned; she went to his funeral; she organized anti-violence rallies, started a foundation in his name, led prayer vigils. But the pain is still fresh.

"It doesn’t seem like it’s been going on two months since it happened," Smith, who lives in Atlanta, said Thursday. "It’s almost like we can still call him and hear his voice. But we can’t."

The three bullets that slammed into her son yanked Smith into a unwelcome group. She joined the ranks of the family members of the 119 people killed in Chattanooga during the last five years.

Her pain, echoed 118 times.

There’s the 3-year-old girl who was raped, then beaten to death.

The 19-year-old new mother gunned down in the street.

The 66-year-old stabbed to death inside his apartment.

Tatiana Emerson, 3. Jasmine Akins, 19. Robert Rutledge, 66.

The toll that homicide takes on a city is hard to measure. There’s the immediate searing loss of death, the choked sobs of a grandmother and the wails of disbelief as a friend collapses just outside the yellow police tape.

But then there’s the dull, constant emotional pain that never really disappears. The economic loss of the victim’s potential life and earning power. There’s the tension and fear at high schools when a student is killed. The cost of the counseling, of the police investigation, of the trial and incarceration of a suspect.

On average, each murder costs society $17 million, according to a study published in the The Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology in 2010. The researchers looked at 654 murder cases and quantified the costs of the victim’s death, the court system, lost productivity and the public’s willingness to pay for crime prevention programs to stop murder.

By that count, Chattanooga will spend more than $408 million on just 2015’s homicides. For all 119 homicides since 2011, the cost is higher than $2 billion.

"It takes a toll on lives," said Verna Wyatt, whose sister-in-law was raped and murdered in Nashville in 1991, prompting her to serve as executive director for nonprofit Tennessee Voices for Victims.

"When you drop that pebble in, there is that immediate impact, but then it affects so many people," she said. "Family, friends, acquaintances, teachers, students — it just cascades on down."

****

Vanessa Buckner drove from Chattanooga to Nashville on Tuesday to sit in a parole hearing for the man she believes killed her son, 20-year-old Quincy Bell.

Police think he’s the killer, too: Marcus Boston was arrested three months after Bell was shot while driving on Wilcox Boulevard on Sept. 22, 2012. But when a witness failed to show at a hearing in 2013, the charges were dismissed for lack of evidence.

Boston was jailed on unrelated drug charges. So Buckner goes to his parole hearings to make sure he stays behind bars. And every Sept. 22, she visits her son’s grave, stops by the gas station where he died. She still orders a cake for his birthday every year. She cares for two of his children regularly while their mothers are at work.

"Nothing has changed," she said. "People say it gets better as time goes on. But it hasn’t for me. I still cry every day. I didn’t know a person could cry for three years."

Bell is Chattanooga’s typical homicide victim: black, male, in his 20s. A Times Free Press analysis of the 119 people killed in Chattanooga between 2011 and 2015 showed that, in cases where race could be determined, 80 percent of the people killed were black.

Eighty-two percent were male. And the majority — 65 percent — were black males.

Plotted on a map, the homicides are clearly clustered in Chattanooga’s poorer neighborhoods, often in or around the city’s public housing complexes. In the two ZIP codes with the most homicides, 66 percent and 38 percent of the populations live below the poverty level, according to U.S. census data.

The school zones for The Howard School and Brainerd High School include 87 of the city’s 119 murders. Both schools have the lowest graduation rates and lowest ACT scores of all traditional public schools in Chattanooga.

Dr. Elenora Woods, president of the local NAACP, sees statistics like that as proof that homicide is driven by underlying problems — poverty and lack of opportunity.

"People are going to fight and steal and kill to live," she said. "No matter what country you are in, if there is only one glass of water and everybody is thirsty, the person who gets the water is the one who gets to it first — or kills someone to get there. And we're seeing that."

About 40 percent of the city’s homicides involved a victim or suspect in a gang, according to police records. But perhaps the most ubiquitous factor among Chattanooga’s homicides is some involvement with illegal drugs, said Sgt. Bill Phillips, who now heads the department’s homicide cold-case unit.

It could be a home is targeted for a robbery because the suspect knows narcotics are sold from the house. It could be a drug deal gone wrong. Or it could just be that people are high and something happens that wouldn’t have normally, he said.

Newspapers have no problem describing the victims of homicides being black, so why refrain from discussing the race of the suspects?

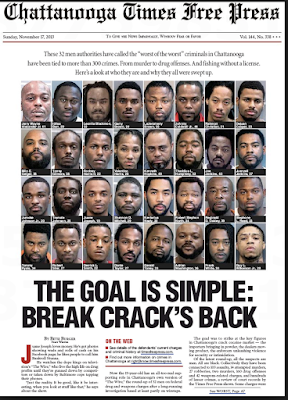

Oh … that’s because the newspaper got in trouble for posting pictures of the "worst of the worst" criminals. Hint: they were all black. [A look at the 32 suspects authorities called 'worst of the worst' criminals in Chattanooga, Chattanooga Times Free Press, November 17, 2013]

Again: when can we stop pretending black people in America are our greatest untapped asset and realize they represent our greatest (and most obvious) liability?

This is a content archive of VDARE.com, which Letitia James forced off of the Internet using lawfare.