By Steve Sailer

07/25/2022

Earlier: James Patterson: Not All White Authors …

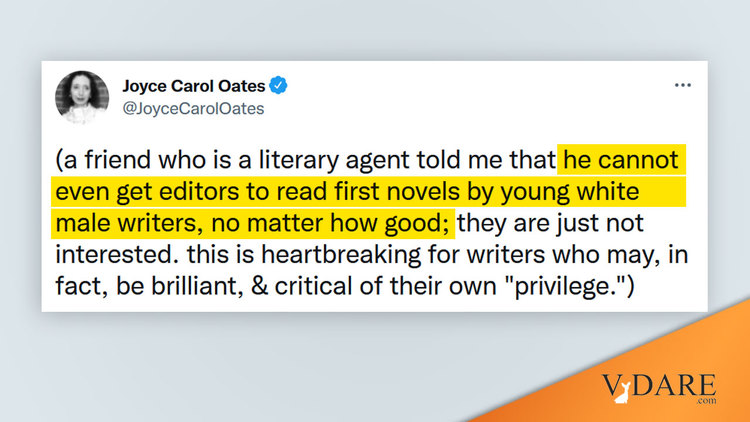

Veteran literary novelist Joyce Carol Oates remarks on the bias against young white male authors in today’s publishing industry. She immediately gets ratioed by hundreds of angry replies telling her that young white men are not discriminated against but ought to be:

Others have noticed the same trend. From The Guardian (with a London rather than New York set of examples, but I doubt the pattern is much different on this side of the Atlantic):

How women conquered the world of fiction

by Johanna Thomas-Corr

@JohannaTC

Sun 16 May 2021In March, Vintage, one of the UK’s largest literary fiction divisions, announced the five debut novelists it would be championing this year: Megan Nolan, Pip Williams, Ailsa McFarlane, Jo Hamya and Vera Kurian.

All five of them are women. But you could be forgiven for not noticing it, so commonplace are female-dominated lists in 2021. Over the past 12 months, almost all of the buzz in fiction has been around young women: Patricia Lockwood, Yaa Gyasi, Raven Leilani, Avni Doshi, Lauren Oyler. . … The energy, as anyone in the publishing world will tell you, is with women.

So is the media coverage. Over the past five years, the Observer’s annual debut novelist feature has showcased 44 writers, 33 of whom were female. You will find similar ratios on prize shortlists. Men were missing among the recent names of nominees for the Costa first novel award. Here, too, the shortlisted authors over the past five years have been 75% female. This year’s Rathbones prize featured only one man on a shortlist of eight. The Dylan Thomas prize shortlist found room for one man (as well as a non-binary author), and so too did the Author’s Club best first novel award, which prompted the chair of judges, Lucy Popescu, to remark: “It’s lovely to see women dominating the shortlist.”

Judges take pride in being biased.

But not everyone in publishing sees it in such benign terms. “Why is that ‘lovely to see’?” a male publisher emailed me shortly after the list was announced. “Can you imagine the opposite, a shortlist of five men and one woman, about which the chair says, ‘It’s lovely to see men dominating the shortlist’?”

A generation ago the shortlists were dominated by men: the “big beasts” of the 80s and 90s. Martin Amis, Julian Barnes, Ian McEwan, William Boyd, Kazuo Ishiguro et al in the UK and Philip Roth, John Updike and Saul Bellow in the US. The writers we considered our leading novelists were men. This has changed, and while it is almost universally accepted with publishing that the current era of female dominance is positive — not to mention overdue and necessary, considering the previous 6,000 or so years of male cultural hegemony — there are, increasingly, dissenting voices among publishers, agents and writers. They feel that men — and especially young men — are being shut out of an industry that is blind to its own prejudices.

That male publisher is at pains to point out that, yes, “the exciting writing is coming from women right now” and that he himself publishes more women. But this is “because there aren’t that many men around. Men aren’t coming through.”

Many women may instinctively take a dim view of men saying they need better representation. There were similar worries voiced when girls started to do better in their GCSEs than boys; there are whenever women are able to compete on equal terms to men. And certainly, when you raise this issue with anyone in publishing, you tend to receive an eye-roll — perhaps followed by a “Hang on! Wasn’t last year’s Booker prize-winner a man?” Those who don’t believe there is a problem will pounce on Douglas Stuart, author of Shuggie Bain, as evidence of male supremacy. But they will often struggle to name younger men making their way on to awards lists or bestseller charts. There’s Max Porter… Sam Byers… a handful of Americans such as Ben Lerner and Brandon Taylor. Yet few of these men are household names and none has anything like the cultural buzz of a Sally Rooney.

Why is this? That same male publisher points to the Vintage promotion in particular, noting that almost all the editors in that division are female. (Of 19 editors commissioning fiction at Vintage, only four are men.) And this isn’t just one team in one company, he argues — it’s a gender balance replicated across the industry. (A diversity survey, released in February by the UK Publishers Association, had 64% of the publishing workforce as female with women making up 78% of editorial, 83% of marketing and 92% of publicity.)

“Whenever I send out a novel to editors, the list [of names] is nearly all female,” a male agent says. Like the publisher — who fears being seen as “some kind of men’s rights activist” — he will only speak on condition of anonymity. The subject is such a hornet’s nest that almost every man in the books industry who I approached refused to speak on the record for fear of the backlash.

“I’ve grumbled about it for years whenever I’m at a publishing dinner party. I get roundly told to shut up,” the agent says. But it’s not the gender make-up that bothers him, he insists, it’s the prevailing groupthink — the lack of interest in male novelists and the widespread idea that the male voice is problematic.

“I was having a meeting the other day with yet another 28-year-old woman,” he continues. “I always ask editors, ‘What are you looking for’, and she happened to say, ‘What I really want is a generational family drama’. I said, ‘Oh, like The Corrections by Jonathan Franzen?’ and honestly, you would think I’d said Mein Kampf. She said, ‘No! Nothing like that!’. And I thought, ‘But that’s literally what you’ve described!’”

Hannah Westland, publisher of the literary imprint Serpent’s Tail, says she’s not always confident that there’s a market for fiction written by young men. “If a really good novel by a male writer lands on my desk, I do genuinely say to myself, this will be more difficult to publish.” She believes that the “paths to success” are narrower because there are fewer prizes open to men, fewer magazines that will cover male authors, and fewer media figures willing to champion them — in the way that, for example, Dolly Alderton and Pandora Sykes have championed female authors on their podcasts.

According to figures obtained from the Bookseller, 629 of the 1,000 bestselling fiction titles from 2020 were written by women (27 were co-authored by men and women and three were by non-binary writers, leaving 341 by men). Within the “general and literary fiction” category, 75% were by female authors — 75% female-25% male appearing to be something of a golden ratio in contemporary publishing.

The general consensus is that young male writers have given up on literary fiction. They see more possibilities in narrative nonfiction (particularly travelogues and nature writing in the vein of Robert Macfarlane) or genre fiction (especially crime and sci-fi), which is less mediated by the culture and the conversations on Twitter.

… “What’s really interesting is that if I’m publishing a black, gay man, I’m more likely to gain traction with their story because it’s considered original and it fits the #diversevoices box,” she says. “Whereas if it’s a white, working-class man, it seems to be much harder to break through.”

… But regardless of class, do men, or at least male readers, actually want a look-in? Whenever I speak to men in their 20s, 30s and 40s, most tell me they couldn’t give a toss about fiction, especially literary fiction. They have video games, YouTube, nonfiction, podcasts, magazines, Netflix. Megan Nolan, whose debut novel, Acts of Desperation, is one of this year’s biggest literary hits, says: “The only men I know who actively seek out and read fiction work in that field. I don’t think many men I know would read more than one novel every two years.”

… Male writers definitely seem to be feeling more reticent about sex. Choire Sicha argued more than a decade ago in the New York Observer that his generation of male novelists (Jonathan Safran Foer, Joshua Ferris, Dave Eggers) had become emasculated. They were “malformed, self-centered boy-writers” — anti-Mailers who shied away from sex and controversy. …

“They think that to be allowed a place at the table, they need to have the right views and be these nice guys. They’re in danger of rendering themselves even less worth reading than they are already.”

… Karolina Sutton, an agent at Curtis Brown, is surprised that men are feeling excluded from fiction. She stresses that it has taken women centuries to find their voice and be confident within publishing: “Why wasn’t there uproar in the media when women were excluded?” she asks.

Women weren’t excluded from publishing novels. Of the top 10 bestselling novels of the year in the U.S., women wrote between 31% and 41% in the first four decades, before dropping with coming of WWII (which I’m guessing provided men with lots of great material).

She insists that there are plenty of successful young male writers, it’s just most of them aren’t writing from the dominant point of view or with the self-assurance that Roth and Amis had in the 80s or 90s. Still, she concedes that the expectations of male debut novelists are greater than they used to be: “For a young man to get a quarter of a million pound advance, the bar is really high. They have to deliver something really spectacular. It’s easier for women to get higher advances.”

You would have to go back 12 years, to debuts by Ross Raisin and Joe Dunthorne, to see big money spent on new male voices. Although Caleb Azumah Nelson’s Open Water, published in February, is said to have received a “significant” advance after a nine-way bidding war, many agents and editors have told me how rare that is. Sutton believes this is because “the cultural moment belongs to women”, whose stories “seem to feel more fresh”.

Are women’s stories really more fresh? My impression is that Jane Austen is by far the biggest selling 19th century novelist of the 21st century (unless there’s some 19th century book that’s always assigned in school the way The Great Gatsby is). The reason Austen speaks so well to women two hundred years later is because their interests don’t really change that much.

But the anonymous male publisher I spoke to feels we should be wary of the argument that men aren’t currently producing “fresh” fiction. “There’s a flip side to that. Are we really going to say that 15 years ago, black women weren’t writing good books?”

Any feminist is likely to feel conflicted about all this. There is clearly a hegemony emerging in the publishing world, one that Lovegrove refers to as “white feminism”, which threatens to make fiction stale and predictable, as well as alienating potential young male readers. It’s both amusing and dismaying that the publishing insiders I speak to all seem to identify their archetypal reader as a 28-year-old white woman who grew up in Buckinghamshire or Oxfordshire.

But I think we should be wary of shaming the women whose enthusiasm, passion and investment keeps the whole industry afloat. And there is also the question of whether for all their visibility, women are yet afforded the same cultural respect as the male novelist. There’s a danger that the novel gets dismissed as a feminised form, especially since the history of the novel, from its 18th-century origins, was rooted in the idea of it as frivolous literature for leisured women who didn’t receive a formal education in science or politics. It was male writers such as Samuel Richardson, as well as a generation of male critics, who were seen to professionalise fiction writing.

The male mind is vastly more obsessed with discerning hierarchies of greatness in the past. The female mind is much more interested in what’s new and in fashion. (Which is one reason why Jane Austen’s hegemony over chick lit is so extraordinary.)

A few thoughts judging from the replies to Joyce Carol Oates:

White women appear to be counted as (dis)honorary white men for the purposes of calculating how white male dominated the publishing industry is. As I pointed out recently during the similar James Patterson brouhaha (and what do Joyce Carol Oates and James Patterson know about the book business?), the great majority of employees of publishing houses are not white men but white women. But the concept that whites white men seems hard for many people with literary turns of mind to grasp these days.

The Woke don’t seem all that aware of how sexual reproduction works. For example, I get the impression that they think young white male authors deserve to pay because they are descended from men, while women authors are only descended from women, not from icky men.

Of course, we are all really descended from women and men. (Duh.) In contrast, my impression is that high achieving women are more likely to be products of The Patriarchy than are high achieving men. Women who achieve at a high level in a typically male dominated field tend to have strong fathers in their lives, I suspect. Can anybody think of a database for testing this?