By Steve Sailer

10/13/2022

Law professor Mary Ellen Turpel-Lafond is a well-known member of Canada’s Great and the Good.

She’s received eleven honorary degrees from law schools for being the first Canadian Amerindian this and that, despite being extremely white-looking.

She’s received eleven honorary degrees from law schools for being the first Canadian Amerindian this and that, despite being extremely white-looking.

Not surprisingly, a long investigative report by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation can’t find any evidence of her actually being an Indian.

Prominent scholar and former judge Mary Ellen Turpel-Lafond says she is a treaty Indian of Cree ancestry — but her claims don’t appear to match the historical record. Her story illuminates a complex and growing discussion about Indigenous identity that’s playing out across the country.

By Geoff Leo

Senior Investigative Reporter

Oct. 12, 2022… A 2021 recipient of the Order of Canada, Turpel-Lafond is considered to be one of the most accomplished and decorated Indigenous scholars in Canadian history.

She rose to national prominence during the Charlottetown Accord debates in the 1990s as a constitutional adviser to Ovide Mercredi, the national chief of the Assembly of First Nations. …

The 59-year-old Harvard- and Cambridge-educated lawyer and professor says she’s biologically Cree through her father, who grew up on the Norway House Cree Nation in Manitoba. She has also said she’s a treaty Indian who was originally connected to Norway House. Later in life, she transferred to her husband’s community: the Muskeg Lake Cree Nation in Saskatchewan.

A 1989 academic article she wrote about Indigenous people and the Canadian Constitution included a biography that referenced her First Nations name: “Mary Ellen Turpel is Aki-Kwe. Born of a Cree father and an Anglo-Canadian mother.”

In 1998, she was appointed as a provincial court judge in Saskatchewan, which she has said made her “the first treaty Indian to be appointed to the court“ in the province’s history. She has said her “First Nations background and Cree background” brought “extra value to my understanding of what I see in the courtroom.”

A 2017 Globe and Mail story said that amid growing pressure to put an Indigenous jurist on the Supreme Court, Turpel-Lafond’s name was one of two most commonly mentioned.

… Turpel-Lafond’s accomplishments have earned her international attention. In 1994, Time magazine named her one of “The Global 100” leaders of the new millennium, alongside the likes of Bill Gates and former U.S. secretary of state Condoleezza Rice, for her role in Canada’s constitutional debates. In 1999, the magazine selected her one of the top Canadian “leaders for the 21st century,” recognized for her work building a “more inclusive legal system” and championing “restorative justice.”

It all seems even more astounding when set against her personal history.

“Mary Ellen Turpel-Lafond grew up in poverty in Norway House, Manitoba,” Jutras told the crowd at the McGill ceremony in 2014. The Norway House is an isolated northern community consisting of the Norway House Cree Nation and a small municipality.

“As a child, she was surrounded by domestic violence. But she has lived her own life at a furious pace, urging other marginalized women to become the masters of their own destiny,” Jutras said. …

CBC located more than a dozen news stories written over the past 30 years that addressed Turpel-Lafond’s early years. Virtually all indicate she was born and/or raised in Norway House or on a Manitoba reserve. …

The Saturday Night magazine article described the home life she and her three older sisters experienced as children in Norway House. “Like so many Native homes, hers was rife with alcoholism, poverty and violence. She regularly witnessed her father striking her mother and suffered abuse herself.”

But, nah, she was born and grew up in Niagara Falls.

But, nah, she was born and grew up in Niagara Falls.

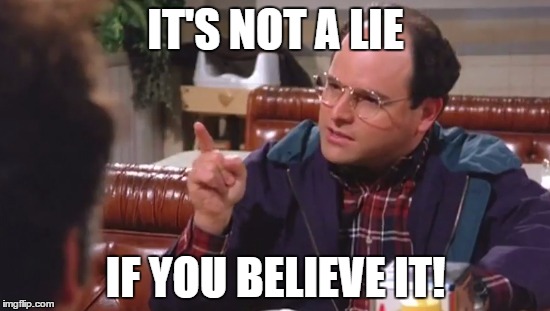

It strikes me that she probably sort of believes her claims that her late father Bill Turpel was of partial Indian descent. Maybe she heard them from her father.

Her father spent some years as a child living at Norway House on an Indian reservation. But he wasn’t an Indian himself. His father was the white doctor sent by the government to care for the Indians and his mother was an English immigrant.

Within the family, there are differing opinions on the late Bill. One cousin thinks his Uncle Bill was part Indian:

Jim said he continues to believe his uncle was Indigenous. He said as an adult, his Uncle Bill looked very different from the rest of the family — shorter and stockier, with darker skin. …

He said Uncle Bill was a “wild” character with a “serious drinking problem”…

Of course, there have been white Canadians with serious drinking problems too. Perhaps it seems more tragically romantic if your alcoholic wife-beater dad is an Indian alcoholic wife-beater?

Jim said his grandfather, Dr. Turpel, also took note of Uncle Bill’s eccentricities.

“I recall my grandfather frequently saying ‘that’s the Native in him’ when he would do something that no one seemed to understand, which was really frequent,” Jim said. He said he tried talking to his dad about Uncle Bill’s biological descent, but his father declined — a fact Jim found to be out of character for his father.

Jim’s mother, Barbara, told CBC she has her doubts that William was Indigenous, believing instead that he was the child of Dr. and Mrs. Turpel.

She said he and her husband “looked like brothers, although [William] was smaller.”

The CBC article goes to some lengths to rule out possibilities of Bill being part Indian, such as that Bill was the son of the doctor and a reservation woman: they tracked down a birth announcement in Victoria.

But I wouldn’t at all be surprised if Turpel-Lafond decided as a child that her father was Indian and that she constructed her identity around that, and then didn’t look for disconfirmatory evidence. That wouldn’t be the worst thing ever.

But the CBC assembles a lot of evidence that Turpel-Lafond shades the truth to aid her ambitiousness. Here’s an interesting section. One of the only times I’ve seen the mainstream media present evidence that somebody benefitted from affirmative action:

Turpel-Lafond told CBC her career success is not related to her claim to Indigenous ancestry.

“I have competed for every job alongside all other candidates,” she wrote. “Although I have often worked in the fields of Indigenous justice and child welfare, I have never been awarded a position on an affirmative-action basis.” Affirmative action is the practice of prioritizing the hiring of a specific demographic group that has historically faced discrimination.

This is a point that Turpel-Lafond has been making for years. A 1995 profile of her career in the Ottawa Citizen said she “is proud that she did not get ahead through affirmative-action programs for Natives.”

However, CBC has found documentation that appears to show that early in her career, Turpel-Lafond was targeted for hire at Dalhousie University in part because of her Indigenous ancestry.

In a 1990 interview published in the book Dalhousie Law School — An Oral History, then-professor Faye Woodman noted that in the 1980s, the law school began an aggressive and successful affirmative-action campaign to hire female professors. That success prompted Woodman to exclaim “the thing that impresses me most about the law school is the program of affirmative action.”

However, she noted, “for Aboriginal people and Black people, it is a dismal situation, right across Canada.” Woodman said this prompted the university to target “two Aboriginal women” for hire: Patricia Monture and Mary Ellen Turpel.

“We worked very hard as an appointments committee to encourage them to come,” Woodman recalled. “We coaxed them and tried to persuade them in every way that we could think.”

Turpel-Lafond started work as a law professor at Dalhousie on July 1, 1989.

Of course, if she weren’t white, they’d never mention it.