08/11/2018

It’s interesting to see The New York Times sympathetic approach to Lebanese citizens who feel overwhelmed by the million-plus horde of Syrian refugees who have flooded their nation. The Lebanese are angry about downward pressure on wages, worsened crime, stressed infrastructure, and other problems caused by the foreigner invasion.

In comparison, the Times’ attitude toward Americans has been less generous to say the least, and the paper prefers the California acquiescence as the ideal social model rather than an insistence on assimilation.

But diversity’s difficulties look a little different from a great distance, as the Times story does observe the normal stresses and reactions that happen when a nation is burdened with an enormous influx of needy foreigners.

The story got a front-page placement in Thursday’s paper.

The story was reprinted in an obscure website:

In Lebanon Town, Refugees and Locals Agree on 1 Thing: Time for Syrians to Go, UpdateNews.news, August 9, 2018

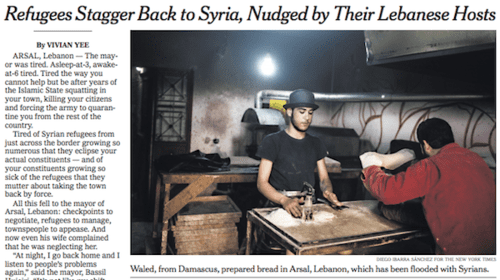

ARSAL, Lebanon — The mayor was tired. Asleep-at-3, awake-at-6 tired. Tired the way you cannot help but be after years of the Islamic State squatting in your town, killing your citizens and forcing the army to quarantine you from the rest of the country.

Tired of Syrian refugees from just across the border growing so numerous that they eclipse your actual constituents — and of your constituents growing so sick of the refugees that they mutter about taking the town back by force.

All this fell to the mayor of Arsal, Lebanon: checkpoints to negotiate, refugees to manage, townspeople to appease. And now even his wife complained that he was neglecting her.

“At night, I go back home and I listen to people’s problems again,” said the mayor, Bassil Hujeiri. “It’s not like my shift ends and I get to close the door.” [ … ]

Lebanon has taken in so many Syrians — more than a million — that they now make up a quarter of the country’s population. But the welcome has not always been gracious.

Lebanese authorities never gave full rights to the hundreds of thousands of Palestinian refugees who have lived in Lebanon since the 1940s and ’60s, even as the refugee camps have become permanent cities. Apparently learning from that experience, the government has prohibited the establishment of refugee camps and made the Syrians’ lives difficult, in ways large and small, in the hope that they would return as soon as possible.

Most Syrians in Lebanon cannot move freely around the country. They are banned from some public parks and certain jobs. The small minority of Syrian children who attend school are largely separated from Lebanese children.

Town cemeteries often refuse to bury Syrian bodies. Many landlords reject Syrian tenants. History — Syrian troops occupied Lebanon from 1976 to 2005 — is not improving guest-host relations. Nor are Lebanese sensitivities about the country’s fragile sectarian balance, which Lebanese leaders fear would be upended by the settlement of the mainly Sunni refugees.

“We don’t have any safety guarantees from Assad, but it’s better there than here,” said Mohamed Abdul Aziz, a father of six from the same village as Mr. Ishac. “We have a choice between the bad and the worst.”

Much like populists across Europe and the United States fulminating against immigrants, Lebanese politicians blame Syrians for dragging down wages, dialing up crime and overtaxing infrastructure. Across the country, Syrian refugees have been evicted, deported, beaten and even killed by Lebanese.

Unsurprising, then, to hear Lebanese leaders pressing for their return. (Continues)