02/10/2020

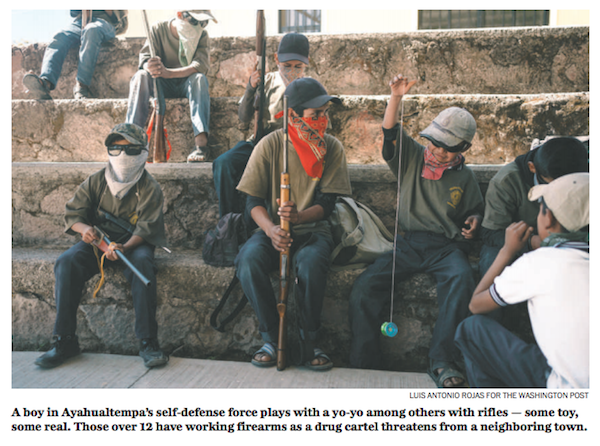

Sunday’s Washington Post had a front-page article reminding us of what a barbaric country lies to our south. The accompanying photo shows young boys holding rifles with the headline, “Amid gang peril, a Mexican village arms its children.”

What could possibly go wrong? Even proponents of armed self-defense (like me) see serious dangers with kids’ immature brains that cannot always judge what’s real and who exactly might be a real enemy.

Apart from the kiddie angle, we can see how completely Mexico is owned by criminal cartels.

As the article mentions, Mexico had a record 35,588 homicides in 2019, showing the nation next door is one of the more violent on earth.

President Trump should finish building the wall yesterday and reinforce it with armed troops. It’s crazy to have an insecure border with such a savage nation.

Amid gang peril, a Mexican village arms its children, by Kevin Sieff, Washington Post, February 8, 2020

AYAHUALTEMPA, Mexico — Before he picked up a rifle and joined a squad of armed children, Alex wanted to become a schoolteacher. He’d teach anything — “whatever the principal asks” — because spending his days in a classroom sounded pretty good.

He was 13, a B student with a Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles bicycle who got nervous around the girls in his middle school.

Then, in November, as violence surged in the mountains of Guerrero state, the men of Ayahualtempa decided it was time for their sons to take up arms.

Alex was handed a hunting rifle and told to show up for daily training on the village basketball court. He and his young comrades, some as young as 6, marched and crawled with loaded guns almost as tall as they were. Their uniforms said “Community Police” in yellow letters.

When the photographers started coming, the boys were told to cover their faces with handkerchiefs. Arming children to defend the town against a violent gang wasn’t a media stunt, Alex’s commanders insisted. Yet if the images drew the government’s attention to a place Mexico’s security forces had forgotten, it would be a triumph of its own.

But were the boys training to defend their village, or were they being paraded in front of visiting photographers to send a message to the government, a plea for more resources? Sometimes even Alex wasn’t sure. What he knew was that the gun was heavy and loaded, and the training felt real enough to him.

Alex’s father, Santos Martínez, looked at his son’s face, trying to gauge whether Alex was mature enough to join the force.

“There was no fear in his eyes,” Martínez said. “That’s how I knew he was ready.”

Alex repeated the words of his commander: “I’m preparing to defend my village.”

Mexico suffered 35,588 homicides in 2019, a record. It was another data point in a trend borne out across Ayahualtempa and thousands of towns like it: Every year, no matter who is in power, this country becomes more violent.

But violence takes dramatically different forms across Mexico, a nation splintered by turf wars. In the northwestern capital of Culiacán, the Sinaloa cartel battles the country’s security forces with military-grade weapons. In Ayahualtempa, a village of 600 indigenous people, the community police carry aging hunting rifles in their own war against a powerful drug cartel called Los Ardillos, which controls the neighboring town.

For years, Ayahualtempa had maintained its own defense force, dozens of armed men who patrolled the village and manned checkpoints and held overwatch positions on the roofs of unfinished homes. Autodefensas, or self-defense forces, are legal in Guerrero state and recognized by the federal government.

But over the past year, the local autodefensa, known as the CRAC-PF, has been overwhelmed. Twenty-six people have been killed since the start of 2019 in the force’s territory, which includes Ayahualtempa and 15 other towns. Last month, 10 musicians from those towns traveling to a concert were shot and burned beyond recognition. One of them was 15 years old.

Alex’s middle school was in what was considered to be enemy territory. He stopped attending. (Continues)