NEW YORK MAGAZINE On Baltimore Killings: "Baltimore, the Laboratory City"

By Steve Sailer

12/01/2015

Excerpts from a long article in New York about the high homicide rate in Baltimore after the riots.

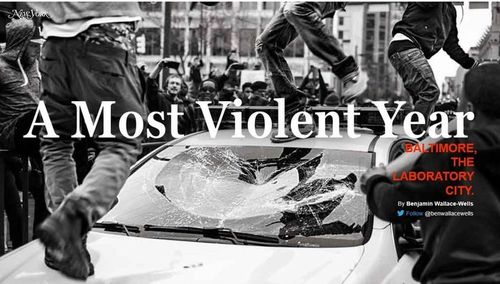

A Most Violent YearBALTIMORE, THE LABORATORY CITY

by Benjamin Wallace-Wells

… Each of the American cities where high-profile police killings have inspired demonstrations these past three years has had a different experience of violence, of political protest, of social change — each is part of a composite. Baltimore’s has been the most prolonged: After Gray’s killing, and then after the protests, there was a third phase, more devastating than anywhere else, in which the police seemed to retreat and then the largest wave of homicides in a quarter-century overwhelmed the city. That wave has still not fully subsided; the disturbance that became visible with Gray’s death continues.

I’m not a big opponent of the passive voice in writing, but the tendency of journalists to lapse into the passive voice when describing black violence is not a coincidence.

… There was something else unique to Baltimore’s experience that deepened its tragedy and mystery. Baltimore’s political leadership is composed almost entirely of progressive African-Americans, many of whom had marched in Black Lives Matter protests.

Is it really that mysterious or unique?

So why has the homicide rate been so high ever since the riots?

… In the first four months of the year, Baltimore’s police had arrested a monthly average of 2,630 people. In May, that number dropped almost in half, to 1,557. The uniformed police, Commissioner Batts would later say, had “taken a knee.”The shape of public order changed. Russell met a man who ran a West Baltimore halfway house for recovering addicts, most of them heroin abusers, and the counselor called him one day with a comically outsize problem. Streetside dealing had so flourished, the man said, that his residents had to walk past 17 separate locations where dealers were actively selling heroin just to get to the methadone clinic.

Eventually, the cops got back to work, but the killings went on.

… Baltimore, in its poverty and violence, is a laboratory city, its poorest neighborhoods subject to constant social-science observation and experiment; there are data sets reaching back years that detail the number of chicken bones left discarded on select city blocks (as a measure of social disorder) and the number of men clustering outside liquor stores on weekend nights.

The South Side of Chicago is another closely studied city, with the U. of Chicago sociology department having been a world leader since the 1920s or so. I don’t see much correlation between intensive social science attention, such as in Baltimore and Chicago, and good outcomes such as a low homicide rate. It would make an interesting social science study to correlate the depth of social science research in a city and the murder rate. My vague impression is that homicide rates tend to be lower in lower brow cities like San Antonio than in cities with elite research universities like U of C and Johns Hopkins.

Many of these records are maintained by a professor at Johns Hopkins named Debra Furr-Holden, and she could see the data change almost immediately. With so many stores burned or closed, simply conducting your daily business — commuting, shopping — meant you had to travel farther, often outside your neighborhood, sometimes into places you would not have considered safe. The people who had come out of their houses during the protests did not go back inside; for the first part of the summer, something like double the ordinary number of people were outside in the evenings.

Maybe the government should distribute free video games to get people back on their couches? Playing Grand Theft Auto is better than committing Grand Theft Auto.

More headscratching:

All of the public talk in the city was about unity. The pleas to end the violence were by that point ubiquitous. But just as all of Baltimore pondered the mystery of how a progressive city could produce such a despotic police force, a second mystery had presented itself: If everyone was organized to prevent violence, why did it continue to happen? The cops were back at their posts. The whole city had been politicized. The poorest streets were filled with activist group meetings and sermons. The gangs were professing nonviolence. Still, the murders continued.

This sounds very much like Tom Wolfe’s Mau-Mauing the Flak Catchers from 1970 about the San Francisco ghetto:

Whites were still in the dark about the ghettos. They had been studying the “urban Negro” in every way they could think of for fifteen years, but they found out they didn’t know any more about the ghettos than when they started. Every time there was a riot, whites would call on “Negro leaders” to try to cool it, only to find out that the Negro leaders didn’t have any followers. They sent Martin Luther King into Chicago and the people ignored him. They sent Dick Gregory into Watts and the people hooted at him and threw beer cans. During the riot in Hunters Point, the mayor of San Francsco, John Shelley, went into Hunters Point with the only black member of the Board of Supervisors, and the brothers threw rocks at both of them. They sent in the middle-class black members of the Human Rights Commission, and the brothers laughed at them and called them Toms. Then they figured the leadership of the riot was “the gangs,” so they went in the “ex-gang leaders” from groups like Youth for Service to make a “liaison with the key gang leaders.” What they didn’t know was that Hunters Point and a lot of ghettos were so disorganized, there weren’t even any “key gangs,” much less “key gang leaders,” in there. That riot finally just burnt itself out after five days, that was all.

Here’s one interesting point from Wallace-Wells’ article about an occasional effect of Ending the Era of Mass Incarceration. All respectable opinion is agreed that we must let older cons out of prison. Except, sometimes when they hit the streets, that just sets off new rounds of vengeance violence:

Barksdale mentioned one source of tension the interrupters were working to defuse. A man had just been released from prison, where he had served more than a decade for murder, and had returned to his old neighborhood. The victim’s son, now in his early teens, had become aware that his father’s murderer was in the neighborhood and had mentioned the fact to some friends of his. One of the friends had a family connection to the paroled murderer, and so the murderer knew that the son knew that he was around.The interrupters had met both the man and the boy. Barksdale believed that the man wanted to go straight, and the boy was a good kid, by nature given to following rules and heeding advice. Nevertheless, it had become a situation. The expectation that the boy might try to avenge his father’s death meant that both the man and the boy had reason to believe the other might try to kill him.