By Allan Wall

04/27/2021

Demographics is Destiny. But demographic trends don’t always stay the same, and they aren’t set in stone.

The New York Times reports new data from the Census Bureau that shows slow population growth in the past decade:

Over the past decade, the United States population grew at the second slowest rate since the government started counting in 1790, the Census Bureau reported on Monday [April 26], a remarkable slackening that was driven by a slowdown in immigration and a declining birthrate.

[U.S. Population Over Last Decade Grew at Slowest Rate Since 1930s, by Sabrina Tavernise and Robert Gebeloff, New York Times, April 26, 2021]

Note that it attributes the slow growth rate to two factors: 1) immigration slowdown and 2) declining birthrate.

There are political ramifications:

The bureau also reported changes to the nation’s political map: The long-running trend of the South and the West gaining population — and the congressional representation that comes with it — at the expense of the Northeast and the Midwest continued, with Texas gaining two seats and Florida one, and New York and Ohio each losing one. California, long a leader in population growth, lost a seat for the first time in history.

The data will be used to reapportion seats in Congress and, in turn, the Electoral College, based on new state population counts. The count is critical for billions of dollars in federal funding as well as state and local planning around everything from schools to housing to hospitals.

In Congress, some states are losing seats, others are winning seats.

In all, six states gained congressional seats: Colorado, Florida, Montana, North Carolina, Oregon and Texas, which gained two. Seven lost a seat: California, Illinois, Michigan, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania and West Virginia.

Some states were incredibly close: New York was just 89 people short of keeping its seat, an expert at the Census Bureau said.

You'd think they could have scrounged up 89 more people somewhere in New York. Oh well …

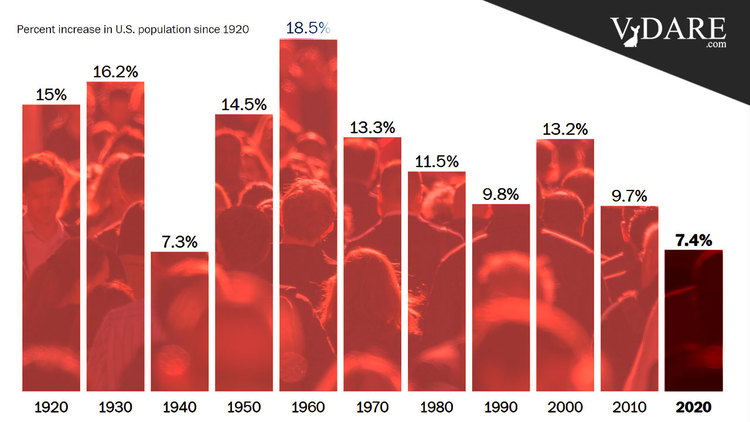

The new decennial census counted 331,449,281 Americans as of April 1, 2020, said Dr. Ron Jarmin, the acting director of the Census Bureau. The total was up by 7.4 percent over the previous decade, slightly more than in the 1930s, when the population grew by just 7.3 percent. In that period, the birthrate rose once the economy started to climb out of the Great Depression. But this time it has continued to decline, after dropping in the wake of the Great Recession in 2008.

The lower birthrate, combined with the decline in inflows of immigrants and shifting age demographics — there are now more Americans 80 and older than 2 or younger — means the United States may be entering an era of substantially lower population growth, demographers said. This would put the United States in line with the countries of Europe and East Asia that face serious long-term challenges with rapidly aging populations.

“This is a big deal,” said Ronald Lee, a demographer who founded the Center on the Economics and Demography of Aging at the University of California, Berkeley, noting that the United States had long outpaced other developed countries in population. “If it stays lower like this, it means the end of American exceptionalism in this regard.”

The once-in-a-decade process of counting all Americans redistributes political power based on where in the country people have moved. States that lose seats are not necessarily losing population, but are growing more slowly than the nation as a whole.

The article discusses immigration.

Another defining feature of the decade was the fall in immigration. The rates of new immigrants had been rising for years, since a modern low in the 1970s. But they mostly leveled off after the Great Recession in 2008, and went into decline during the coronavirus pandemic, said Jeffrey Passel, senior demographer at the Pew Research Center.

However, we haven’t had a good governmental estimate of the amount of illegal aliens in the country for years.

Plus, we now have the Biden Rush on the border and other possible changes afoot.

Mr. Passel said the drivers were a worsening economy in the United States and tougher enforcement on the border with Mexico, especially after 2010. Also important, he said, were Mexico’s improving economy and its own lower birthrate.

That’s true about the Mexican birthrate.

“The change in the Mexican flows is really what caused immigration to level off,” Mr. Passel said, noting that Mexico had been the biggest source of immigration to the United States for years. He has calculated that, throughout the decade, there were more unauthorized Mexican immigrants leaving the United States than arriving.

Then again, Mexican emigration to the U.S. may be increasing again. Trends change.

The tapering of immigration over all has added to population woes in some states. Over the last decade, three had outright population declines: West Virginia, Mississippi and Illinois.

The fact that the population has gone down in those states should not be used as an excuse for more mass immigration.

Also, birthrates change.

The final driver of the country’s extraordinarily sluggish growth over the past decade is a stubbornly persistent decline in the birthrate that has surprised demographers and prompted a debate over whether the delay in childbearing is a permanent new fixture in the lives of American women.

Aging populations can mean higher burdens for elder care, and slower labor force growth, with broad implications for the economy and the social safety net. But population slowdowns can also mean an improved outlook for the climate, said Professor Lee, who is also an economist. And fertility declines also reflect women’s rising roles as professionals and labor force participants.

It is far from clear, Professor Lee said, where the birthrate decline that has taken hold in many rich countries is leading.

“It’s uncharted waters,” he said. “The consequences of low fertility are still unfolding.”

Bottom line: Demographic trends change.