NEW YORK TIMES Questions Wisdom of Open Borders — for Brazil

04/29/2018

Who would have thought that national sovereignty would get a plug from the Gray Lady — on its front page, no less.

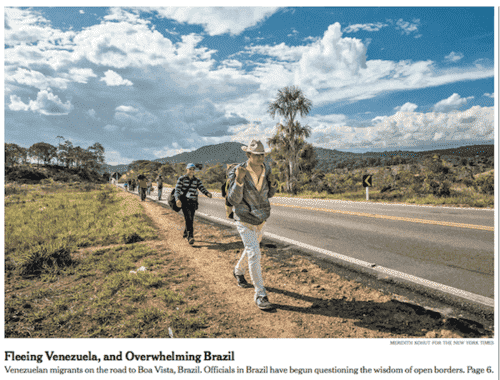

Sunday’s front page featured a photo of Venezuelans headed south to Brazil, where officials “have begun questioning the wisdom of open borders.”

The interior article reported on the turmoil created by thousands of Venezuelans fleeing socialism (without the word being mentioned) on nearby Brazil. Violent crime and drug dealing are up. Homeless, hungry foreigners crowd Brazilian streets, where they line up for free food distributed by the military. (Reuter reported in February that the average weight lost by Venezuelans last year was 24 pounds.) Communicable disease is a growing problem, along with lowered wages for all because of an excess of workers.

The symptoms may sound familiar to Americans.

It’s curious how the Times never considers that borders and sovereignty might be advantageous for the United States, particularly when millions of poor people south of the Rio Grande are determined to move here.

The Times article was reprinted by WRAL.com, so click away for the whole story:

Venezuela’s Turmoil Is Testing Brazil’s Limits, WRAL.com, By Ernesto Londono, New York Times, April 28, 2018

PACARAIMA, Brazil — Hundreds turn up each day, many arriving penniless and gaunt as they pass a tattered flag that signals they have reached the border.

Once they cross, many cram into public parks and plazas teeming with makeshift homeless shelters, raising concerns about drugs and crime. The lucky ones sleep in tents and line up for meals provided by soldiers — pregnant women, disabled people and families with young children are often given priority. The less fortunate huddle under tarps that crumple during rainstorms.

The scenes are reminiscent of the waves of desperate migrants who have escaped the wars in Syria and Afghanistan, spurring a backlash in Europe. Yet this is happening in Brazil, where a relentless tide of people fleeing the deepening economic crisis in Venezuela has begun to test the region’s tolerance for immigrants.

This month, the governor of the northern Brazilian state of Roraima sued the federal government, demanding it close the border with Venezuela and provide additional money for her overburdened education and health systems.

“We’re very fearful this may lead to an economic and social destabilization in our state,” said the governor, Suely Campos. “I’m looking after the needs of Venezuelans to the detriment of Brazilians.”

The tens of thousands of Venezuelans who have found refuge in Brazil in recent years are walking proof of a worsening humanitarian crisis that their government claims does not exist.

They also constitute an exodus that is straining the region’s largely generous and permissive immigration policies. Earlier this month, Trinidad deported more than 80 Venezuelan asylum-seekers. In Colombian and Brazilian border communities, local residents have attacked Venezuelans in camps.

During the early months of this year, 5,000 Venezuelans were leaving their homeland each day, according to the United Nations. At that rate, more Venezuelans are leaving home each month than the 125,000 Cuban exiles who fled their homes during the 1980 Mariel boat crisis and transformed South Florida.

If the current rate remains steady, more than 1.8 million Venezuelans could leave by the end of this year, joining the estimated 1.5 million who have fled the economic crisis to rebuild their lives abroad.

As Venezuelans began resettling across Latin America in large numbers in 2015, for the most part they found open borders and paths to legal residency in neighboring countries.

But as their numbers have swelled — and as a larger share of recent migrants arrive without savings and in need of medical care — some officials in the region have begun to question the wisdom of open borders.

Campos said she took the “extreme measure” of suing the federal government because the influx of Venezuelans led to a spike in crime, drove down wages for menial jobs and set off an outbreak of measles, which had been eradicated in Brazil.

At least 93 people were killed during the first four months of this year, already exceeding the 83 violent deaths recorded last year, Campos said. And law enforcement officials say drug trafficking in the region has increased as destitute Venezuelans have been drafted into Brazilian smuggling networks.

The population of Boa Vista, the state capital, ballooned over the past few years as some 50,000 Venezuelans resettled here. They now make up roughly 10 percent of the population. At first, residents responded with generosity, establishing soup kitchens and organizing clothes drives.

By last year however, local residents in Pacaraima, the border town, and Boa Vista, the state capital, which is 130 miles from the border, felt overwhelmed.

[ … ]

The U.N. recently asked international donors to donate $46 million to address the crisis during the remainder of this year, but so far it has secured only 6 percent of that goal. Mercedes Acuña, 50, said she felt blessed to have been among the first admitted into a shelter. She arrived in Brazil two months ago, rail thin, after an anguishing period during which she joined an ever-growing mob in the capital, Caracas, picking apart garbage for bits and pieces of discarded food.

Acuña said she had nothing but gratitude for the Brazilians who have helped her, but she has come to agree with those who say it’s time to shut the border.

“I realize we’re all in need,” she said. “But their country is being invaded.”