By Steve Sailer

10/23/2018

In The New Yorker’s increasingly frenzied pursuit of the Teen Vogue niche, we have a Donna Zuckerberg-style article:

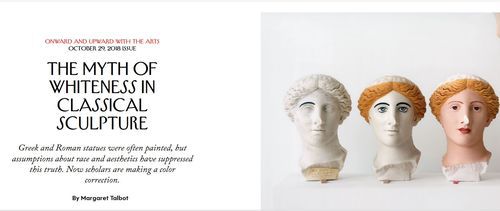

The Myth of Whiteness in Classical Sculpture

Greek and Roman statues were often painted, but assumptions about race and aesthetics have suppressed this truth. Now scholars are making a color correction.

By Margaret Talbot

Researchers demonstrate the process of applying color to the Treu Head, from a Roman sculpture of a goddess, made in the second century A.D. Ancient sculptures were often painted with vibrant hair colors and skin tones. Photograph by Mark Peckmezian for The New Yorker

See, ancient statues weren’t of whites, you racists, they were of gingers!

Mark Abbe was ambushed by color in 2000, while working on an archeological dig in the ancient Greek city of Aphrodisias, in present-day Turkey. At the time, he was a graduate student at New York University’s Institute of Fine Arts, and, like most people, he thought of Greek and Roman statues as objects of pure white marble. The gods, heroes, and nymphs displayed in museums look that way, as do neoclassical monuments and statuary, from the Jefferson Memorial to the Caesar perched outside his palace in Las Vegas.

… When Abbe arrived there, several decades later, he started poking around the depots and was astonished to find that many statues had flecks of color: red pigment on lips, black pigment on coils of hair, mirrorlike gilding on limbs.

My vague recollection is that this was reasonably well known in the 1970s, but I could be wrong about this.

What’s new about this is the emergence of the demon word “whiteness” into media abhorrence in the 2010s, allowing the press to declare an old controversy over aesthetics to be new proof that the Ancients were Diverse and modern white people are Racist for preferring ancient statues unadorned. After all, race doesn’t exist, except in the trivial sense of skin color, so you couldn’t possibly tell a subject’s race from facial features, right?

So, J.J. Winckelmann’s 18th Century exaltation of Greek sculptures as pure form wasn’t a big gay aesthetic breakthrough like everybody used to think. From Gay History & Literature:

Johann Joachim Winckelmann (1717-68) in his monumental History of Ancient Art established Greek art as the touchstone of all art irrespective of place or time. His ideal of beauty, which had a tremendous effect upon neoclassical artistic taste and art theory for more than a century, was grounded in his gay sensibility: “those who are observant of beauty only in women, and are moved little or not at all by the beauty of men, seldom have an impartial, vital, inborn instinct for beauty in art.”

Instead, Winckelmann was hypnotized by White Supremacy! (Wait, Winckelmann was a gay white suprematist? Is that a thing? It is? Uh oh … White = Bad, but Gay = Good. Does Not Compute. … Okay leave out the gay part about Winckelmann. Nobody will notice. Who remembers anything?)

… “You need to transform your eye into an objective tool in order to overcome this powerful imprint” — a tendency to equate whiteness with beauty, taste, and classical ideals, and to see color as alien, sensual, and garish. …

Lately, this obscure academic debate about ancient sculpture has taken on an unexpected moral and political urgency. Last year, a University of Iowa classics professor, Sarah Bond, published two essays, one in the online arts journal Hyperallergic and one in Forbes, arguing that it was time we all accepted that ancient sculpture was not pure white — and neither were the people of the ancient world. One false notion, she said, had reinforced the other. For classical scholars, it is a given that the Roman Empire — which, at its height, stretched from North Africa to Scotland — was ethnically diverse. In the Forbes essay, Bond notes, “Although Romans generally differentiated people on their cultural and ethnic background rather than the color of their skin, ancient sources do occasionally mention skin tone and artists tried to convey the color of their flesh.” Depictions of darker skin can be seen on ancient vases, in small terra-cotta figures, and in the Fayum portraits, a remarkable trove of naturalistic paintings from the imperial Roman province of Egypt, which are among the few paintings on wood that survive from that period. These near-life-size portraits, which were painted on funerary objects, present their subjects with an array of skin tones, from olive green to deep brown, testifying to a complex intermingling of Greek, Roman, and local Egyptian populations.

Not to mention little green men from Mars.

Bond told me that she’d been moved to write her essays when a racist group, Identity Evropa, started putting up posters on college campuses, including Iowa’s, that presented classical white marble statues as emblems of white nationalism. After the publication of her essays, she received a stream of hate messages online. She is not the only classicist who has been targeted by the so-called alt-right. Some white supremacists have been drawn to classical studies out of a desire to affirm what they imagine to be an unblemished lineage of white Western culture extending back to ancient Greece. When they are told that their understanding of classical history is flawed, they often get testy.

Earlier this year, the BBC and Netflix broadcast “Troy: Fall of a City,” a miniseries in which the Homeric hero Achilles is played by a British actor of Ghanaian descent. The casting decision elicited a backlash in right-wing publications. Online commenters insisted that the “real” Achilles was blond-haired and blue-eyed …. It’s true that Homer describes the hair of Achilles as xanthos, a word often used to characterize objects that we would call yellow, but Achilles is fictional

Thanks for clearing that up once and for all in just four words!

, so imaginative license in casting seems perfectly acceptable.

… In an essay for the online magazine Aeon, Tim Whitmarsh, a professor of Greek culture at the University of Cambridge, writes that the Greeks “would have been staggered” by the suggestion that they were “white.” Not only do our modern notions of race clash with the thinking of the ancient past; so do our terms for colors, as is clear to anyone who has tried to conceive what a “wine-dark sea” actually looked like. In the Odyssey, Whitmarsh points out, the goddess Athena is said to have restored Odysseus to godlike good looks in this way: “He became black-skinned again and the hairs became blue around his chin.” On the Web site Pharos, which was founded, last year, in part to counter white-supremacist interpretations of the ancient world, a recent essay notes, “Although there is a persistent, racist preference for lighter skin over darker skin in the contemporary world, the ancient Greeks considered darker skin” for men to be “more beautiful and a sign of physical and moral superiority.”

Thus, Clark Gable, with his year-round tan, had to stay in a hotel for blacks when he visited Jim Crow Atlanta for the 1939 premiere of Gone With the Wind. (And who can forget the memorable scene in that movie in which Scarlett’s last name is discovered to be O’Hara so she is immediately sold into slavery because the Irish weren’t white back then.)