By Steve Sailer

07/21/2012

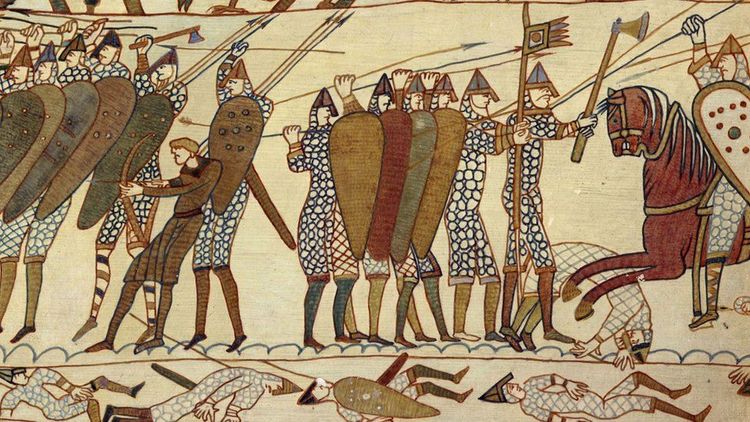

In Britain, there is still a small but measurable difference in social metrics between people on different sides of the Ivanhoe gap after nearly a millennium. From The Telegraph in 2011:

People with Norman names wealthier than other Britons

People with "Norman" surnames like Darcy and Mandeville are still wealthier than the general population 1,000 years after their descendants conquered Britain, according to a study into social progress.

Research shows that the descendants of people who in 1858 had "rich" surnames such as Percy and Glanville, indicating they were descended from the French nobility, are still substantially wealthier in 2011 than those with traditionally "poor" or artisanal surnames. Artisans are defined as skilled manual workers.

Drawing on data culled from official records that go back as far as the Domesday Book as well as university admissions and probate archives, Gregory Clark, a professor of economics at the University of California [at Davis], has tracked what became of people whose surnames indicated their ancestors had come from either the aristocratic or artisanal classes.

By studying the probate records of those with “rich” and “poor” surnames every decade since the 1850s, he found that the extreme differences in accumulated wealth narrowed over time.

But the value of the estates left by those belonging to the “rich” surname group, immortalised in the character of Fitzwilliam Darcy, in Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, were above the national average by at least 10 per cent.

In addition, today the holders of "rich" surnames live three years longer than average. Life expectancy is a strong indicator of socio-economic status.

Popular names of the medieval elite who were descended from Norman families include Balliol, Baskerville, Bruce, Darcy, Glanville, Lacy, Mandeville, and Venables.

Popular artisanal names that emerged in the 14th century include Smith, Carpenter, Mason, Shepherd, Cooper and Baker.

So, keep in mind that surnames typically didn’t get chosen until about a quarter of a century after 1066.

By the way, the kind of British surnames that show up on characters in a P.G. Wodehouse novel tend to be rare in America. The more upper crust sort of Brits didn’t emigrate to America much, except in the case of some younger sons. Here’s a list of Anglo-Norman names. Some are common here, such as Martin, but many are close to unknown in America, such as Curzon.

For example, here is a list of British Prime Ministers. Until the last century or so, there are lots of names like "Gascoyne-Cecil" (a.k.a., Salisbury) that you really wouldn’t expect to see on a U.S. President. Not many artisanal names like Thatcher. (Lately, though, it seems like an awful lot of Prime Ministers have Scottish names: David Cameron, Gordon Brown, Tony Blair, Alec Douglas-Home, and Harold Macmillan over the last half century.)

The Norman invasion is the reason we have pairs of words for living versus cooked animals — the commoners who raised animals spoke English, and the nobles who ate meat spoke Norman French. Thus we have cow/beef, calf/veal, sheep/mutton, swine/pork, deer/venison. (Wamba, the jester in Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe, catalogues these pairs.)